by Carol A Westbrook

This is the story of a DNA mutation that profoundly changed the course of human history, and had a major impact on human activities, altering communication, transportation, agriculture, and warfare. This story is about the horse, and how came to be a domesticated, rideable animal due to this DNA mutation. This genetic change in the horse occurred unexpectedly late, about 4500 years ago, which is almost 5000 years later than the domestication of pigs, cattle, goats and sheep.

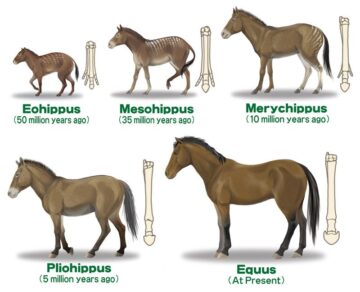

The earliest ancestors of horses, known as Eohippus, first appeared in North America about 55 million years ago, where they evolved into Equus, the modern horse ,by the time of the Pleistocene epoch. They spread from North America to Asia and Europe by crossing the Bering land bridge at a time when the oceans were much lower than they are today, that is during the last ice age. As Eohippus evolved into the horse as we know it today, it continued to be an important source of meat for the humans, and was hunted throughout the Pleistocene epoch (ice age).

The North American horse went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, about 10,000 years ago, along with most of North America’s large mammals. This period of extinction is known as the Pleistocene megafauna extinction event, and resulted in the loss of mammoths, mastodons saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, giant ground sloths and giant beavers. The cause of the extinction included climate change—the earth warmed up—over-hunting, change in flora resulting from climate change and the appearance of bison which competed directly with horses for food.

The horse disappeared from North America, but survived in Europe and Asia, particularly the Eurasian Steppes. No longer merely hunted, horses were raised in herds, and depended on grazing for sustenance. Horse are highly social animals that instinctively prefer to live in herds; they are well-adapted to severe winters and can graze year round, even through snow, unlike cattle, sheep and goats, which require winter fodder. The earliest shepherds, 5500 years ago, raised them for meat and milk, as they raised their sheep and goats.

It was known that horse domestication began about 4500 years ago, in the western Russian Steppes, but the exact chronology of horse domestication and its distribution around the world remained highly debated. A research team gathered an extensive collection of horse archeological remains spanning the Eurasian continent, and combined radiocarbon dating of this material with DNA genome sequencing to characterize a comprehensive genome time series. The work was coordinated by Ludovic Orlando, director of the Centre of Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse (CAGT, CNRS/Université Paul Sabatier), and involved 133 researchers from 113 institutions around the world.

These scientists reported that about 5,000 years ago, during the early stages of horse domestication, selective breeding favored a locus associated with the ZDPM1 gene; this gene is known to be a behavior modulator in mice and apparently it has the same effect in the horse. Horses with the ZDPM1gene were significantly tamer than wild horses; this character trait was highly desirable in pastoral herds and was selectively bred into them.

Then about 250 years later, a fortuitous mutation in the GSDMC locus in a ZDPM1 horse resulted in an animal which was stronger, with a change in the spinal anatomy that supported riding or carrying heavier loads on their backs. Its is likely that this mutation occurred only once. This horse variant was recognized to be so valuable that the characteristics were quickly assimilated into the horse population through selective breeding. Within just a few hundred years this variant surged from 1% to almost 100% of horses globally. The result was a rapid change in the dominant horse phenotype from a tame source of food, to one that supported riding or carrying heavier loads on their backs.

Recently, Liu and colleagues studied the effect of the GSDMC gene mutation by implanting it in mice. They found that GSDMC locus shapes spinal anatomy and locomotor traits, affecting both motor coordination and forelimb strength. In horses, the same locus is associated with structural back changes and increased endurance, resulting in horses with enhanced locomotor capacity, facilitating increased human mobility and speed of travel. Ironically, other variants of this same gene in humans are associated with chronic back pain and intervertebral disc problems; it has also been linked to sciatica.

It was the lower Don-Volga steppes—southern Russia, just above the Caspian Sea—where these modern, rideable horses first emerged, about 4200 years ago (2200 BCE). It didn’t take long for the nomadic peoples of the steppes to incorporate the horse into their lifestyle. Rather than herding horses as a food source, the shepherds rode the horses and used them to herd other animal stocks, such as goats and sheep. Horses were also used for transportation, as the nomads traveled the steppes. This lifestyle still persists today in Mongolia, where one can find nomadic herder communities who rely primarily on horses for transportation and herding.

It is not surprising that the first use of horses in warfare came from the nomadic tribes of the open steppes who formed bands of fierce mounted archers. A confederation of these tribes, called The Xiongnu, formed the first major empire on the Eurasian steppes, from 200 BCE to 100 AD. The Xiongnu were frequently in conflict with the Han dynasty in China, who built the Great Wall of China in response, and eventually defeated them. The emergence of the Xiongnu marked a turning point in human history, as equestrianism became foundational to warfare. The Xiongnu influenced later nomadic empires like the Mongols and contributed to significant geopolitical shifts, including the decline of the Roman Empire

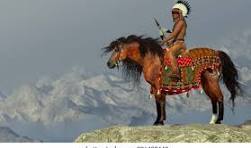

These horses spread rapidly across Eurasia, reaching the furthest corner by 3000 years ago. The horse made possible long-distance voyages for trade, and graves of Xiongnu revealed such treasures as Roman glass, Persian textiles, and Greek silver. The introduction of the domesticated horse made the world smaller, not unlike the introduction of the airplane. It revolutionized transportation, agriculture, and warfare through technologies like the chariot, saddle, and stirrup. It also fostered increased trade and cultural exchange, led to the rise of powerful horse-based empires, and dramatically altered the ecology and social structures of many regions. The introduction of the domesticated horse to the New World has been attributed to Cortés in 1519, during his campaign again the Aztec Empire, though several other Spanish explorers also brought horses about the same time. Escaped or released horses quickly adapted to the wild, thriving in environments that had once been their homeland before their extinction at the end of the last ice age. These feral horses dispersed into areas from the American Southwest up through the Great Plains and into  the northern Rocky Mountains. Many were captured and integrated into indigenous communities, transforming their lifestyles, economies and warfare, in particular the bison-hunting Indians of the great plains. Many of the indigenous populations of North America and parts of South America already had integrated the horse into their cultures before contact with Europeans. The horse, which began in North America, has finally returned to its home

the northern Rocky Mountains. Many were captured and integrated into indigenous communities, transforming their lifestyles, economies and warfare, in particular the bison-hunting Indians of the great plains. Many of the indigenous populations of North America and parts of South America already had integrated the horse into their cultures before contact with Europeans. The horse, which began in North America, has finally returned to its home

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating no