Activism / September 11, 2025

How Arkansas’s secretive plan for a new state lockup angered people in a deep red corner of rural America—and changed how some see incarceration.

In Arkansas, a Small Community Fights the Nation’s Next Mega Prison

A secretive plan for a new state lockup angered people in a deep-red corner of rural America—and changed how some see incarceration.

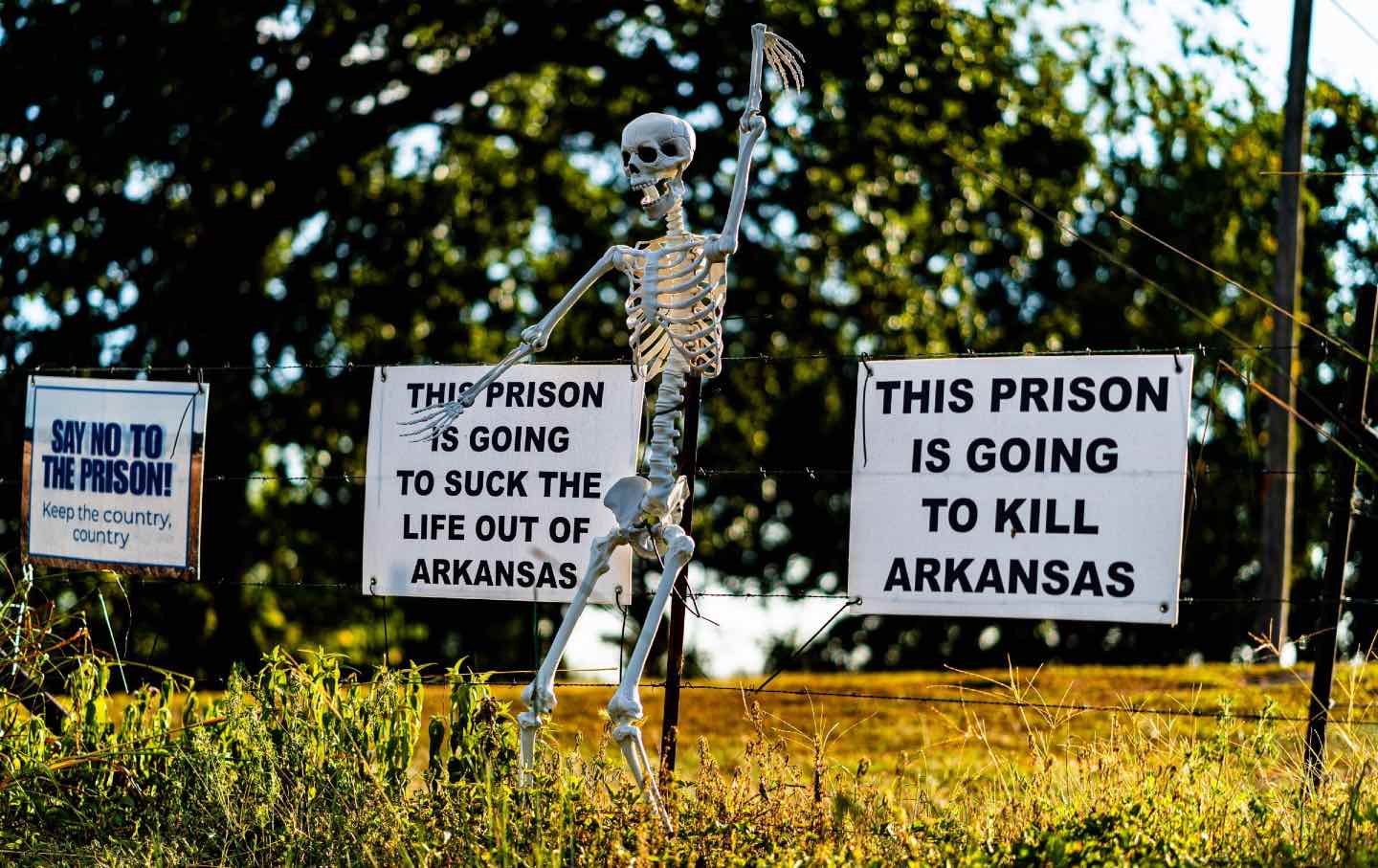

Protest signs have sprouted near the site of Arkansas’s next prison.

(Bill Gorman for Bolts)In 2001, Don and Bo Sosebee picked a spot for their house on a small hill overlooking a pasture where their horses and cattle roamed. They spent the next three years building a one-story cabin there. Don hauled in 6×12 logs from Mount Juliet, Tennessee, for the frame. He lined the interior walls with lumber from his old barn and nailed white pine across the ceiling. In the front of the house, he hoisted a metal roof atop columns of tree trunks to make a covered porch. It became the background for their friends’ family photos, and where Don hosted his daughter’s wedding.

A quintessential cowboy, even at 83, Don still puts on his uniform each day: a denim long sleeve Wrangler button-up shirt with dirt stains on the sleeves, jeans, boots, and a tan cowboy hat.

He tells stories in a slow and sure drawl. One he enjoys telling is how he ended up in Franklin County, Arkansas. As it goes, in 1918, his parents climbed into a covered wagon and rode north from West Texas to northwest Arkansas, after three years of drought made it impossible to run cattle. They settled one town over from where Don lives now. Growing up, his family had no electricity or running water, instead using kerosene lamps and suspending food into their well in buckets to keep cold.

Don’s father knew horses and passed along his knowledge to his son. Patience, Don learned, was the key to winning their respect. As a kid, he earned $10 a month breaking neighbors’ horses. He learned to make his own horseshoes, too—a necessity after the town blacksmith was shot dead by his mistress’ husband (another story he likes to tell). Don fell in love with ranching, and by age 20 he started buying land on nearby Mill Creek Mountain—locals describe it as more like a large hill—to ranch and train horses.

Since then, Don has acquired around 300 acres. He’s given some of it to his son, Cody Sosebee, a renowned rodeo clown, and his daughter, Shannon McChristian, who runs a daycare center 30 minutes away in the small city of Fort Smith. He’s filed plans to build a cemetery and intends to pass his land down to his great grandchildren.

Inside the cabin, Don and Bo cook breakfast on a wood stove. A pleasant smell lingers in the air for the rest of the day, like a sweatshirt airing out after a campfire. Rifles hang by the doorways, the walls are decorated with photos of the Sosebee children astride rodeo horses, and outside, a “pro-life, pro-God, pro-gun” yard sign is posted in front of the porch. The couple pride themselves on the self-sufficient life they’ve made on the mountain, which includes keeping cows for milk and beef, chickens for eggs, and a garden for vegetables.

Getting enough water is an ongoing chore. When they built their cabin, they figured they could get water from wells they dug around it for about $2,000 each, but only one produced enough water—and then it ran dry after the gas company drilled nearby. Now, every other day they drive a mile and a half down to the only other working well on their land to fill up barrels to haul back to their house.

On Sundays, they attend the Baptist Church, across the street from a small shed that contains the area’s fire department. Bo sings in the choir. Afterward, they head to Simple Simon’s Pizza, the only restaurant that’s open in the area on Sundays, to eat with their children, grandkids, and great grandkids. They know most everyone there and exchange warm hellos.

In truth, there are few strangers around Mill Creek Mountain. Hardly anyone locks their doors in the tight-knit community of mostly ranchers and farmers. Outsiders are fodder for gossip—the sight of an unfamiliar truck could spur a street-wide plenary about whom it might belong to.

So when news hit Facebook the day before Halloween last year that the governor, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, was planning to call into the local radio station, KDYN True Country, to make an announcement, speculation ran wild. The station usually ran bulletins about local events like fish fries or little league baseball signups, not appearances from the governor.

The next afternoon, Don and Bo turned on their radio and listened in disbelief as Sanders announced that the state had bought an 815-acre ranch next door to them and planned to build a 3,000-bed prison there. Sanders declared that the prison would be the “single largest economic investment in the history of Franklin County.”

It had been 30 years since Don had thought about prisons. He used to help with the prison rodeo in Oklahoma, and in the 1980s, he rounded up cattle and trained horses at Cummins Unit, a penal farm in Southeast Arkansas. He’d say he didn’t know enough about incarceration to offer an opinion about whether the state needed another prison (he trusted the governor on that), but he knew enough to know didn’t want to live next door to one.

Don and Bo, who share more than a mile of fence with the prison site, worried about what it might do to the life they’d built for themselves. The first change came shortly after Sanders’s announcement, when state workers put a lock on a gate Don used to let through cattle that had wandered off his property.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

The prison site, in the prairie below Mill Creek Mountain, was visible from Don and Bo’s land, just below the power lines that ran through both properties. Much of the land is untouched—save for a 2,800-square-foot cabin, horse barn, and rodeo arena—and some is only traversable on horseback. Around 30 homes neighbor the site, and more than 600 are within five miles.

Don and Bo, like more than 75 percent of Franklin County, had voted for Sanders, a Republican who became a national star in conservative politics after serving as White House press secretary during President Donald Trump’s first administration. Sanders was popular in the area, as was her father, Mike Huckabee, who as governor oversaw the last prison built in the state in 2004.

As Don found himself thinking and talking about prisons more than ever, he questioned his vote.

“I always thought, my whole life, I thought that’s the governor’s problem. Let them solve it,” Don told me in February as he sat inside his cabin eating lunch: hamburger pie made with fresh milk from their cows, and green beans, corn, and potatoes harvested from the garden. “I just voted farming…. that’s their department, let them run it. But they’re not running it. They’re not taking care of us.”

Situated in the rugged northwest corner of Arkansas, Franklin County, population 17,000, is a mix of mountainous terrain, rolling hills and sprawling farmland. The Ozark Mountains stretch across the northern edge of the county, ending in the Arkansas River Valley below—where the new prison would be located. The placid valley is mostly connected by craggy two-lane roads. The town closest to the new prison site, Charleston, has a population of just 2,600. It got its first traffic light about a decade ago.

The land around Mill Creek Mountain is good for ranching and hunting, but is also notoriously rocky. Thick slabs of sandstone sit below the surface, and in some places jut out of the ground. It could take half the day to drill through it with the best equipment.

Local opposition to the prison quickly grew forceful and widespread after the governor’s radio announcement. Farmers, teachers, and business owners of varying political persuasions were confused as to why state officials would pick the area for a new prison, questioning whether it was even feasible to build it there.

“We were just in shock,” Don’s daughter, McChristian, told me of her family and neighbors. “Because how do you live in the shadow of a mega prison?”

In a local Facebook group, those living in Mill Creek Mountain, Charleston, and the surrounding communities wrote posts contemplating the possibility that escapees would hide on their land. They worried that their kids wouldn’t be safe playing outside alone anymore. They thought of prison floodlights polluting their views of the stars at night. They considered their property values plummeting. Many residents had mineral rights, for which they received a small check each month. If the state used explosives to blow up the thick sandstone beneath the surface of the site, would the gas lines be compromised? What if the explosives disrupted the wells they depended on for water?

Then there were questions about how the state expected to find 800 people who wanted to work at the prison. Community members thought it would be impossible to hire everyone the facility needed locally, raising the possibility that more people would move to Franklin County. Even the local sheriff opposed the plan, worried the state prison system would poach away his deputies with higher pay.

Considering the challenges ahead, people in Franklin County also questioned how much the project would ultimately cost state taxpayers when it was all over. Sanders had estimated the prison would cost $470 million when she first proposed it in 2023, but looking at similar projects in other states, they suspected the bill would be much higher.

It was no secret that Sanders wanted a new state prison: She campaigned for governor in 2022 on putting more people behind bars in Arkansas, and soon after taking office she spearheaded the Protect Arkansas Act, sweeping legislation that created the need for more prison space by significantly limiting parole and bail. But where exactly that new prison might go had been a mystery until Sanders’s radio announcement.

People in Franklin County were also angry that they weren’t given a say, let alone even told the prison was going there until it was a done deal. While nearly one in five residents in Franklin County live at or below the poverty line, higher than the national rate, locals scoffed at Sanders’s promise that the prison would be an investment in them. Research on prisons in rural areas has shown that while they are often sold to rural residents as drivers of economic development, they largely fail to deliver on promises of prosperity even as they fundamentally alter the communities in which they’re built.

Within a week of Sanders’s announcement, locals organized a town hall meeting with state officials, lawmakers, and the governor’s staff inside the Charleston High School gymnasium. A host with KDYN moderated the evening, asking preapproved questions.

The two-hour meeting seemed to raise more questions than provide answers for nervous residents who packed the bleachers. Lawmakers representing the area said they’d only been notified about the project a few days prior to Sanders’s radio appearance, and that they staunchly opposed it. Asked why it had been kept secret, Joe Profiri, a former head of the Arkansas Division of Corrections (ADC) and now a senior Sanders adviser, told the crowd the state didn’t want to get into a bidding war that made building the prison more costly. “It was important for the taxpayers, with regards to ensuring that there wasn’t an escalation in the price,” he said to jeers emanating from the crowd.

Lindsay Wallace, the current ADC secretary, assured the audience that there was no downside when the state built a new prison in her family’s community in the early 2000s, when Sanders’s father was governor. “I don’t think there’s been any negative impact,” she said.

At the end of the tense evening, Don, who had been chosen by his neighbors to deliver closing remarks, strode to the podium on the gymnasium floor.

“I really think that the decision that’s made right now will cost our great grandchildren,” he said. “It will cost them for the rest of their lives before this thing is over.”

After the town hall, hundreds of community members got together to fight the prison. While the state had secured the land, the Sanders administration still needed to clear several hurdles to start construction, including getting lawmakers to approve funding for the project. Residents worked on mapping the homes around the site to show how many people the facility would impact. Others called and wrote e-mails to legislators in Little Rock, urging them to vote against bankrolling the prison.

As part of their work, they used state public records laws to obtain hundreds of pages of records, including contracts and agency e-mails from half a dozen state staffers, documenting how state officials had decided to build the prison in Franklin County.

The records, which organizers shared with me, only further fueled their anger at the project, showing that state officials tried to keep it hidden from residents and local lawmakers while also glossing over basic questions about the viability of the site. In one e-mail, a state employee compared Franklin Countians to a “white trash redneck conservative” character in a South Park episode. After locals publicized the insult, the employee apologized and was removed from work on the project.

The records also showed that two counties in southwestern Arkansas had lobbied state officials for a new prison after ADC started looking for land soon after Sanders took office. But the agency was already eyeing land around Franklin County as early as February 2023, when ADC secretary Lindsay Wallace flagged property near Fort Smith. That summer, an architecture firm estimated that it would cost $1.2 billion for the state to build a prison.

The state was initially looking for at least 250 acres with enough of a nearby population to staff the prison, and with some preexisting infrastructure like water and electricity. The property also needed to be close to emergency services and hospitals. Officials considered the location the most important factor, saying it had to be at least 60 miles away from other ADC facilities. In November 2023, Profiri, then still head of the prison system, also told lawmakers during a hearing that “the community has to embrace the fact that a prison would go into their community or near their community.”

Then, early last July, Shelby Johnson, a director of the Arkansas’s Office of Geographic Information Systems, an agency responsible for cataloguing the state’s land, saw a listing, titled “Franklin County Cattle Farm,” on the rural real estate website Habitat Land Company, and sent it to his colleagues. He warned that the property had its shortcomings, writing, “Workforce numbers are not great, and accessibility is not great.”

Nevertheless, Johnson’s team moved quickly on a contract to purchase the ranch for $2.95 million, or $36,000 above asking price, at the end of July 2024. Johnson seemed eager to keep the deal secret.

“Do we have a code word [aka – Operation Star Dust]…for this project?” he asked in an e-mail.

As the state worked to finalize the land purchase, staff continued to actively hide their plans. When a staffer with the Arkansas Development Finance Authority, the agency that was to buy the land and then lease it to the corrections department, wrote an e-mail asking to put the prison project on the agency’s August 2024 meeting agenda, the agency’s chief legal counsel wrote back denying that it was for a prison. “Its not for a prison tho [sic]. It’s a land purchase in Franklin County and we are purchasing it to pursue our own corporate purposes,” he responded.

Two-and-a-half months after the state entered into a contract to buy the Franklin County ranch, state staff asked the Arkansas Legislative Council, a group of state senators and representatives who review contracts between legislative sessions, to approve a $16.5 million contract with California-based Vanir Construction Management to oversee the project. When the council deliberated the contract at a hearing, Representative Joy Springer questioned Anne Laidlaw, director of building authority for the Arkansas Department of Shared Administrative Services, an agency that was in charge of finding land for the prison, where the state planned to build the facility.

“We have not selected a site yet, so we’re still working on that,” Laidlaw told lawmakers.

When Springer pushed for more information on where in the state the prison would be located, Laidlaw replied with a smile, “We’ve looked at sites all over the state.”

Two weeks after that hearing, Sanders announced her plans to build in Franklin County.

Sanders’s team also kept details of the project from the state’s Board of Corrections, which is in charge of managing ADC’s finances but only found out about the land purchase just prior to the governor’s announcement. About a week after Sanders revealed the site, Johnson, the director of the state’s land agency, provided a two-page “Site Summary” to board members outlining for the first time how the state selected the ranch. He wrote that his team had started with 25,000 potential sites that met the criteria, then narrowed it to 6,000. They ultimately visited 14. He wrote that soil and excavation experts had done an informal consultation in Franklin County that didn’t raise any issues, but said they might need to bring in water from nearby towns. His prior concerns about workforce numbers and accessibility seemed to be alleviated; Johnson concluded that the site “meets the search criteria.”

I sent detailed questions about the project to Sanders’s office, and the Department of Transformation and Shared Services, the agency where Johnson and Laidlaw work. Neither office responded.

Astounded by the lack of preparation that went into the deal, locals posted screen grabs of damning documents on Facebook, asking their neighbors to share, and attached them to e-mails to state officials and the media showing what they had found.

I visited Franklin County in February while the legislature was in session and lawmakers had yet to vote on funding for the prison. After lunch at a barbecue joint where Don’s picture hung above the cash register—a tribute to his speech at the town hall, the owner told me—his daughter, McChristian, drove me to the prison site. A weathered wooden arch flanked by piles of sandstone slabs marked the entrance. Signs warning “NO TRESPASSING VIOLATORS WILL BE PROSECUTED” stood in the ground along the property line.

Neighbors had posted their own signs across the street, with sayings like “MAKE AR GREAT AGAIN IMPEACH SANDERS” and “BLINDSIDED WITHOUT A SAY!” Someone had placed prop skeletons wearing striped prison uniforms along the fence.

McChristian carried a binder filled with public records, talking points, and other notes she’d gathered on the prison. An image of her father riding a horse into the sunset, emblazoned with the text: “My why… #MOVETHEPRISON” was taped to the front cover.

Since making the binder, she had a new goal: stopping the prison altogether. People outside of Franklin County derisively labeled her and others’ opposition to the prison as NIMBYism (“Not In My Back Yard”) and said they deserved the lockup because they had voted for Sanders. McChristian says she’s grappled with the criticism, admitting she’d been “naïve” about incarceration in the state.

“As I’ve come to know more and more, I’ve just been horrified about our entire prison system,” she told me. She talked about wanting state officials to tackle root causes of crime, like poverty and poor education, and prioritize programs to keep people out of prison after release.

“My NIMBY stance was for my family property in the beginning. Now it’s for my whole state,” she told me. “I say no, we don’t want a prison. We don’t want this mega prison in this state. We don’t need this mega prison in this state.”

Arkansas’s new prison adds to a wave of expensive mega prisons now being built across the nation. In Alabama, Governor Kay Ivey spearheaded the construction of a 4,000-bed prison that will be “larger than a lot of county seats” in the state, according to one lawmaker. The cost of the prison, which will be named after Ivey, was initially estimated at $623 million, but increased to more than $1 billion due to rising construction costs.

In 2023, Indiana broke ground on a $1.2 billion, 4,200-bed prison that is set to be the most costly project in state history. Utah, which in 2017 broke ground on the 1.3 million-square-foot prison that was expected to cost $650 million, ultimately spent more than $1 billion before its completion in 2022, as officials blamed higher construction costs and Trump’s tariffs on China during his first term.

The new mega-prison projects are an echo of the prison-building boom in rural areas during the 1980s and ’90s, following the tough-on-crime policies of the era. The land was particularly attractive to government officials looking to build new prisons: It was cheaper, larger, and they had an easier time selling the facilities to rural residents than to wealthy urbanites, who ferociously campaigned against facilities in their communities.

During her campaign for governor, Sanders blamed violent crime in Arkansas, which far exceeds the national average, on “the dangerous ‘defund the police’ rhetoric and anti-law enforcement policies of the radical left,” and also a lackadaisical parole board that she accused of releasing too many dangerous people—even as the state maintains one of the highest incarceration rates in the country, behind only Louisiana and Mississippi.

In Franklin County, some residents who voted for Sanders started to regret their support after the prison was announced. Ronni Young, a Charleston resident who grew up on her family’s dairy farm a mile and a half from the prison site, said her family voted for Sanders in the last election but now promises to campaign against her next cycle. Young’s parents, David and Jeanne Tate, still live on the 350-acre property, which is divided between a home surrounded by sprawling pasture with their dairy operation, and the prairie, where they farm hay. Young’s parents plan on being buried at the “Tate Cemetery” down the road, where her grandparents and great-grandparents lie.

When I visited her family’s farm, Young prickled at how officials had handled the project. “They thought we were just white trash rednecks and that we would just roll over and take it and not say anything,” she told me.

David recounted memories of waking the kids up early to milk the cows and watching the sunset over Tater Hill, a dirt mound the local army base previously used for artillery practice. He shared many of the same concerns of the more than a dozen people I spoke with during my trip—water, high taxpayer costs, and government mismanagement were chief among them. “You know, it’s not the most glamorous place in the world, but it is to me,” he said.

Jeanne walks a three-mile loop around the family’s property every day, and told me she’s nervous she’ll run into prisoners tasked with picking up trash on the side of the road; “I don’t need no prisoner walking with me to pick up trash, okay?”

The family, whose approval of Sanders’s father largely motivated them to support her in 2022, told me they disagreed with the governor’s plans to lock more people up.

Sanders’s Protect Arkansas Act, which she signed into law in 2023, abolished parole for people convicted of a long list of crimes, ranging from the most serious offenses like child sex abuse and first-degree murder to much less serious crimes, such as fleeing or having a gun while engaging in a Class B felony—a category that encompasses many drug crimes. Under another provision, prisoners convicted of a long list of crimes, such as performing an abortion in violation of the state’s ban, arming rioters, or trafficking controlled substances, aren’t eligible for parole until they serve at least 85 percent of their sentence. The bill also made it more difficult for people in jail pretrial to get out on bail.

Experts say that the legislation, which saw overwhelming support from Republicans and passed on a nearly party-line vote, will make it even harder for people to get out of the state’s already overcrowded and understaffed prisons. In 2023, staffing shortages were so bad that the chairman of the Board of Corrections requested that Sanders call in the National Guard.

The crisis has been compounded by probation and parole systems that routinely cycle people back into prison. Nearly three-quarters of people admitted to Arkansas prisons over the past decade were on probation or parole, according to a report by a task force created by the Protect Arkansas Act to investigate high recidivism rates.

Arkansas’s parole system has the worst track record in the country: In 2023, the most recent year with available national data, more people on parole were sent back to prison in Arkansas than in California and Texas, which are at least 10 times more populated.

Olivia Fritz, a legal fellow at the MacArthur Justice Center’s National Parole Transformation Project, which is investigating Arkansas’s parole system, says she and her team found that prisoners often had their parole revoked for reasons such as forgetting to check in with their parole officer or failing to pay a $35 monthly supervision fee. At revocation hearings, prisoners were also regularly denied certain rights they were supposed to be afforded, such as access to lawyers or the opportunity to present evidence in their favor. The majority of people waived their right to a hearing altogether on the advice of their parole officers, according to data on parole revocations that Fritz obtained from a public records request.

“Those due-process protections aren’t being implemented,” Fritz told me.

Ed Powers, chair of the Department of Sociology, Criminology, and Anthropology at University of Central Arkansas, is optimistic about a provision in the Protect Arkansas Act aimed at improving programming to reduce recidivism. But he says that issues the state has long struggled with—like poverty, addiction, and racial segregation—won’t be fixed by a new prison. “I do think that people ought to consider how much of their tax money is being spent on a system like this, especially if there’s not a lot of evidence that the system is really working,” he said. “I think that if this particular trend continues, that we’re going to be looking at more overcrowding in just a few years, even if we build a 3,000-bed facility.”

Kaleem Nazeem, an organizer with the prisoner advocacy organization Decarcerate Arkansas, was incarcerated at Cummins Unit, the prison where Don trained horses in the 1980s, from age 17 until he was released in 2018, when he was 45 years old, after the US Supreme Court ruled that automatic sentences of life without parole for juveniles are unconstitutional.

“We can’t build our way out of the problems that we’re seeing,” Nazeem told me. “If we educate individuals while we have them incarcerated, instead of building prisons, we can start closing prisons.”

Halfway across the country, in another Franklin County nearly 1,200 miles northeast of Arkansas, prisons have become the lifeblood of the community.

Prisoners make up about one-fifth of the population in Malone, the seat of Franklin County in Upstate New York. Three prisons sit within a five-minute drive from the main street in town, two of them along the same road—the medium security Franklin Correctional Facility, and Upstate supermax. The third, the medium-security Bare Hill Correctional facility, is nearby, just past a farmstead and a half dozen single-wide trailers.

Jack Norton, an assistant professor of criminal justice at Governors State University in Illinois, grew up in nearby Washington County. Along with Franklin County, it’s a part of a region of northern New York nicknamed “Little Siberia,” known for the mountainous terrain of the Adirondacks and, during Norton’s childhood, the rapid construction of new prisons. The state built 11 new correctional facilities in the area between 1982 and 1999, in the wake of the 1971 Attica uprisings and the War on Drugs. Locals welcomed and even requested many of them.

Norton has closely studied prison expansion in the region, exploring how the area became so deeply entrenched in the business of incarceration, and is now at work on a book on the topic. As part of his research, he interviewed business owners who had asked for the prisons in Malone. Their motivation, he says, was self-preservation, as business leaders saw the prisons as the solution to stop people from moving out of town following the recent closure of mills and iron mines.

This expansion ended up providing hundreds of jobs, and turned Malone into a prison town. And once that became its identity, it also seemed to shut the door on Malone’s ever developing into anything else, Norton told me. “You know, it’s like the kids are leaving the town. We need to do something to keep people here, or we’re gonna become a ghost town. That’s what they did, is they transformed the town.”

When I visited Malone in August, barbed-wire coils outside the prisons glistened against bushy pines and green corn stalks that rose from the fields surrounding them. Shadows of guards manning the watchtowers were visible from the parking lots, a reminder of the 2,200 men imprisoned there. On average, people incarcerated inside are more than 230 miles from home; more than a third are from New York City. Visiting from the city entails driving more than six hours each way or taking nearly 10-hour bus trips.

“If it wasn’t for these correctional facilities, this place would be really depressed,” Franklin County sheriff Jay Cook, a Republican, told me when we met in his office across the street from Franklin Correctional. Cook grew up on his family’s farm in the small village of Burke, where there were seven farms on his road alone. But when Franklin Correctional opened in 1986, Cook says his brother and many of his friends left their farms to work at the prison. “They were the best-paying jobs around at the time,” he told me. Cook went into the military and without anyone to pass it down to, his father sold the farm.

These days, small-scale farms have become increasingly rare as they’ve mostly been overtaken by large industrial operations with thousands of cows. Some are members of Agri-Mark, a dairy cooperative with $1 billion in revenue that makes products for Cabot Creamery.

The sheriff told me that the only good jobs left are either in government, law enforcement, education, or corrections. The county has a low unemployment rate that hovers around 3 or 4 percent but still struggles with drugs. And despite its small size, Franklin County ranks 21 in highest incarceration rate per capita of the state’s 62 counties, the think tank Prison Policy Initiative found. The poverty rate is around 16 percent, compared to the national poverty rate of 11.1 percent. Nearly half of residents don’t go to college.

Cook waved off questions about whether these issues were a consequence of the prisons, assuring me that they’ve been good for the area. “It helps the economy. You know, they purchase UTVs, ATVs, snowmobiles,” the sheriff said of people who work at the prisons. “If it wasn’t for these facilities, that business would be probably down the tank.”

Down the road, Monica Beebe and her son, Christopher, were outside painting their restaurant, The Pines. A yard sign printed with “We Stand with Corrections,” a remnant of the guard strikes earlier this year, was affixed at the entrance. The place had operated as a bar since 1988 until the Beebes bought it in 2018 and turned it into a restaurant serving dishes like Adirondack poutine, flatbreads, burgers, and pasta. Corrections officers are among their regulars.

Monica, who described herself as liberal, says she was working at a grocery store when the state opened Franklin Correctional, and half of the staff quit to work at the prisons. She says her husband, two sons, son-in-law, and daughter-in-law are all employed by the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision. She told me that many people would probably pack up and move if the prisons left. “I told my daughter, who’s a teacher, I said, you know, if the prisons ever go out, it’s going to be on you and Christopher, because you’re the only two people in the family that don’t work for corrections.”

In the village’s business district, which in the spring was awarded $10 million from the state for revitalization, the sidewalks were empty. At least a dozen storefronts sat vacant, with signs advertising businesses that once operated inside still painted on the glass windows. A stately Victorian building on the corner that was once home to the Flanagan Hotel was patched up with plywood boards, and glass was punched out of its windows; the town police now post warnings about trespassing inside the hotel, where Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell once stayed, saying one misstep on the old decaying floor could be deadly.

Whatever activity was left in town seems to have moved a few blocks to the west, where chain fast-food restaurants lined the street and cars filled the Red Roof Inn and Walmart parking lots—which opened in 1994 and 2006, respectively, coinciding with the opening of prisons.

On the way back to my hotel, I stopped in Dannemora, the prison town at the center of the 2015 manhunt for two prisoners who escaped the largest maximum-security prison in the state, Clinton Correctional Facility, with the aid of their shop supervisor. The supervisor, Joyce Mitchell, lived around Malone and worked at the Tru-Stitch shoe factory in Franklin County until it shut down in the early 2000s; her trysts with the two prisoners was portrayed in the Ben Stiller–directed Showtime drama, Escape at Dannemora.

The prison remains the centerpiece of this town of 2,800 in more ways than one. More than a third of its residents are incarcerated. Beige, 30-foot concrete walls run along the rectangular block that houses the prison, abutting a main street with a pizza place, liquor store, and grocery store containing a pharmacy and Dunkin’ Donuts. A clerk inside the store who rang me up told me the imposing presence of the prison was “nothing out of the ordinary,” explaining that many generations of her family worked there.

New York’s Franklin County looked like a version of the future that residents feared in Franklin County, Arkansas. Prisons had overtaken the industries that had once defined life there, undeniably changing the area. Even if residents seemed content with the arrangement, it had been sold as their only option for keeping food on the table.

Judah Schept, a professor of justice at Eastern Kentucky University who studies the history and political economy of the carceral state, told me that government officials have often targeted struggling towns suffering the effects of deindustrialization, promising that prisons would bring economic prosperity. In Eastern Kentucky, where Schept conducted his research, the federal government built three prisons in the 1990s and 2000s. At the time, the coal economy was declining and unemployment was high, and the prisons were enticing for residents looking for a way out.

Schept says that locals bought into the guarantee of a booming prison economy so heavily that they applied for federal grants to improve their infrastructure and changed the school curriculum to prepare children for jobs at the prison. But prosperity never materialized; the three counties where the prisons were built remain among the poorest in the poorest congressional districts in the nation.

“Prisons are proposed as a kind of all-purpose solution, even though they kind of rarely deliver on promises of economic development, or at least the delivery of economic development is really uneven,” Schept told me. “Generally speaking, the worse a community is economically, the less of a positive impact a prison will have.”

Rural prisons have been the subject of intense research, with those studying them largely concluding that they don’t drive economic growth.

In 2010, a team of researchers from Washington State University found that counties where a large proportion of residents didn’t go to college were the least likely to benefit from prisons, even as leadership in those counties were also more likely to seek out prisons as a solution to their economic problems. “Prisons are doing more harm than good among vulnerable counties,” the team concluded.

As for the jobs, many of them end up going to people living outside of the counties housing the new prisons. Less than 40 percent of jobs in California’s rural prison towns were filled by current residents, according to Ruth Wilson Gilmore, a prison scholar and author of the book, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California.

Prison building can put more strain on existing small businesses, since a proliferation of chain stores often follows and causes local businesses to go under. In Tehachapi, California, for example, 741 local businesses closed during the 1990s as chain stores took over in the wake of two new state prisons, the rural prison researcher and filmmaker Tracy Huling wrote in her 2002 article, Building a Prison Economy in Rural America.

The construction of prisons in rural areas inevitably creates a relationship in which residents ultimately become engulfed by incarceration.

“You know, you pop a city, a city down in the middle of a rural countryside and over time…you tend to have a company town effect, where these communities become very dependent on the prison and the state for lots of things,” Huling told me in a telephone call. “The self identity of a place changes.”

Corrections officers have a higher rate of divorce and substance use. One study found that 34 percent of officers suffered from post traumatic stress disorder, compared to 14 percent of military veterans and 7 percent of the population.

“The people who go home at night, they bring that stress and tension outside into their families and neighbors and friends and communities,” Huling said. “The prison almost begins to imprison the community in a way, or create a very similar kind of atmosphere.”

Adam and Taylor Watson moved from Texas to a farm just outside Charleston, Arkansas, more than two years ago, in part because they were tired of living near a state prison outside of Houston. They felt like they couldn’t escape it, frequently running into prison staff at the store, restaurants, and bars.

Adam, who makes high-purity gas for cannabis companies to extract THC for hash oil, says the difference in state drug laws also helped inspire the couple’s move to Arkansas. When I visited their 50-acre farm, a 20-minute drive from the prison site, Taylor was making waffles with eggs she’d harvested from her chickens that morning.

Much more politically left-leaning than their new neighbors, Adam and Taylor say they were against prisons even before Sanders announced the prison project near their new home last year. The couple has since emerged as leaders in the local fight against the facility, drawing on Adam’s experience as a paralegal and Taylor’s background in fundraising to create Gravel and Grit, an organization of locals opposing the new prison. Adam has spearheaded trips to Little Rock to speak with lawmakers, as well as filed dozens of public records requests that have helped inform the community’s understanding of the project. He told me he spends 40 hours a week doing work to stop the prison. Taylor has put together a chili cookoff and spring dance to raise money for their campaign.

The Watsons’ efforts have landed them in an unlikely alliance with much more conservative neighbors who previously supported Sanders and hadn’t before questioned her push for more incarceration in the state.

Based on his experience in Texas, Adam fears that the Franklin County prison will, as he puts it, “cannibalize the area around it.”

“All of a sudden, you know, the majority of the population is either working there or working in an industry that supports it,” he says. “And you have a town that won’t criticize it because they’re beholden to it.”

Taylor doesn’t flinch when I ask her why she opposes the project.

“I don’t want to raise my son in a prison town. I mean, that’s the quickest answer, right?”

On the Sunday of my visit in February, nearly two dozen Franklin County residents gathered at an event space in Charleston to listen to State Senator Bryan King, a chicken farmer who represents parts of the county. King, who wore a checkered shirt, cowboy boots, and a baseball cap, told residents that lawmakers in Little Rock were struggling to deal with the “three-headed monster” of high crime, high incarceration rate, and severe prison overcrowding. But he told them the governor’s solution would be a fiscal calamity for the state.

“There is no way the state’s going to afford what we’re fixing to go down,” he told residents. “Look at Alabama, look at Utah. These prisons, these mega prisons, are mega financial disasters.”

The senator, a Republican who had voted for Sander’s Protect Arkansas Act and has previously proposed legislation to put more people in prison, told residents he’d devised a plan to stop the prison via legislation to instead spend $400 million expanding partnerships with county jails to house prisoners, which he wanted to finance with state revenue from casinos and medical marijuana. (To help ease overcrowding, the state already pays county lockups around $30 million per year to house prisoners).

One woman attending the meeting suggested that King and other lawmakers look into funding more programs to prevent incarceration in the first place. “Instead of people being like, ‘Well, I don’t know how to do anything except sell drugs,’ boom, we’ll teach you how to be a diesel mechanic,” the woman said. “Boom: We’ll teach you how to do brick work, carpentry, all these things. We need people that will work.”

King considered her suggestion. “We know what is not working now, and you know, at some point in time, you got to try something different,” he responded. “But right now, you know, it is about being against the government and the governor right now.”

Soon after the community’s meeting with King, other lawmakers began to join the local opposition: In late February, the state legislature’s joint budget committee voted against awarding the state $330 million dollars for the facility after state officials couldn’t answer questions about the overall cost of the project and size of the facility.

“We need to know right now, today, as soon as possible, what is the estimate? When is your completion date?” King said during the hearing. “This is nothing I wouldn’t do in regular business.”

Days later, Vanir, the project manager, clarified in a letter that the prison would cost at least $825 million, nearly double the $470 million that Sanders estimated in 2023. In response, lawmakers introduced a bill to allocate $750 million with the possibility of amending the amount up to $1 billion.

Sanders launched a public information campaign to pressure lawmakers to pass the funding bill, posting a video of sheriffs supporting it; notably, Crocker, the Franklin County sheriff, was not involved. The bill ultimately died in the state Senate after five failed votes over the course of the first week of April.

The lack of support in Little Rock has not deterred Sanders, who still plans to build the prison in Franklin County. The state has $75 million previously allocated through former Governor Asa Hutchinson to use on preconstruction costs. In June, the Board of Corrections authorized spending $50,000 more to drill two wells to try and find water.

“I don’t have a lot of words for how stupid it is,” Adam from Gravel and Grit told me in an April phone call. “You might as well just pile up $75 million and light it on fire.”

In late June, the engineering firm on the project, McClelland Consulting Engineers, issued a preliminary report on the site detailing several problems that would have to be mitigated to proceed with the project, and incur additional costs. Many mirrored concerns that locals had flagged when they learned of the project last year. The engineers said that the land must be stripped at least a foot deep to proceed with construction and recommended an independent archaeological survey. They also pointed to endangered species of bats that live on the site.

Unsurprising to locals, the firm also noted potential issues with water, as there’s no aquifer on the site to supply large amounts of groundwater; all of the homes in the surrounding area rely on wells.

If there isn’t enough well water, the state has said it could pipe in water from either Fort Smith or the nearby town of Ozark. But leadership of both places have said that their infrastructure is already stretched and isn’t equipped to supply a 3,000-bed prison. In Fort Smith, engineers found in June that it would take between three and six years to make upgrades to the city’s water system so that it could produce enough for the facility.

Jack Wells, system manager for RiverSouth Rural Water District, a water company that supplies residents of Franklin County and surrounding counties, told me that the prison project “has been a burr under the saddle.” One of his company’s water lines runs in front of the property, though Wells said it doesn’t have enough capacity to supply the prison. State officials listed him as a “key contact” in the site assessment they released shortly after they bought the land, but he says he hasn’t heard from them.

“That tells me that they’re either got a lot of money to throw at or they don’t know what they’re doing,” Wells said.

The Arkansas Valley Electrical Cooperative Corporation, or AVECC, the company that would be in charge of supplying electrical power to the site, was also listed as a key contact for the project, yet still hasn’t been contacted by the state. Brandon Fisher, the company’s technology and communications manager, told me in an e-mail that AVECC only learned of the prison when Sanders announced it to the public. He wrote that the company has attempted to make contact with officials in order to evaluate the site, but as of late July “we have had no formal communication with the state regarding the construction of the prison facility.”

As the project slows, more people have joined the fight to oppose the prison. Members of the Chickamauga Nation, a Native American group with historical ties to Arkansas, say that they worked with an archaeologist who found that the land may contain burial sites and would have been sacred ground that must be preserved. Under the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, human remains and sacred objects are protected. Arkansas law also protects Native American remains, but Sanders has dismissed the Chickamauga’s concerns.

Sanders could still ask for the funding this year if she calls a special session. Otherwise, officials would have to wait until spring 2026, during the legislative fiscal session.

Rand Champion, chief of communications for ADC, told me in an e-mail that the project “is currently on hold as legislators review documents and information.” Champion said officials are still waiting on the state’s legislative council to approve funding for a $57 million contract with an architecture and engineering firm; the soonest the council could consider that contract would be its meeting scheduled for the end of September.

Local opponents of the prison continue to press their case before state lawmakers. This week, Adam testified at a joint legislative committee to present a formal complaint local citizens filed this summer alleging “acts of impropriety and malfeasance surrounding the proposed prison in Franklin County.” Their complaint also asks for a full investigation into the “highly secretive project.”

Johnson and Laidlaw, the state staffers who helmed the search for a site, testified during the contentious four-hour hearing, as did two members of the Board of Corrections. Profiri, the Sanders’s adviser involved with the project, had been called to testify before the committee but didn’t show. (One lawmaker called his absence a “slap in the face.”)

Johnson told lawmakers he was still convinced that the Franklin County ranch was still the state’s best option. Laidlaw testified that other sites the state considered weren’t viable or fell through during negotiations with sellers.

Still, when pushed by lawmakers, none of the state witnesses could say how much even just the search for water around the site might end up costing.

Visibly bothered, Representative Jim Wooten, a Republican, fumed, “I am for a prison.… But the location that we picked is the wrong one.”

Benny Magness, who chairs the Board of Corrections, estimated during the hearing that the state had spent less than $5 million on the project so far. Another board member, Lee Watson, said towards the end of the hearing that the state needs to figure out how to add prison beds “the fastest,” with the Protect Arkansas Act going into effect. “Growth is fairly predictable now, and it will be for the next four or five years, but it’s expected that that’s when the Protect Arkansas Act is going to start having a greater impact on our prison population, and we need to get ready for that.”

The hearing closed without lawmakers taking any action on the complaint by Franklin County residents.

As the project still looms over the area, Jason Kilbreath, a real estate agent with Keller Williams who does business in Franklin County, told me that prospective buyers—usually farmers or hunters—are avoiding anything near the site. “What I’m seeing is more hesitancy to buy in that area because of the potential prison that’s coming,” he said. “There’s just a lot of uncertainty and unknowns about the situation.”

In the meantime, the prison has pushed more residents of Franklin County into politics. Some are thinking about running for office. Others are reconsidering their years of voting straight Republican.

In late August, I spoke with Don Sosebee over the phone. A few days before, the Arkansas Department of Agriculture released the results of the two test wells it had drilled in the area, which barely yielded enough water for a house—far less than what would be needed for the prison.

Don worried that the state would continue to drill wells to pull water from the creek that flows through both properties and run it dry. “It’s a real concern,” he said. “It’s whether you can live here or whether you can’t, is what it amounts to.”

He told me the state had yet to approach him.

At the end of our call, Don gave the phone to his grandson, Jonathan Tedford. Tedford lives with his family across the way, and his land also borders the prison site. He said local critics of the project felt vindicated by the state’s failure to find water. “They looked at us and thought we were just a bunch of hillbillies,” he said, “and they are starting to find out that we were right.”

As an equipment operator in the oilfields, Tedford told me that he’d spent a lot of time around prison towns and wouldn’t have wanted to raise his family in any of them. He said he wouldn’t blame his children and grandchildren if they eventually wanted to move away because they didn’t want to live near a prison.

“That’s the kind of thoughts that eat me alive,” Tedford said, “knowing that a man took his entire life to put something together, to leave an inheritance to his family and that can be taken away just because the government decided they want to build a prison somewhere.”

Sustain independent journalism that will not back down!

Donald Trump wants us to accept the current state of affairs without making a scene. He wants us to believe that if we resist, he will harass us, sue us, and cut funding for those we care about; he may sic ICE, the FBI, or the National Guard on us.

We’re sorry to disappoint, but the fact is this: The Nation won’t back down to an authoritarian regime. Not now, not ever.

Day after day, week after week, we will continue to publish truly independent journalism that exposes the Trump administration for what it is and develops ways to gum up its machinery of repression.

We do this through exceptional coverage of war and peace, the labor movement, the climate emergency, reproductive justice, AI, corruption, crypto, and much more.

Our award-winning writers, including Elie Mystal, Mohammed Mhawish, Chris Lehmann, Joan Walsh, John Nichols, Jeet Heer, Kate Wagner, Kaveh Akbar, John Ganz, Zephyr Teachout, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Kali Holloway, Gregg Gonsalves, Amy Littlefield, Michael T. Klare, and Dave Zirin, instigate ideas and fuel progressive movements across the country.

With no corporate interests or billionaire owners behind us, we need your help to fund this journalism. The most powerful way you can contribute is with a recurring donation that lets us know you’re behind us for the long fight ahead.

We need to add 100 new sustaining donors to The Nation this September. If you step up with a monthly contribution of $10 or more, you’ll receive a one-of-a-kind Nation pin to recognize your invaluable support for the free press.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and Publisher, The Nation

Lauren Gill

Lauren Gill is a staff writer at Bolts. She previously worked as a reporter for The Appeal, Newsweek, and the Brooklyn Paper. Her reporting on the criminal legal system has also appeared in ProPublica, Rolling Stone, The Intercept, Slate, The Nation, and The Marshall Project, among others.