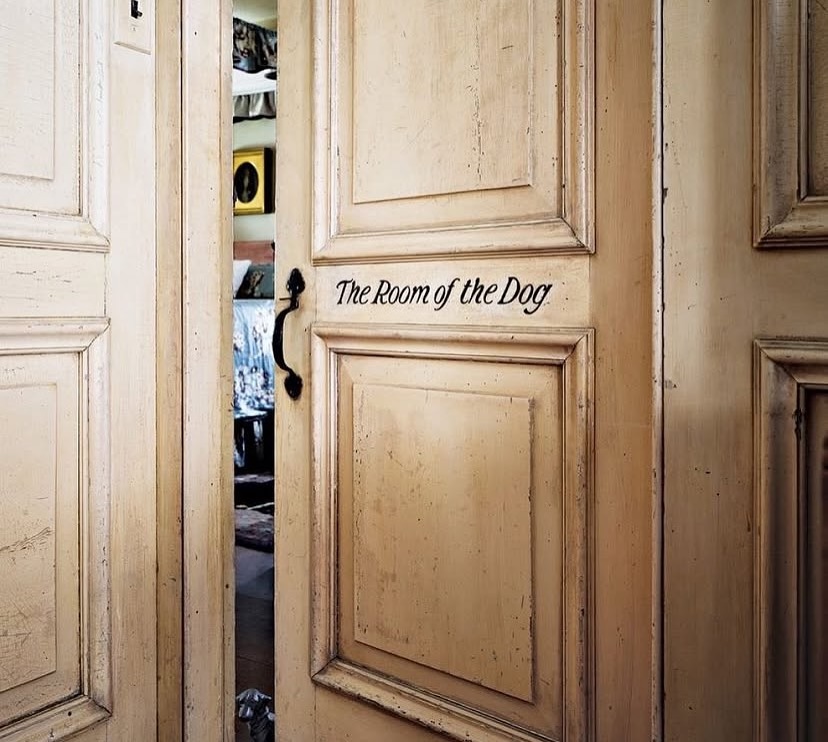

1. Who is the countess living in the Port of Missing Men?

On the edge of Scallop Pond in Southampton, an 85-year-old noble holds court in a hunting lodge dating to the Jazz Age that she is determined to protect. Photographs by Thomas Loof.

An article from New York magazine, found here.

2. Just some Teapot Ghost Dolls

By artist Pantovola.

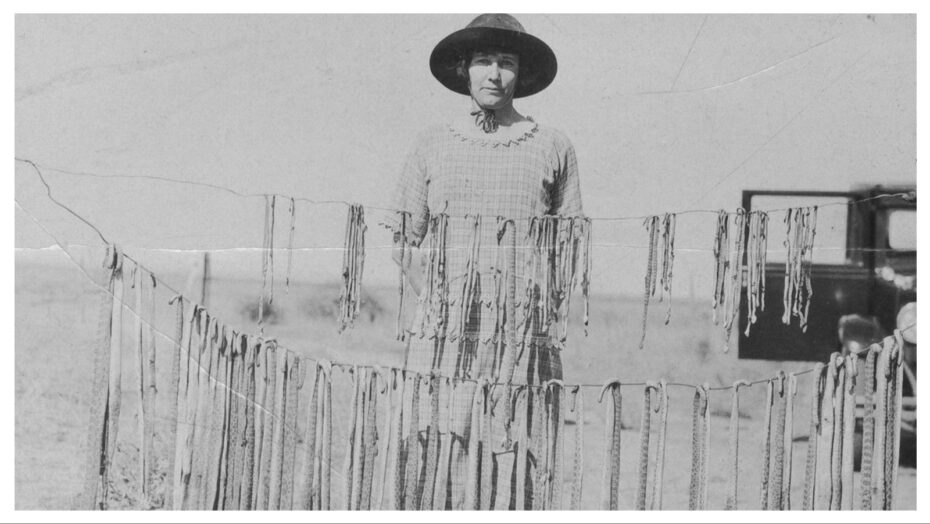

3. Rattlesnake Kate, a woman who famously and singlehandedly slaughtered 140 rattle snakes

One of the more interesting Wikipedia pages out there: in the 1920s, Katherine McHale Slaughterback (her real name) slaughtered 140 migrating rattle snakes when she found herself and her son surrounded while on horseback. Afterwards, she made herself a dress, shoes and a belt from the snakeskins (pictured above).

Read the full article found on Wikipedia.

4. A mother’s letter to her son-in-law, written 1,800 years ago

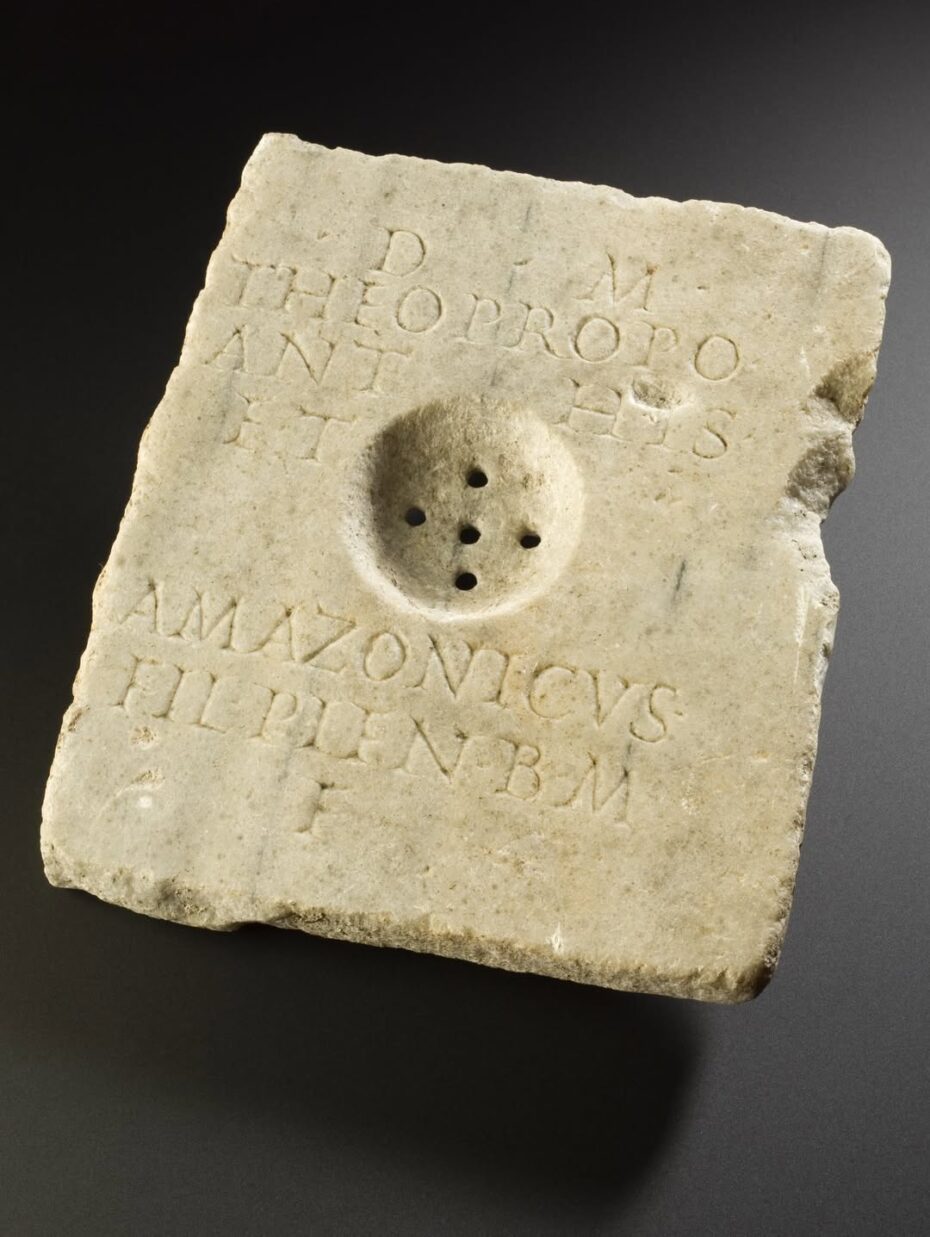

5. Roman Grave Marker for Pouring Libations (wine, milk, honey, water or oil) into the grave

Beginning with the words “To the Spirits of the Dead”, this sepulchral slab was dedicated to a man, Theopropus, by his parents. The slab would have lain on top on a grave and underneath its stone cover were holes so that wine, milk, honey, water or oil – known as libations – can be poured into the grave. Libations were offered to the ghosts of the dead to feed them in the afterlife. Another theory is that the offerings were to prevent the dead haunting the living. The slab was originally part of the Gorga collection owned by Evangelista Gennaro Gorga (1865-1957), a famous Italian opera tenor. The Gorga collection of mostly Roman instruments, votive offerings and pharmacy ware was bought in two parts by Henry Wellcome in 1924 and 1936.

More found on the Collection of the Science Museum, London.

6. A Brief History of Headstone Photo Ceramics

In 1854 two French photographers, Bulot and Cattin, patented a process to adhere a photographic image to porcelain or enamel by firing it in a kiln. The original ceramic pictures were done in black and white and then mounted on gravestones. The process caught on throughout Eastern and Southern Europe, and Latin America.

For the first time, ceramic pictures made it easy and affordable for the graves of the working class to be personalized with a likeness of the deceased. Before this only the wealthy had sculptures, busts, and carvings done in their likenesses on their tombs.

In 1893, the J.A. Dedouch Company began in Oak Park, Illinois. They quickly became one of the most popular companies that manufactured ceramic tombstone pictures.

By the turn of the century this type of personalization was becoming very popular and available around the world. The 1929 Montgomery Wards & Company Monuments catalog sold ceramic pictures for gravestones and described them as eternal portraits that “endow the resting place of the dead with a living personality.” Priced from $6.50 to $13.50, they were available in an oval, round, or rectangular shape and came in three different sizes.

More about this found via this Substack.

7. If you ever feel like you don’t finish things, take comfort with this Wikipedia list of “unrealised projects by artist”

Found here.

8. A Halloween Game for the family

Part of an old U.S. Halloween tradition, blindfolded children attempt to put out a candle in a photograph dated to the 1900s. (Try a Halloween quiz game.) The game, probably called “blow out the candle,” is often mentioned in early Halloween party books, Bannatyne said. Halloween in the U.S. was mainly a celebration for children until the premiere of the 1978 slasher flick Halloween, when the holiday “became paired with contemporary horror,” she added. This new association with bloody violence—and the attendant gory costumes and decorations—”opened up the holiday for adults and older children to celebrate, [and] made [it] more popular.”

Found on National Geographic.

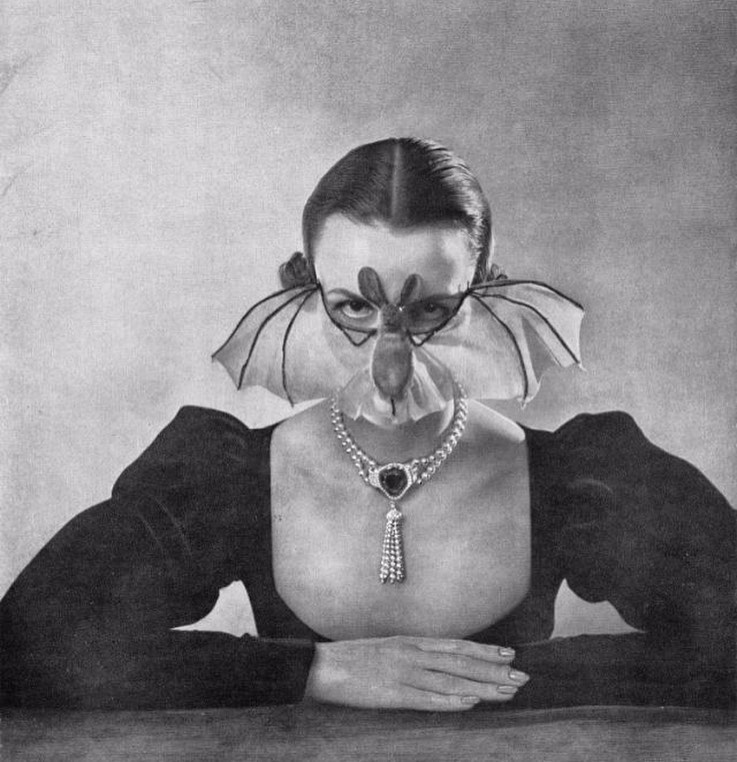

9. Art Nouveau Halloween Fashion

‘Bat’ necklace ca.1900, made of silver and pearls.

Evening bag, Lacloche frères, 1905.

Art Nouveau comb in the form of a bat with a female figure, ca.1900, Paris, France.

Found on Treasure Trove of Vintage Pleasures.

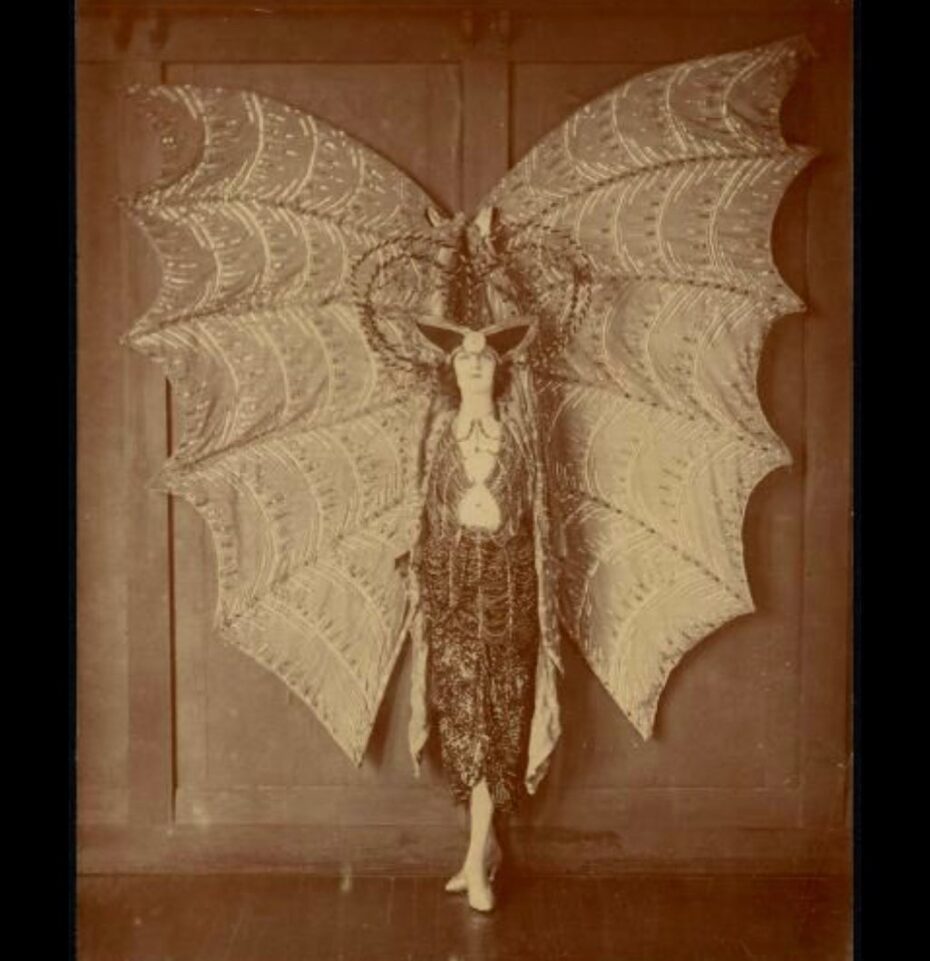

10. Bat Costumes (all Pre-Batman)

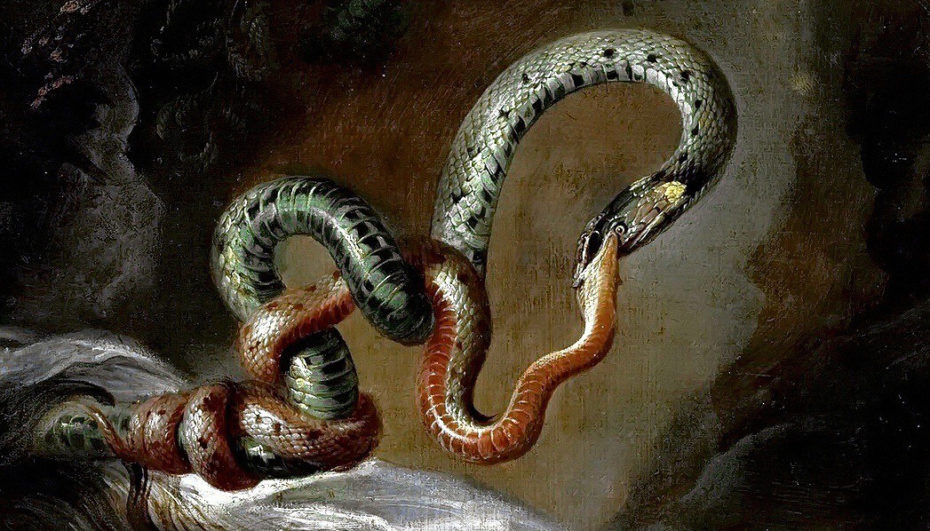

11. Head of Medusa painted by Peter Paul Rubens circa 1618

Scroll past quickly if you’re rather not see the close-ups:

The snakes in the painting have been attributed to Frans Snyders. It is in the collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Another version is held in Moravian Gallery in Brno.

Found on Wikipedia.

12. A historic spiritual sanctuary of miniature shrines on Kauai

Originally the site of an ancient heiau, or Hawaiian temple, the 32-acre valley on Kauai’s southern shore later became host to iconography of another religion: 88 Buddhist shrines. Measuring no larger than a dollhouse, the series of sacred monuments were built by Japanese émigrés in 1904; each one pays homage to its larger archetype along a 1,000-mile pilgrimage in Shikoku, Japan.

In the 1960s, Lawai’s miniature shrines became neglected and began to crumble. For decades they sat in disrepair as trees, grass and vines encroached upon them. Visitors to the center are invited to tour the rehabilitated shrines during a quiet, contemplative hillside walk.

More found here.