At first, Black men weren't allowed to fight for the Union Army during the Civil War, but by the end of the conflict, President Abraham Lincoln himself said that the war could not have been won without them.

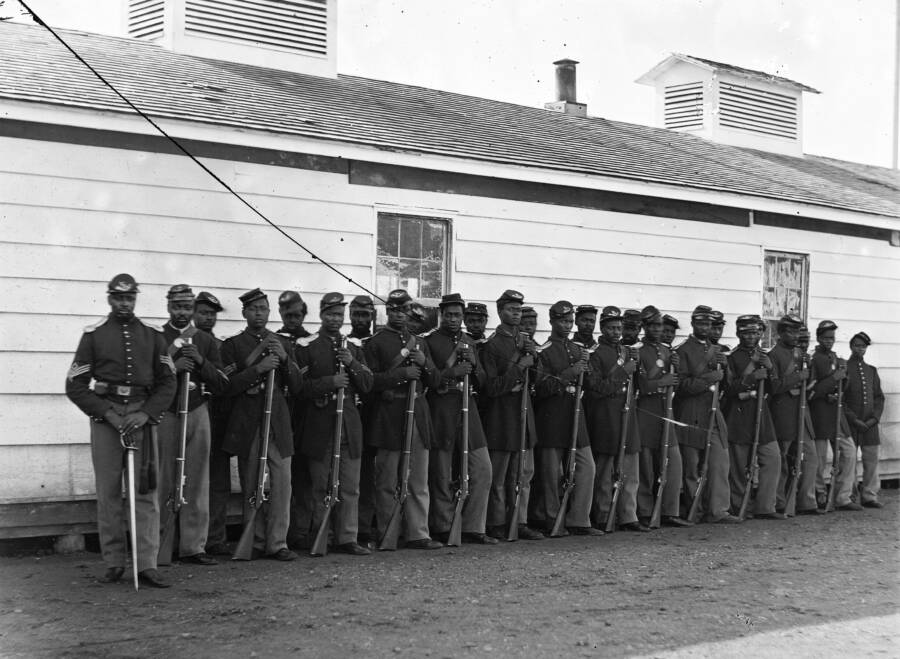

Public DomainBlack soldiers in the Fourth U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment, pictured at Fort Lincoln in Washington, D.C.

The American Civil War marked a major turning point in the history of the United States. Less than a century after it was officially founded, the U.S. was at risk of becoming two different countries, divided by fundamental ideological differences on slavery and abolition.

In the lead-up to Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, Southern states began to secede from the Union. Many in the South felt they had lost their political sway and feared what a federal abolition of slavery would do to their largely agricultural economy, so they formed the Confederacy.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, it illustrated just how large the divide between the North and the South had become. For the next four years, the United States was engaged in its bloodiest conflict, and following the First Battle of Bull Run and the Peninsula Campaign, many worried the war would end with a Confederate victory, as Union losses continued to mount.

After the Union forces had been depleted by 40 percent, Black men were finally permitted to join the Union Army in the summer of 1862. While some instantly jumped at the chance to join the fight in skirmishes, they weren’t officially recognized as part of the Union service until January 1863.

Then, on Jan. 1, 1863, Lincoln famously issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that “all persons held as slaves” in the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” But Lincoln’s proclamation didn’t end there. In it, he also called for freed slaves to enter “into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”

Until then, the Union had been hesitant to enlist Black Americans. The Lincoln administration worried that recruiting Black troops would lead more states to secede from the Union, further hurting their chances of winning the war. And some Union officers also wrongly believed that Black men weren’t brave enough or skilled enough to fight. In truth, the American Civil War’s Black soldiers helped solidify a victory for the Union.

33 Photos Of Black American Soldiers Who Fought In The Civil War — And The Untold History Behind Them

The First Black Soldiers Who Fought In The American Civil War

As the National Museum of the United States Army acknowledges, Black soldiers had served in America's military several times before the Civil War.

For example, the 1st Rhode Island Regiment was the first majority-Black regiment in American history, formed back in 1778, and during the War of 1812, Black soldiers helped defend New Orleans. Units in the volunteer Army were both segregated and integrated, but once that war was over, federal and state laws prohibited Black Americans from continued military service due to racism and worries about slave rebellions in the South.

After the Civil War broke out, many Union leaders were still uncertain whether to enlist Black Americans. But some saw an untapped opportunity.

By May 1861, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler had taken command of Union forces at Fort Monroe, Virginia, where he declared that escaped slaves who found his camp would be considered "contraband" of war — a loophole that allowed the men to fight alongside Butler's troops. Months later, more than 900 escaped slaves and their family members had arrived at Fort Monroe.

Butler was joined in his decision shortly thereafter by Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont in Missouri and Maj. Gen. David Hunter in South Carolina. Surprisingly, the Lincoln administration actually denounced the acts at the time, fearing losing the loyalty of pro-Union, slave-holding states.

Things started to change in 1862, however, as the war raged on and the Union forces eventually depleted by nearly 40 percent.

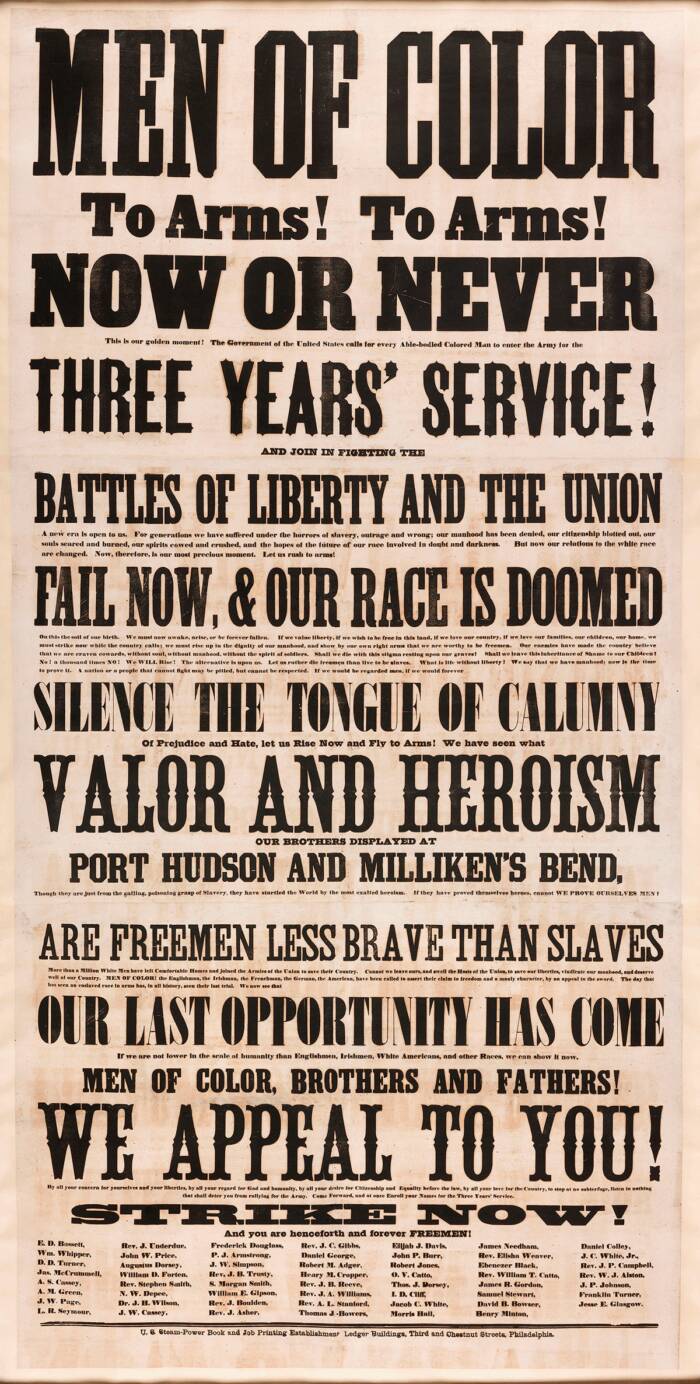

Public DomainA message penned by Frederick Douglass, calling on freed slaves and other Black Americans to enlist in the Union Army.

According to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, the number of white volunteers had dramatically dropped by mid-1862. Meanwhile, the number of escaped and former slaves continued to rise.

Sensing a shift in morale among white volunteers, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act, emancipating slaves who had been held by men in the Confederate Army or by supporters of the Confederacy. Then, the Militia Act of 1862 allowed "all able-bodied male citizens between ages of eighteen and forty-five" to join the Union Army. Though these were significant changes, they also limited Black soldiers to more menial roles, and these troops would also earn 30 percent less in pay than white soldiers.

Butler once again pushed further, raising several regiments of what he called the "Corps D'Afrique," which were among the first official U.S. Army regiments of color. The Union still suffered from morale issues, though, and this feeling continued after the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863.

In May of that same year, the New York Tribune described the general sentiment among Northern whites regarding the enlistment of Black soldiers: "Loyal Whites have generally become willing that they should fight, but the great majority have no faith that they will really do so. Many hope they will prove cowards and sneaks — others greatly fear it."

Weeks later, at Port Hudson, Louisiana, the United States Colored Troops (USCT) dispelled any concerns that they would not be able to fight.

How Black Soldiers Turned The Tide In Favor Of The Union Army

Although even the most experienced Black American soldiers had only been fighting in the Civil War, officially, for a few months at most, their courage and zeal proved to be major benefits for the Union Army.

Following the battle at Port Hudson in May 1863, Union general Nathaniel P. Banks reported of the Black regiments: "The severe test to which they were subjected, and the determined manner in which they encountered the enemy, leaves upon my mind no doubt of their ultimate success."

Less than a month later, in Milliken's Bend, Louisiana, USCT forces engaged in an intense battle against Confederate troops, fighting hand-to-hand with fists, bayonets, and rifle butts. Confederate Brigadier General Henry McCullough said his "charge was resisted by the Negro portion of the enemy's force with considerable obstinacy, while the white or true Yankee position ran like whipped curs almost as soon as the charge was ordered."

Black soldiers faced a harder fight than their white comrades, both against the Confederates and within the Union Army itself. If captured by the enemy, they were punished more severely than white soldiers and sometimes even sold into slavery. Discrimination and prejudice among the Northerners also prevented Black American soldiers from ascending to the highest ranks within their own regiments, and leadership of USCT forces was widely varied.

Still, some white soldiers acknowledged just how fundamental Black regiments were in securing victory for the Union.

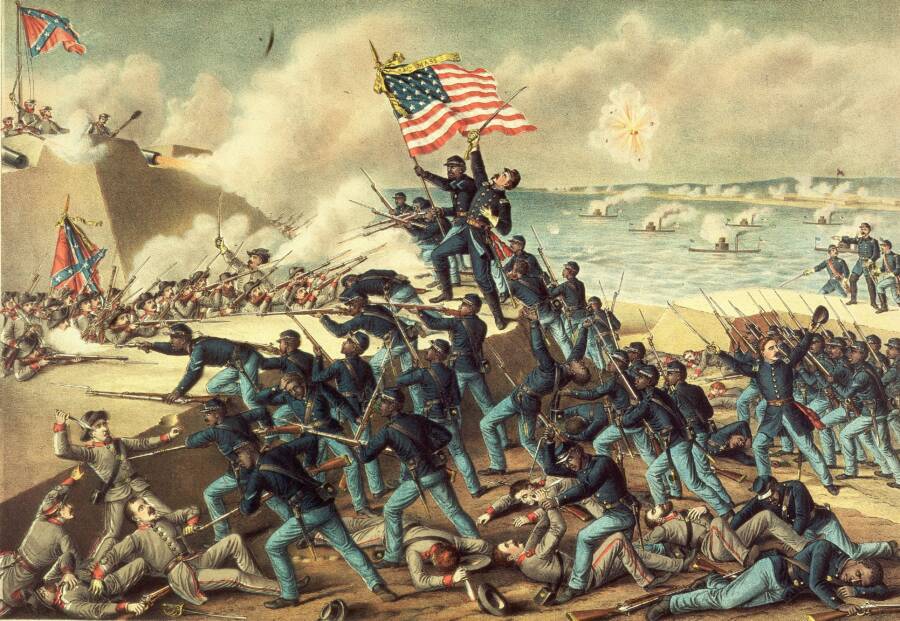

MPI/Getty ImagesAn illustration of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, one of the most famous regiments of Black soldiers who fought in the American Civil War, depicted during the July 1863 attack on Fort Wagner.

"No officer in this regiment now doubts that the key to the successful prosecution of this war lies in the unlimited employment of Black troops," wrote Col. T.W. Higginson of the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Regiment, after his Black soldiers carried out successful raids behind enemy lines along the St. Marys River, where a previous attempt with a white regiment had failed.

"It would have been madness to attempt [the battle], with the bravest white troops, what I have successfully accomplished with the Black ones."

By the end of the Civil War, approximately 180,000 Black soldiers had served in the Union Army, with another 19,000 serving in the Union Navy. Of those troops, about 90,000 were former slaves from the South. And though Black women could not officially join the Army as soldiers, many of them, such as Harriet Tubman, aided the Union effort as spies, nurses, and scouts.

"The North could not have won if not for the Black troops — the United States Colored Troops — because in addition to additional manpower, many of them were former slaves who had important intel," said historian and co-chair of the Juneteenth Legacy Project Sam Collins. "What is often forgotten is that those runaway slaves knew the Southern territory and landscape. So not only did they take their physical bodies when they ran away, hurting the labor force of the Southern plantations, they also took intel with them."

Abraham Lincoln likewise acknowledged the valuable contribution of the Civil War's Black soldiers: "Without the military help of the Black freedmen, the war against the South could not have been won."

After learning about how the American Civil War's Black soldiers helped secure victory for the Union Army, read the story of the Harlem Hellfighters, the often overlooked Black heroes of World War I. Or, read about the Buffalo Soldiers, the first all-Black peacetime regiments in U.S. history.