Powerful Native American Images

A century ago, cameras documented Native American men as leaders, healers, warriors, and elders. Their faces, once obscured by time, return in sharp detail. Each photograph speaks to a moment when Native American men and women balanced cultural continuity with immense change.

Chief Joseph Of The Nez Perce

Chief Joseph, photographed by Edward Curtis in the early 1900s, was already legendary for leading his people during the 1877 Nez Perce War. His portrait highlights his dignity and reminds viewers of his calls for peace and justice.

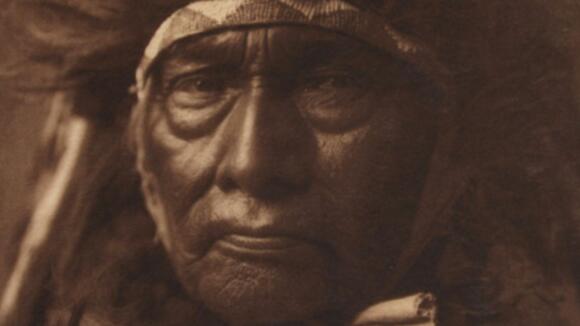

Navajo Medicine Man

Medicine men were respected in the Navajo Nation. Their role extended beyond healing as they were the keepers of ceremonies and chants central to Navajo identity. This rare portrait offers a glimpse into traditions threatened by assimilation policies of the early 1900s.

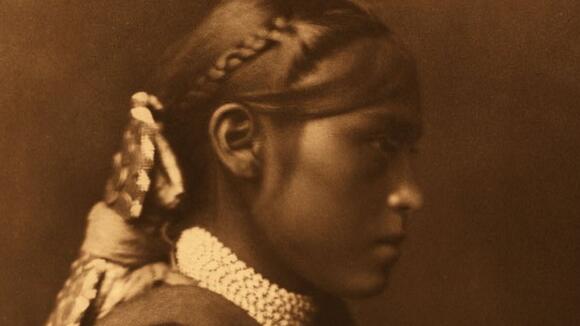

An Apsaroke Warrior

Curtis photographed Lone Tree of the Apsaroke (Crow) in 1908. His profile emphasizes sharp features and eagle feathers, symbolizing both individuality and collective heritage. The Apsaroke were noted for their horsemanship and warrior culture, and this portrait preserves an intimate moment of identity.

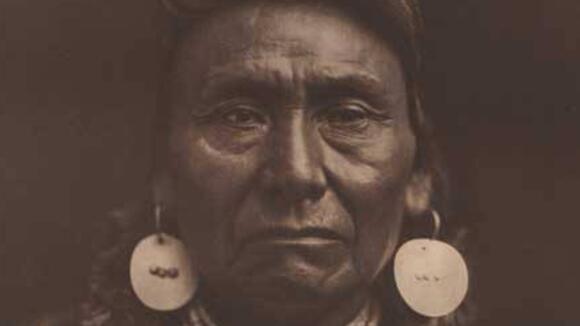

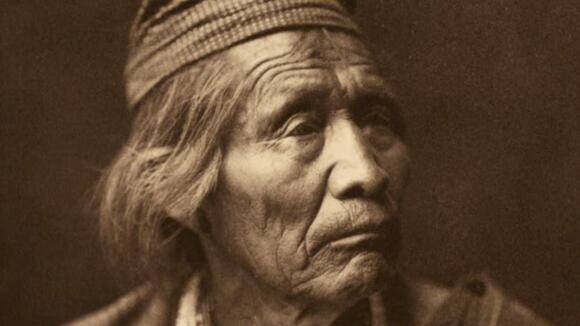

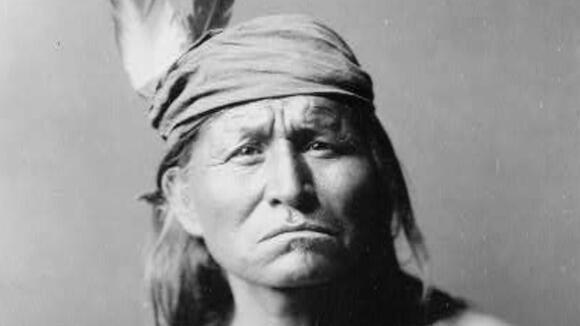

Jicarilla Man

This sepia-restored 1904 portrait by Edward S Curtis captures a Jicarilla Apache man, dignified yet introspective. Draped in a traditional blanket and wearing minimal adornment, the subject bridges a moment between ancestral tradition and modern pressures.

Sioux Hunters And Chiefs In Curtis’s Vision

Early 1900s images of Sioux leaders and hunters convey presence and solidarity. Feathered headdresses and animal hides reflect ceremonial symbolism, while their collective stance shows unity. At a time when US policies sought assimilation, photographs like this preserved a visual record of leadership and cultural heritage.

Navajo Leader

Curtis’s 1904 photograph of a Navajo leader presents strength in stillness, with the subject wearing traditional adornments. Such images were recorded during a period of cultural pressure, yet they preserve visual testimony of Navajo sovereignty and identity in the American Southwest.

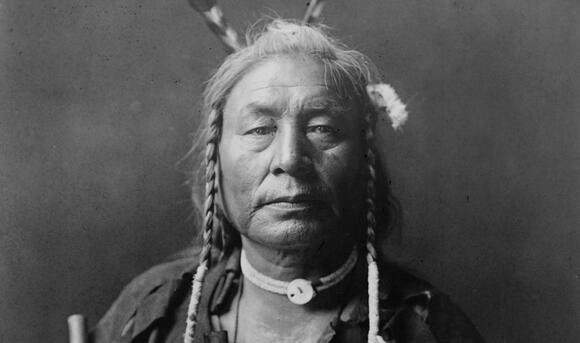

A Crow Tribal Leader

Photographed in 1908, Bull Chief of the Crow Nation sits in full regalia. His gaze and elaborate feather headdress demonstrate individual prestige and collective cultural expression. This was an attempt to record leaders at a time when tribal authority was shifting under federal assimilation policies.

Mandan Men Overlooking The Missouri River

In this image, Mandan men are seen observing the sweeping Missouri River valley, once central to their people’s trade and agricultural life. The image’s setup highlights how the environment shaped Mandan society.

Mandan Hunter With Buffalo Skull

Buffalo played an important role in Plains traditions. In this photo, a Mandan hunter is photographed with a buffalo skull that represents and celebrates the cycles of life. Taken around 1909, the image reflects the resilience of Mandan spiritual practices despite decades of upheaval and ecological transformation.

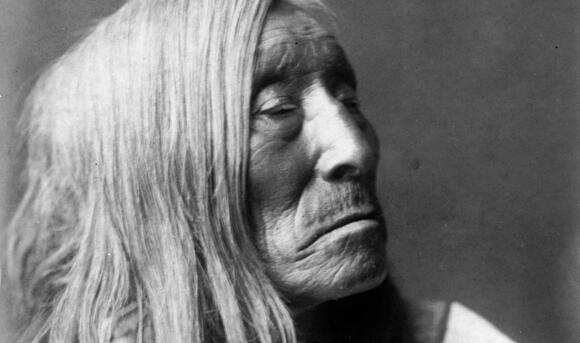

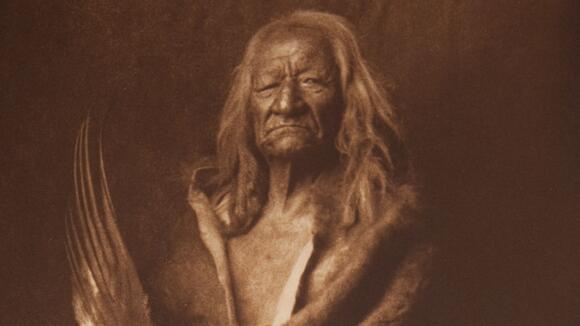

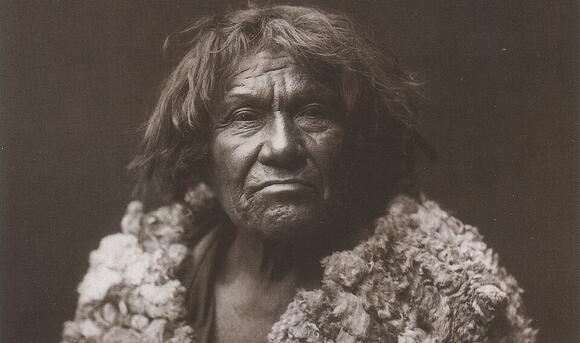

A Mandan Elder

Crow’s Heart, a Mandan man, was documented by Curtis in the early 1900s. His calm expression and traditional clothing reveal dignity amidst change. Mandan communities, long established along the Missouri River, faced epidemics and displacement, but portraits like this preserved cultural presence.

Apsaroke War Group On Horseback

This photograph from 1905 portrays three Crow horsemen—Uphaw, Which Way, and Packs The Hat—mounted in full gear. Their arrangement conveys readiness and solidarity, reflecting the Crow’s famed equestrian culture. Such images highlight warrior traditions.

Atsina Fly Dance Ceremony

Taken in 1908, Curtis’s photograph of the Atsina Fly Dance shows men kneeling around a feather-crowned staff. The ritual represented renewal and connection to the spiritual world. It reflects the ceremonial richness of the Gros Ventre and preserves traditions that might otherwise have been lost amid assimilationist pressures of the time.

Awaiting The Scouts’ Return

Scouts carried important news, and this 1908 photo shows Atsina men and their horses poised on a ridge, waiting for them. The elevated vantage suggests anticipation and vigilance, echoing the importance of scouting in protecting communities. This image captures military readiness and the symbolic role of watchfulness in Plains survival.

On The War Path

Depicting a mounted band in 1908, Curtis’s “On The War Path” conveys ceremonial strength rather than active battle. The regalia signals warrior identity while emphasizing group cohesion. The photograph illustrates how traditional displays of readiness remained integral to cultural memory during a period of dramatic change.

Incense Ceremony Atsina 1908

Atsina rituals were recorded in images like this one, where one man’s arm is raised as smoke rises. The scene highlights the sacred role of incense in connecting participants with the spiritual realm. Such ceremonies preserved cultural continuity, reinforcing bonds between individuals, ancestors, and natural forces.

Oraibi Snake Dance Hopi 1904

The Hopi Snake Dance, photographed by Curtis around 1904, takes place before pueblo walls crowded with onlookers. The ritual, tied to rainmaking and harmony with nature, blends performance with sacred meaning. Public ceremonies reinforced Hopi identity and spirituality in the face of mounting external scrutiny.

Horse Capture Atsina C

This evocative half-length portrait from Curtis’s Atsina series (circa 1908) shows a man in mid-gesture. He is shown in traditional attire and ornaments with the barrel of a modern rifle on the left. The image sheds light on a transitional phase in the lives of the Atsina people.

Black Eagle An Assiniboine Man

Black Eagle of the Assiniboine Nation was photographed in the early 1900s. His composed stance and traditional regalia represent endurance amid widespread upheaval. This portrait preserves his likeness and records cultural markers of identity.

A Piegan Leader

Curtis’s portrait of a Piegan man, circa 1900, reveals ceremonial attire rich in symbolism. Every element—from eagle feathers to beadwork—carried spiritual and social meaning. The Piegan, part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, faced immense change during this period.

Apache Warrior Photographed In 1903

This 1903 portrait of an Apache man emphasizes strength in simplicity. His direct gaze and traditional adornments reflect the resilience of a people who resisted conquest longer than many tribes despite forced relocation and military campaigns.

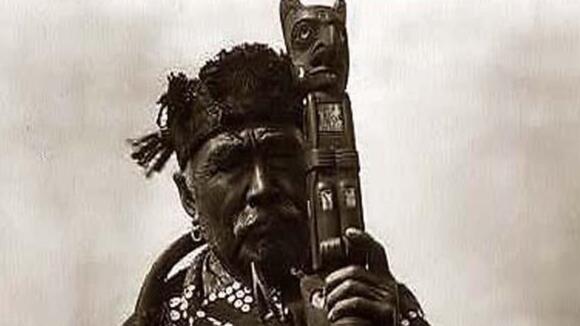

Kwakiutl Elder In Ceremonial Regalia

Hamasaka, a Kwakiutl elder, is photographed here in elaborate attire. The headdress and carved adornments reflect Pacific Northwest traditions where ceremonies and masks held spiritual weight. Such documentation provided rare records of coastal cultures.

Delegate Portrait By DeLancey Gill

Around 1900, DeLancey Gill photographed Native delegates in Washington, DC, including leaders such as Chief Joseph. These formal studio portraits highlight the dual roles of Native leaders as community representatives and negotiators with federal officials.

An Atsina Warrior

Filled with dignity, Curtis’s photograph of Eagle Child from 1908 presents a half-length portrait. His attire blends practicality with ceremonial details and markers of identity for the Atsina, or Gros Ventre. By capturing individuals like Eagle Child, Curtis created a permanent record of lives shaped by cultural tradition and change.

Native American Man Photographed In 1903

Although the man in the photo is unidentified, his image highlights the strength of Native presence at the dawn of the 20th century. The subject’s features and attire represent continuity amid transition. Such portraits were often generalized in archives, yet they remain vital reminders of individuality within broader cultural narratives.

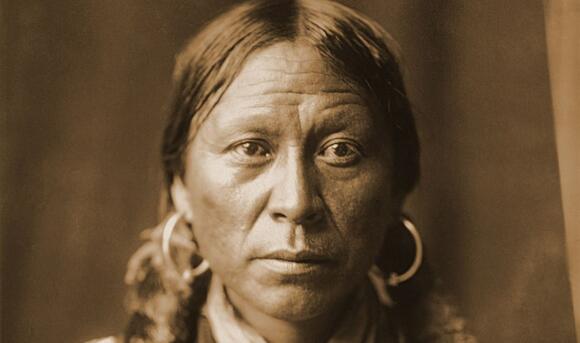

Sigesh An Unmarried Apache Woman 1905

Curtis photographed Sigesh, an unmarried Apache woman, in 1905. Her portrait offers rare documentation of women within his collections. The photograph highlights traditional attire and youthful expression, preserving a record of gender roles and identity at a time when assimilation policies threatened cultural continuity.