By Fritz von Burkersroda,

1 days ago

Sybil Ludington: The Teenage Patriot Who Outpaced Paul Revere

In 1777, a 16-year-old girl named Sybil Ludington rode 40 miles through the night to warn colonial militia of a British attack on Danbury, Connecticut—a distance twice as far as Paul Revere’s famous midnight ride. According to the traditional account, Ludington rode from her hometown in Fredericksburg, New York through Putnam County to rally approximately 400 militiamen under her father’s command. Her ride wasn’t easy—she rode through the dark, in the woods, and through rain, covering almost triple the length of Paul Revere’s famous ride just to make sure all were alerted of the British threat. However, modern historians have raised questions about the story’s accuracy, with relatively little contemporary evidence to support the account. Despite her heroic feat, Sybil was thanked by General George Washington himself, but unlike Paul Revere, whose name became universally known thanks to Longfellow’s poem, Sybil’s ride had been mostly forgotten by her death in 1839. In 1961, a bronze statue of her by renowned sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington was erected in Carmel, New York, finally giving this brave teenager the recognition she deserved.

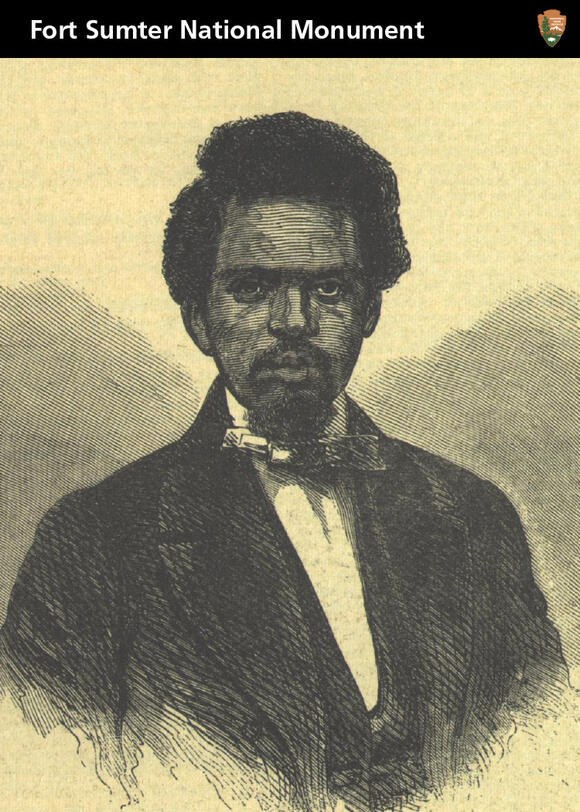

Robert Smalls: The Enslaved Man Who Stole a Confederate Ship

Robert Smalls was born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina in 1839, and during the Civil War, he commandeered a Confederate transport ship in Charleston Harbor and sailed it to Union forces. In the early hours of May 13, 1862, the 23-year-old enslaved man stood on the deck of the Confederate steamer Planter, knowing that in the next few hours, he and his young family would either find freedom or face certain death. Smalls and his crew picked up family members at a rendezvous point, then slowly navigated through the harbor, with Smalls doubling as captain and donning the captain’s wide-brimmed straw hat to help hide his face while responding with proper coded signals at Confederate checkpoints. Once outside Confederate waters, he had his crew raise a white flag and surrendered the ship to the blockading Union fleet, delivering 17 black passengers from slavery to freedom. His example helped convince President Abraham Lincoln to accept African-American soldiers into the Union Army, and after the war, Smalls became a politician, winning election to the South Carolina Legislature and the U.S. House of Representatives during Reconstruction. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1875 to 1879, from 1882 to 1883, and from 1884 to 1887.

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler: Pioneer of Medicine and Healing

Rebecca Lee Crumpler was the first Black woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. Born Rebecca Davis in Delaware in 1831, she was raised by an aunt in Pennsylvania who often helped care for sick neighbors, and those early experiences made her want to work to “relieve the suffering of others.” In 1860, Crumpler earned a place at the New England Female Medical College in Boston, which was the first school in the country to train women as doctors. On March 1, 1864, she received a “Doctress of Medicine” degree from the school at age 33. After earning her degree in Boston, she spent time in Richmond, Virginia after the Civil War, caring for formerly enslaved people, and in 1883, she published her “Book of Medical Discourses.” At the time Crumpler received her degree, there were 54,543 physicians in the country; 270 of them were women—all white—and 180 were African American men. She died of fibroid tumors on March 9, 1895, at age 64, and was buried in Fairview Cemetery without a headstone, but in 2020, 125 years after her death, a proper headstone was finally installed.

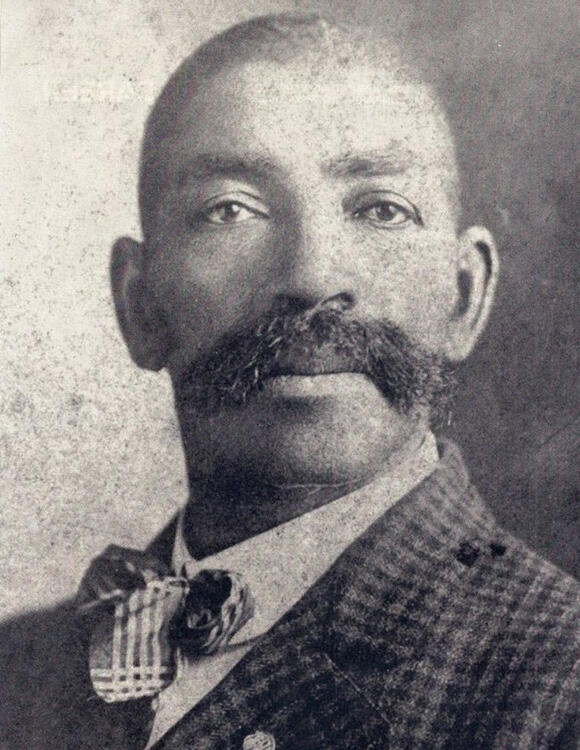

Bass Reeves: The Real-Life Lone Ranger

Born to slave parents, Bass Reeves would become the first black U.S. Deputy Marshal west of the Mississippi River and a great frontier hero. In 1875, he was commissioned as a deputy U.S. marshal by Federal Judge Isaac Parker, responsible for apprehending criminals in a 75,000-square-mile region of what is now mostly Oklahoma and Arkansas. Well known for his valor, Reeves killed 14 outlaws and apprehended more than 3,000 throughout his 32-year tenure, including his own son. An imposing figure always riding a large white stallion, Reeves was usually a spiffy dresser with polished boots and was known for his politeness and courteous manner. However, when the purpose served him, he was a master of disguises, sometimes appearing as a cowboy, farmer, or outlaw himself, always wearing two Colt pistols butt forward for a fast draw, and being ambidextrous, he rarely missed his mark. Many argue that there is evidence Bass Reeves was the basis for the classic “Lone Ranger” character, with several key similarities between the fictional character and the actual legend.

Mary Edwards Walker: The Only Woman to Receive the Medal of Honor

Mary Edwards Walker was an American abolitionist, prohibitionist, prisoner of war, and surgeon during the Civil War, and she remains the only woman to receive the Medal of Honor. Walker graduated with a medical degree from Syracuse Medical College in 1855, married her fellow medical student Albert Miller, and they set up a joint practice in Rome, New York, though it failed because the public wouldn’t accept a female doctor. When the Civil War began in 1861, Walker wanted to join the Union’s efforts, but was not allowed to serve as a medical officer because she was a woman, so she decided to serve as an unpaid volunteer surgeon at the U.S. Patent Office Hospital in Washington. In 1863, her request to practice as a surgeon was finally accepted, and she became the first female U.S. Army surgeon as a “Contract Acting Assistant Surgeon.” While serving, she routinely crossed enemy lines to treat civilians, and in 1864, she was detained by Confederate troops and arrested for spying, spending four months at the notorious Castle Thunder prison near Richmond, Virginia. Based on recommendations from Major Generals Sherman and Thomas, President Andrew Johnson presented her with the Medal of Honor in 1865, though it was stripped in 1917 and restored in 1977—she remains the only woman to receive this honor.

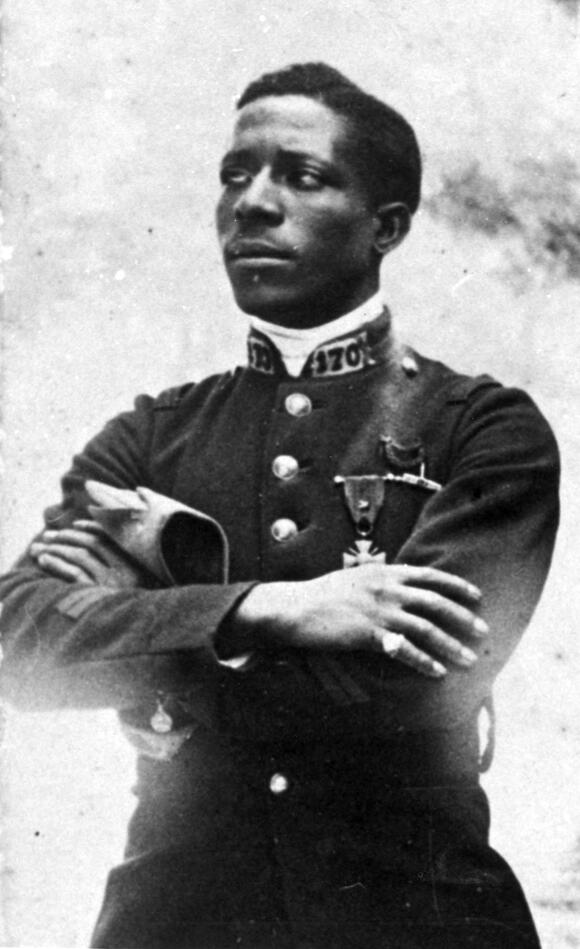

Eugene Bullard: America’s First Black Fighter Pilot

Eugene Bullard became the first Black American fighter pilot during World War I, though he had to fly for France rather than his own country. Born in Georgia in 1895, Bullard left the United States as a teenager, fleeing the racism and violence of the Jim Crow South. He made his way to France, where he found opportunities that were denied to him in America. When World War I broke out, Bullard enlisted in the French Foreign Legion and fought in the trenches before transferring to the French Air Service. As a pilot with the Lafayette Flying Corps, he flew combat missions over the Western Front, earning the nickname “The Black Swallow of Death.” Despite his heroic service and combat experience, the U.S. military refused to accept Black pilots when America entered the war. Bullard’s achievements were largely forgotten until decades later, when historians began recognizing his pioneering role in military aviation. His story represents both the courage of early aviators and the tragic loss of talent due to America’s racial prejudices.

Grace Hopper: The Admiral Who Revolutionized Computing

Grace Hopper was a Navy rear admiral and computer science pioneer who helped develop COBOL programming language and popularized the term “debugging.” Born in 1906, she earned a PhD in mathematics from Yale University in 1934, making her one of the first women to achieve this distinction. During World War II, she joined the Navy WAVES and was assigned to work on the Harvard Mark I computer, one of the first programmable computers in America. Her work on early computers led to groundbreaking innovations in programming languages that made computers more accessible to everyday users. Hopper believed that programming languages should be written in English rather than mathematical symbols, a revolutionary idea that led to the development of COBOL. She coined the term “debugging” after her team found an actual moth stuck in a computer relay. Throughout her career, she championed the idea that computers should be user-friendly and accessible to non-mathematicians. Her contributions to computer science were so significant that she’s often called the “Mother of Computing,” yet her name remains relatively unknown compared to her male counterparts.

Claudette Colvin: The Teenager Who Sparked a Movement

Nine months before Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat, a 15-year-old girl named Claudette Colvin made the same brave stand in Montgomery, Alabama. On March 2, 1955, Colvin was riding the bus home from school when the driver ordered her to give up her seat to a white passenger. She refused, declaring that it was her constitutional right to sit there. Police were called, and Colvin was arrested and charged with violating segregation laws, disorderly conduct, and assault. Her courage that day helped inspire the Montgomery Bus Boycott, though she was largely overlooked by civil rights leaders who felt that a pregnant teenager would not be the ideal symbol for their cause. Colvin’s story demonstrates how young people have often been at the forefront of social change, even when their contributions go unrecognized. She continued to fight for civil rights throughout her life, eventually becoming a nurse’s aide and raising her family in the Bronx. Despite being overshadowed by Rosa Parks, Colvin’s act of defiance was equally important in challenging the unjust laws of segregation.

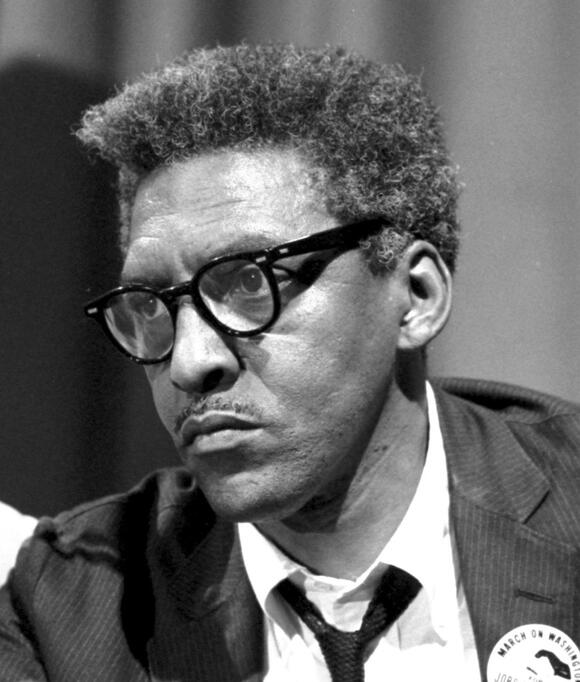

Bayard Rustin: The Architect of the March on Washington

Bayard Rustin was the chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, one of the most important events in the civil rights movement, yet he was often kept in the shadows due to his sexuality. Born in 1912, Rustin was a brilliant strategist and advocate for nonviolent resistance who helped mentor Martin Luther King Jr. in the principles of peaceful protest. He had extensive experience in organizing mass demonstrations and was instrumental in planning the logistics of the March on Washington, from securing permits to coordinating with labor unions and religious groups. Despite his crucial role, other civil rights leaders were concerned that Rustin’s homosexuality and past association with communist organizations would be used to discredit the movement. As a result, he was often forced to work behind the scenes, receiving little public recognition for his contributions. Rustin’s story highlights the complex dynamics within the civil rights movement and the additional challenges faced by those who belonged to multiple marginalized groups. His strategic genius and dedication to nonviolence were essential to the success of the civil rights movement, yet his name is rarely mentioned in history books.

Dr. Charles Drew: The Blood Bank Pioneer

Dr. Charles Drew was a Black surgeon who pioneered blood plasma storage techniques that saved countless lives during World War II, yet he faced tragic irony in his own death. Born in 1904, Drew became fascinated with blood transfusions during his medical studies and went on to earn a doctorate in medicine from Columbia University. His research on blood preservation and storage revolutionized military medicine, as his techniques allowed blood plasma to be stored for weeks rather than days. During WWII, Drew directed the American Red Cross blood donor program and established blood banks that supplied plasma to British forces. His innovations were so successful that they became the standard for blood storage worldwide. Despite his life-saving work, Drew faced constant racial discrimination throughout his career, being denied positions at white hospitals and medical schools. The tragic irony of his story is that he died in 1950 after a car accident, and according to some accounts, he was denied treatment at a whites-only hospital. While this particular detail has been disputed by historians, it symbolizes the bitter reality of racism in American medicine during Drew’s era.

The Navajo Code Talkers: Unbreakable Warriors

The Navajo Code Talkers were Native American Marines who developed an unbreakable code based on the Navajo language that proved crucial to Allied victories in the Pacific during World War II. Recruited from Navajo communities in the Southwest, these young men created a military code that stumped Japanese codebreakers throughout the war. The code was based on the complex Navajo language, which was unwritten and known to fewer than 30 non-Navajo people at the time. The Code Talkers translated military terms into Navajo, often using nature-based metaphors that made the code even more difficult to crack. They served in every major Pacific battle, from Guadalcanal to Iwo Jima, transmitting vital tactical information that helped coordinate military operations. The irony of their service was profound—many of these young men had been punished for speaking their native language in government boarding schools, yet their language became their greatest contribution to the war effort. Their code was so successful that it remained classified for decades after the war, and the Code Talkers were sworn to secrecy. It wasn’t until 1968 that their story was declassified, and they finally received the recognition they deserved for their unique contribution to Allied victory.

Shirley Chisholm: Unbought and Unbossed

Shirley Chisholm made history as the first Black woman elected to Congress and the first to seek the Democratic nomination for president, running on the slogan “Unbought and Unbossed.” Born in 1924, Chisholm grew up in Brooklyn and worked as a teacher before entering politics. In 1968, she was elected to represent New York’s 12th congressional district, becoming the first African American woman in Congress. Her maiden speech in the House was a powerful critique of the Vietnam War, arguing that money spent on the war should instead be used to address poverty and inequality at home. In 1972, she launched a groundbreaking campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination, facing both racial and gender discrimination from her own party. Despite receiving death threats and being excluded from televised debates, Chisholm persevered and won several primaries, proving that a Black woman could be a serious contender for the highest office in the land. Throughout her career, she was a fierce advocate for civil rights, women’s rights, and social justice, often taking positions that put her at odds with both Democratic and Republican establishments. Her legacy as a trailblazer continues to inspire politicians today, showing that courage and principle can overcome even the most entrenched barriers.

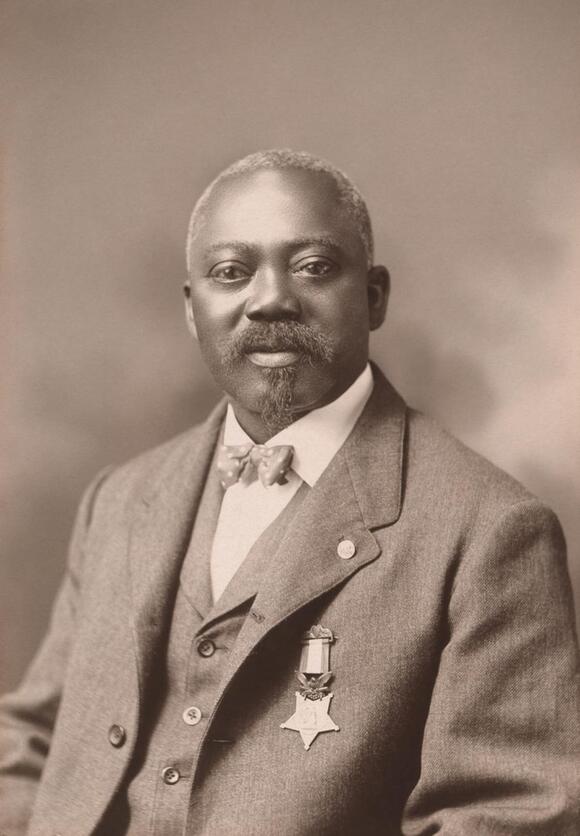

Sergeant William Carney: The Flag Bearer of Fort Wagner

Sergeant William Harvey Carney became the first Black recipient of the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions during the Civil War Battle of Fort Wagner in 1863. Born into slavery around 1840, Carney escaped to freedom and enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the first African American units to serve in the Union Army. During the assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina, Carney’s unit faced devastating fire from Confederate forces, and many soldiers fell, including the color bearer carrying the American flag. Seeing the flag about to touch the ground, Carney grabbed it and continued forward despite being wounded multiple times. He planted the flag on the fort’s parapet and held it there until forced to retreat with his unit. Despite being shot in the face, shoulder, arm, and leg, Carney refused to let the flag fall, declaring to his fellow soldiers, “Boys, I only did my duty; the old flag never touched the ground!” His courage under fire exemplified the dedication of Black soldiers who fought not just for the Union, but for their own freedom and dignity. Although he performed this heroic act in 1863, Carney didn’t receive the Medal of Honor until 1900, nearly four decades later, reflecting the discrimination that delayed recognition of Black soldiers’ contributions.

Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey: The FDA Scientist Who Saved America

Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey was an FDA scientist whose refusal to approve thalidomide in the United States prevented thousands of birth defects and changed drug regulation forever. Born in Canada in 1914, Kelsey earned her medical degree and doctorate in pharmacology before joining the FDA in 1960. One of her first assignments was to review an application for thalidomide, a sedative that was being marketed as safe for pregnant women. Despite pressure from the pharmaceutical company, Kelsey demanded more safety data, noting that the drug had not been adequately tested on pregnant women. Her persistence and scientific rigor proved lifesaving when reports