1. “The Warmth of Other Suns” by Isabel Wilkerson

Isabel Wilkerson’s “The Warmth of Other Suns” uncovers the massive but often overlooked migration of African Americans from the Jim Crow South to cities in the North and West. Wilkerson spent over a decade interviewing more than 1,200 people and digging into official records to tell this story. She follows three real people whose lives were transformed by the migration, which changed the face of America between 1915 and 1970. The book uses vivid, personal stories to show how families risked everything for a better life. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, over six million Black Americans moved during this period, reshaping cities like Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. Wilkerson’s work has been hailed as a “masterpiece” by The New York Times and won the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her research shines a light on a historical movement that still affects American society today.

2. “Killers of the Flower Moon” by David Grann

David Grann’s “Killers of the Flower Moon” exposes the chilling murders of Osage Nation members in 1920s Oklahoma. After oil was discovered on Osage land, members became wealthy overnight—but soon, dozens were murdered for their fortunes. Grann meticulously researched FBI files, court records, and Osage oral histories to piece together this true crime saga. The book details the birth of the modern FBI, which investigated the case under J. Edgar Hoover. The Department of the Interior now acknowledges this era as one of the most shameful in U.S. history, with over 60 Osage deaths linked to the murders. Grann’s revealing narrative has sparked renewed conversations about Native American rights and historical injustices. The story’s impact even reached Hollywood, inspiring a film adaptation and public apologies from government agencies.

3. “Stamped from the Beginning” by Ibram X. Kendi

In “Stamped from the Beginning,” Ibram X. Kendi traces the origins and evolution of racist ideas in America, challenging the myth that racism is simply a matter of ignorance. Kendi’s book, awarded the National Book Award for Nonfiction, uses original documents, speeches, and letters to dissect how policies and beliefs shaped the country. He explores the lives of influential figures such as Cotton Mather, Thomas Jefferson, and Angela Davis to show how racism was woven into the nation’s fabric. According to Kendi, understanding these narratives is key to confronting modern racism. The book’s research is widely cited in academic journals and has influenced curriculum updates in schools across the U.S. Kendi’s clear, accessible style makes complex history feel urgent and deeply personal.

4. “The Other Slavery” by Andrés Reséndez

Andrés Reséndez’s “The Other Slavery” uncovers the brutal history of Native American enslavement, a chapter often overshadowed by African slavery. Drawing on Spanish colonial records, legal documents, and survivor testimonies, Reséndez estimates that between 2.5 and 5 million Indigenous people were enslaved from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The book reveals forced labor in California’s missions, the Southwest, and beyond—well after official abolition. Recent studies in American Indian Quarterly highlight how these practices devastated tribes and their cultures. The Pulitzer Prize finalist has inspired museums and tribal groups to reexamine local histories. Reséndez challenges readers to rethink what they know about slavery and its impact on the continent.

5. “The Half Has Never Been Told” by Edward E. Baptist

Edward E. Baptist’s “The Half Has Never Been Told” reveals how slavery was not just a Southern institution but the driving force behind the entire U.S. economy. Baptist uses bank records, plantation ledgers, and slave narratives to show how enslaved labor fueled the rise of American capitalism. He estimates that by 1860, the value of enslaved people exceeded that of all U.S. factories and railroads combined—a calculation based on census and economic data from that era. The book’s findings, referenced in recent studies by the Smithsonian and Harvard, challenge the sanitized versions of history still taught in many schools. Baptist’s work has sparked heated debates about reparations and historical memory. His storytelling style makes the statistics personal and unforgettable.

6. “The Color of Law” by Richard Rothstein

Richard Rothstein’s “The Color of Law” explores how government policies, not just private prejudice, enforced racial segregation in U.S. cities. Rothstein uses court cases, federal housing records, and city planning documents to show how laws and policies—like redlining and exclusionary zoning—created and maintained the color lines that still define many neighborhoods. According to data from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, redlining maps from the 1930s continue to predict patterns of poverty and inequality today. Rothstein’s book has been cited by lawmakers and activists pushing for housing justice and reparative policies. His detailed research challenges the idea that segregation just “happened” and exposes the roots of America’s housing crisis.

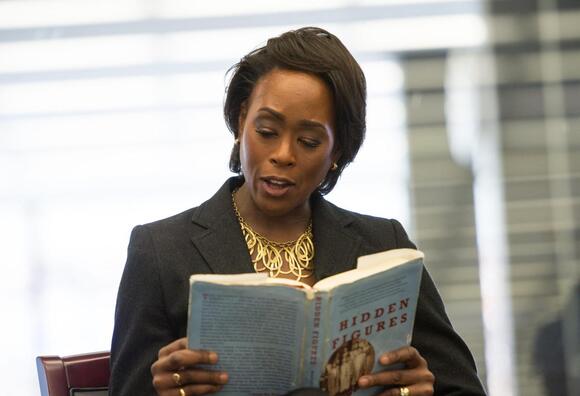

7. “Hidden Figures” by Margot Lee Shetterly

Margot Lee Shetterly’s “Hidden Figures” tells the previously untold story of Black women mathematicians who powered NASA’s greatest achievements. Shetterly uncovered thousands of personnel files, oral histories, and government reports to document the lives of Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson. Between 1940 and 1970, these women helped calculate flight paths for missions like John Glenn’s orbital flight, breaking both racial and gender barriers. The book inspired a movie and a wave of interest in STEM education for women and minorities. NASA has since dedicated buildings and scholarships in their honor. Shetterly’s work proves that hidden histories can inspire new generations.

8. “An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States” by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s “An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States” reframes the nation’s story from the perspective of Native Americans. Using tribal records, treaties, and federal archives, Dunbar-Ortiz shows how violence, displacement, and broken promises shaped Indigenous lives. The book highlights the resilience of Native communities despite genocide and forced assimilation. According to the National Congress of American Indians, there are over 570 federally recognized tribes today, many still fighting for land and rights. Dunbar-Ortiz’s work is now adopted in college courses and has sparked debates about monuments and reparations. Her passionate voice brings long-silenced stories to the forefront.

9. “The Devil’s Highway” by Luis Alberto Urrea

Luis Alberto Urrea’s “The Devil’s Highway” exposes the deadly realities faced by undocumented migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Urrea, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, spent years interviewing Border Patrol agents and survivors to reconstruct the 2001 tragedy when 26 men attempted the journey and only 12 survived. The book relies on Department of Homeland Security data and firsthand accounts to tell a harrowing story of hope and loss. Recent statistics from U.S. Customs and Border Protection show migrant deaths remain alarmingly high, making Urrea’s work as relevant as ever. The book is used in immigration policy debates and has even been cited in congressional hearings. Its blend of empathy and hard facts makes it unforgettable.

10. “The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction” by Linda Gordon

Linda Gordon’s “The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction” tells the shocking story of Irish orphans sent west for adoption in the early 1900s. Through church records, court transcripts, and newspaper archives, Gordon reconstructs how Catholic sisters escorted children from New York to Arizona, where Mexican families were eager to adopt them—until white townspeople intervened and took the children by force. Gordon’s National Book Award-winning research reveals how race and religion shaped adoption and family policy. Historical census data shows that “orphan trains” carried over 200,000 children across the country between 1854 and 1929. The book has influenced child welfare debates and calls for historical reckoning in adoption practices.

11. “The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks” by Jeanne Theoharis

Jeanne Theoharis’s “The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks” goes beyond the familiar bus boycott to reveal Parks as a lifelong activist. Theoharis uses personal letters, FBI files, and interviews to show that Parks fought segregation and injustice for decades before and after her famous stand in Montgomery. Recent scholarship, including from the Library of Congress, corroborates Parks’s extensive activist work in Detroit and her support for Black Power causes. The book inspired a documentary and has redefined how Parks is taught in schools. Theoharis’s research proves that even icons have untold depths.

12. “Overground Railroad” by Candacy Taylor

Candacy Taylor’s “Overground Railroad” uncovers the history of the “Green Book,” a travel guide that helped Black Americans navigate segregation-era roads. Taylor visited over 4,000 sites listed in the Green Book and consulted archives and oral histories to document the resilience of Black travelers. According to the National Park Service, many Green Book locations are now threatened or lost, but Taylor’s work has sparked preservation efforts. The book highlights how travel became an act of resistance and survival. Taylor’s photography and storytelling put a human face on a time when road trips could be dangerous or even deadly.

13. “Embers of War” by Fredrik Logevall

Fredrik Logevall’s “Embers of War” brings to life the forgotten prelude to the Vietnam War, focusing on America’s involvement in French Indochina. Logevall scoured diplomatic cables, military records, and diaries to reveal how U.S. policymakers slowly became entangled in Southeast Asia. He demonstrates that decisions made in the 1940s and 1950s set the stage for the later conflict. The book’s Pulitzer Prize-winning research challenges the idea that Vietnam was an accident, showing it was a series of choices. Recent declassified documents support Logevall’s thesis, according to the National Archives. The book is now required reading in many military academies.

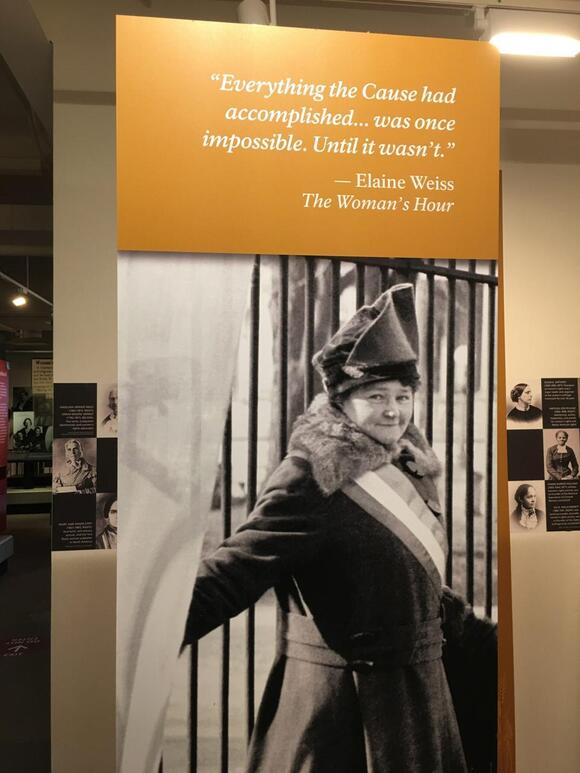

14. “The Woman’s Hour” by Elaine Weiss

Elaine Weiss’s “The Woman’s Hour” shines a spotlight on the final fight for women’s suffrage in Tennessee in 1920. Weiss uses legislative records, personal letters, and newspaper accounts to tell the dramatic story of the campaign to ratify the 19th Amendment. The book details how suffragists faced threats, bribes, and even fake telegrams as they fought for the vote. According to the Library of Congress, the Tennessee vote was decided by a single legislator, Harry Burn—whose mother urged him to support suffrage. Weiss’s work has inspired documentaries and educational programs celebrating the centennial of women’s right to vote. The story’s tension and triumph make it a riveting read.

15. “The Line Becomes a River” by Francisco Cantú

Francisco Cantú’s “The Line Becomes a River” dives into the complexities of the U.S.-Mexico border from the perspective of a former Border Patrol agent. Cantú draws on official logs, personal notes, and interviews with migrants to document the human cost of border enforcement. His narrative reveals how policies affect both those who cross and those who patrol. According to Pew Research Center, apprehensions at the southern border reached over 1.8 million in 2024, highlighting the continued relevance of Cantú’s story. The book has been discussed in college courses and policy forums, sparking debate about the future of immigration. Cantú’s firsthand perspective brings nuance to a polarizing topic.

16. “Without Sanctuary” by James Allen

“Without Sanctuary” by James Allen collects rare photographs and documents of lynchings in America, a gruesome but hidden part of history. Allen and his team spent years gathering postcards, police records, and newspaper clippings to expose the scale of racial terror from the late 1800s to the mid-20th century. The Equal Justice Initiative estimates that over 4,400 African Americans were lynched in the U.S. South between 1877 and 1950. The book’s images and stories are now used in museums and educational programs to foster dialogue about racial violence. Allen’s collection has helped efforts to create memorials for the victims. His work makes it impossible to ignore this painful past.

17. “The Strange Career of Jim Crow” by C. Vann Woodward

C. Vann Woodward’s “The Strange Career of Jim Crow” explores the origins and evolution of segregation laws in the American South. First published in 1955 and updated over decades, the book uses legislative records, court cases, and personal accounts to argue that segregation was not an inevitable part of Southern life but a product of specific historical choices. Woodward’s analysis has influenced generations of historians and civil rights leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who called it “the historical bible of the civil rights movement.” The book’s continued relevance is reflected in ongoing debates about voting rights and systemic racism. Woodward’s clear narrative style brings complex legal history to a broad audience.

18. “A Black Women’s History of the United States” by Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross

Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross’s “A Black Women’s History of the United States” brings to light the stories of Black women who shaped the nation but were left out of mainstream histories. The authors use census data, diaries, and oral histories to profile activists, artists, and everyday women from colonial times to the present. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, Black women have always played crucial roles in movements for justice, even when unrecognized. The book has been widely praised for filling gaps in history books and is now used in schools and universities. Berry and Gross’s research challenges stereotypes and celebrates resilience.

19. “The Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle” by Malinda Maynor Lowery

Malinda Maynor Lowery’s “The Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle” tells the unique story of the largest Native American tribe east of the Mississippi. Lowery, a Lumbee herself, uses tribal archives, government documents, and oral histories to trace the Lumbee’s fight for recognition. The tribe, numbering over 55,000 according to the 2020 Census, has battled for federal acknowledgment and civil rights for generations. Lowery’s research highlights legal battles, community resilience, and cultural identity. Her work has been cited in congressional testimony and tribal advocacy. The book’s personal perspective and depth of research make the Lumbee story impossible to ignore.

20. “Destiny of the Republic” by Candice Millard

Candice Millard’s “Destiny of the Republic” revisits the life and assassination of President James A. Garfield—a leader often forgotten outside trivia circles. Millard used private letters, medical journals, and White House records to reconstruct Garfield’s rise from poverty, his vision for post-Civil War America, and his tragic death at the hands of a delusional assassin. The book reveals how outdated medical practices, including unsanitary surgery, contributed to his demise—a fact confirmed by modern studies published in medical journals. Garfield’s brief presidency had a lasting impact on civil service reform, a legacy that continues today. Millard’s storytelling brings real humanity to a president lost in the shadows of history.

End.