In the closing months of World War II, the protections outlined in the Geneva Convention were not always honored. In newly occupied parts of Germany, surrendered soldiers were deliberately denied official prisoner-of-war status. Instead, the Allies classified them differently, a move that allowed them to sidestep many of the legal and humanitarian requirements normally applied to POWs.

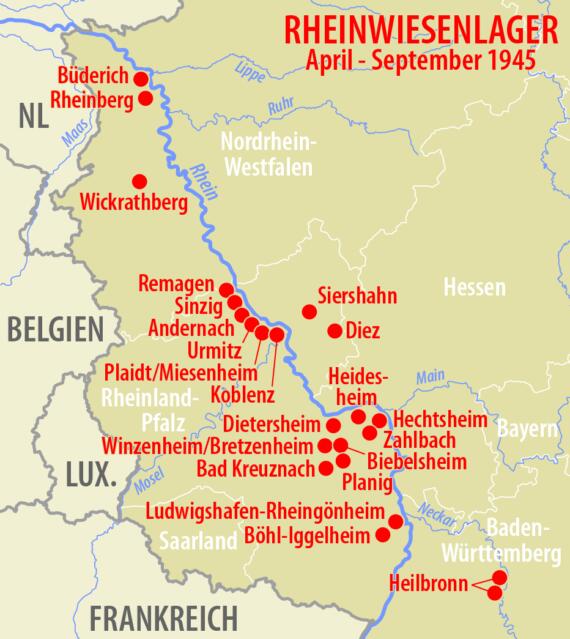

This decision led to the creation of vast detention sites across western Germany. Known as the Rheinwiesenlager, or Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosures (PWTE), these makeshift camps confined hundreds of thousands of German troops. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, and limited supplies made conditions harsh, especially as the war ground to an end.

Despite their scale and significance, the Rheinwiesenlager remain a largely overlooked chapter of the postwar story.

Allied success in Europe following the D-Day landings

After the success of D-Day, Allied forces pushed through occupied areas and into Germany. Although they met some resistance, many German soldiers surrendered, and the Allies became responsible for housing and caring for them.

At first, both British and American forces shared this responsibility. But by early 1945, the British refused to accept new prisoners due to limited space in their camps. This left the Americans with the full responsibility of handling the increasing number of POWs as the war continued.

To manage the growing number of captives, the U.S. Army set up the Rheinwiesenlager—a group of prison camps located throughout Allied-occupied Germany. These camps began operating in April 1945 and became even more important after Germany's surrender in May, helping prevent any possible uprisings during the early days of the occupation.

Layout of the Rheinwiesenlager

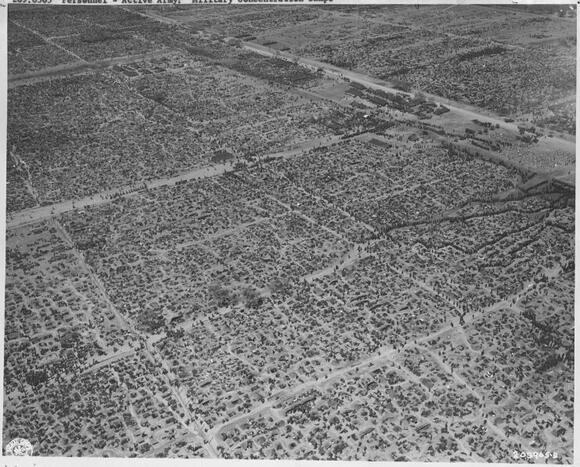

The Rheinwiesenlager camps were set up on farmland in western Germany under Allied control, strategically located near rail lines to streamline the transport of prisoners. Enclosed by barbed wire, each camp was subdivided into sections meant to accommodate 5,000-10,000 people. However, the number of detainees quickly exceeded those limits, with some camps swelling to over 100,000 prisoners. In total, it's estimated that between 1 and 1.9 million people passed through the Rheinwiesenlager system.

The vast majority of those held were ordinary Wehrmacht soldiers who had surrendered as the war came to a close. In contrast, high-ranking officers, members of the SS , and other notable individuals were usually removed from these camps and transferred elsewhere for interrogation, prosecution, or further investigation.

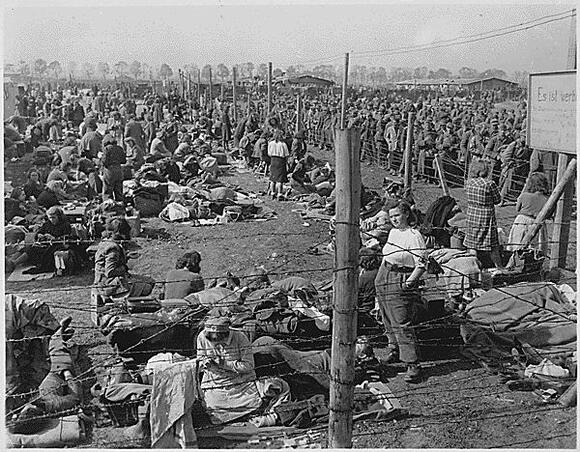

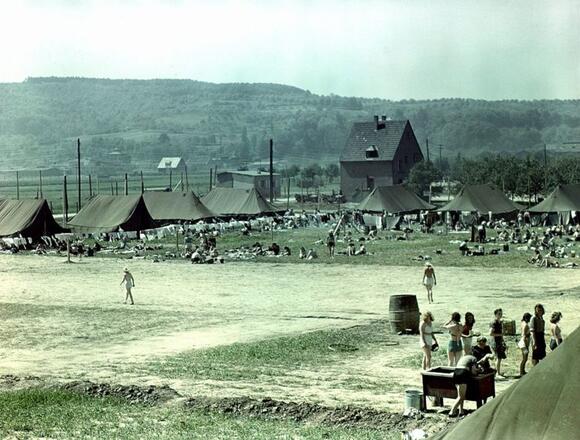

There were no shelters for living quarters

Within the Rheinwiesenlager camps, the responsibility for day-to-day survival largely rested on the prisoners themselves. With little direct supervision, they formed labor groups, tended to the ill and injured, and rationed the meager supplies of food. A handful of men were tasked with enforcing rules and maintaining order among their peers, a duty that sometimes came with the modest privilege of extra portions. Though the camps had designated areas for cooking, medical care, and administration, these sections were off-limits as living quarters. Most detainees were forced to fashion their own shelters, either by digging into the soil or piecing together crude coverings from scraps at hand. Exposed to the weather and deprived of basic comforts, life in the camps required both endurance and constant ingenuity.

Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs)

The harsh conditions faced by these prisoners, reflected in their crude outdoor shelters, highlighted the severe treatment they received from their captors. This treatment was allowed because they were designated as Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs) rather than prisoners of war (POWs).

Before the Rheinwiesenlager camps were created, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower introduced this new classification, stripping away the protections guaranteed to POWs under the Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War (1929). American forces defended this decision by asserting that these individuals belonged to a state that no longer existed, thereby justifying alternative forms of mistreatment.

Was the inhumane treatment intentional?

Under this classification, authorities could "legally" block Red Cross visits and withhold humanitarian aid. The Geneva Convention was specifically designed to prevent the abuse of POWs, but without its protections, DEFs were exposed to mistreatment with little accountability for their captors.

These events have led many to view the actions of Eisenhower and those in charge of the Rheinwiesenlager as intentional acts of inhumane treatment.

Rheinwiesenlager conditions

Overall, the conditions in the Rheinwiesenlager were horrific.

Historian Stephen Ambrose investigated many claims made about the camps, and concluded, "Men were beaten, denied water, forced to live in open camps without shelter, given inadequate food rations and inadequate medical care. Their mail was withheld. In some cases prisoners made a 'soup' of water and grass in order to deal with their hunger."

Begging for more food wasn't an option either, as those prisoners were often shot as "escapees," should they have gotten near the barbed wire fences. Reports also claim locals would be shot if they tried to provide aid to the POWs.

Legacy of the Rheinwiesenlager

Given the living conditions of the Disarmed Enemy Forces, it's no wonder the death toll was high. However, because they weren't officially known as prisoners of war, few records were kept. Instead, many Germans would simply go missing from roll call, never to be seen again.

Due to the lack of records, death estimates vary, depending on who you ask. The official statistics from the US Army state that around 3,000 people died while in the Rheinwiesenlager. German estimates, however, provide a figure of 4,537.

James Bacque, the author of Other Losses: An Investigation Into the Mass Deaths of German Prisoners at the Hands of the French and Americans After World War II, alleges the number is between 100,000 and one million. However, his claims have been discredited by his peers.

More from us:The Battle of Cologne Saw a Legendary Standoff Between a Panther and a Pershing

Regardless of the overall death toll, the treatment of DEFs has been heavily criticized, despite it going largely unnoticed in more recent years. Many have pointed out that the Americans violated a host of international laws on the treatment of prisoners, even though they weren't classified as POWs, particularly in their feeding - or lack thereof.p