Long before modern society began challenging ideas about gender and sexuality, the women of the Ouled Naïl tribe in Algeria lived by a set of values that gave them remarkable independence.

Long before modern society began challenging ideas about gender and sexuality, the women of the Ouled Naïl tribe in Algeria lived by a set of values that gave them remarkable independence.

They earned their own fortunes, chose their partners freely, and engaged in relationships outside marriage without shame. Far from being condemned, these choices were seen as vital contributions to the tribe’s social and economic life — a rare kind of freedom in a world still bound by strict moral codes.

The Ouled Naïl were an Amazigh (Berber) people who lived high in Algeria’s Atlas Mountains. Though they converted to Islam in the 7th century, they managed to preserve their distinct culture, traditions, and identity well into the 20th century.

Among their many customs, none became more famous than that of the Nailiyat — the women dancers whose art, beauty, and independence captured imaginations both at home and abroad.

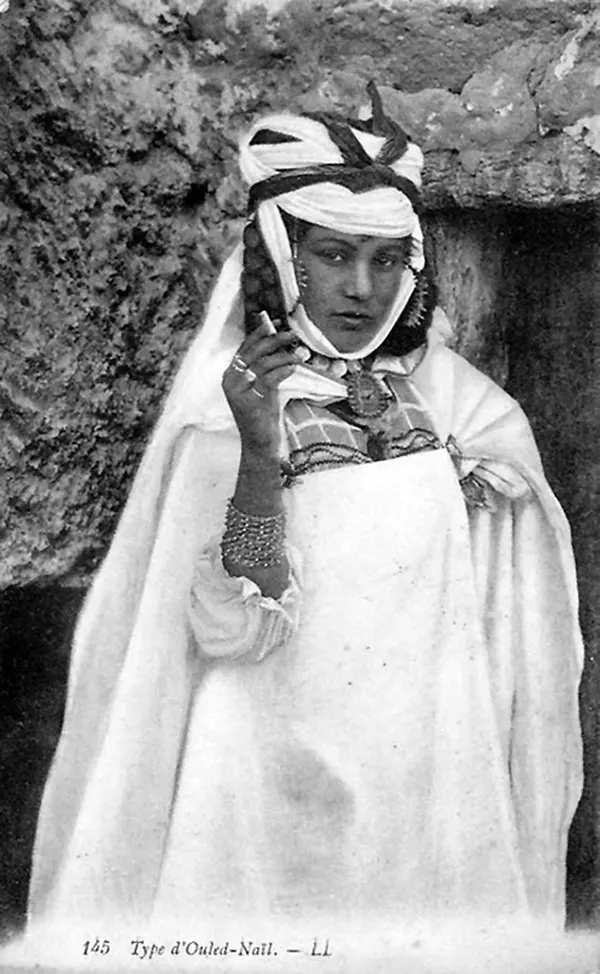

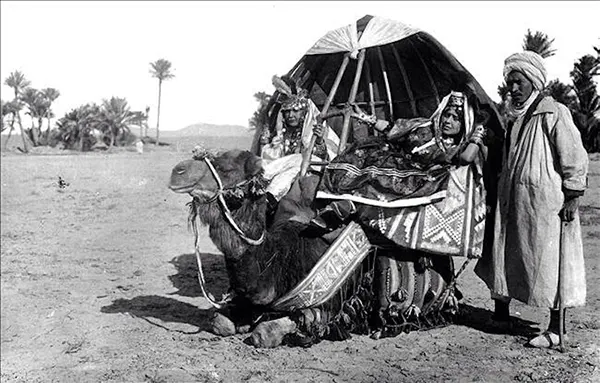

Ouled Nail tribe, Ernst Heinrich Landrock, Algeria, 1910s.

Each year, Nailiyat women left their mountain villages to travel to cities and oasis towns, where they worked as professional dancers and hostesses.

Not every woman from the tribe pursued this path, but those who did often learned it from their mothers and aunts. The dance and its accompanying customs were passed down like a family inheritance.

While women from neighboring tribes sometimes turned to dancing out of necessity — as widows or orphans — the Ouled Naïl embraced it as a proud tradition, one freely chosen and sustained through generations.

Many girls began performing as young as twelve, joining troupes that carried the reputation of their people far beyond the desert.

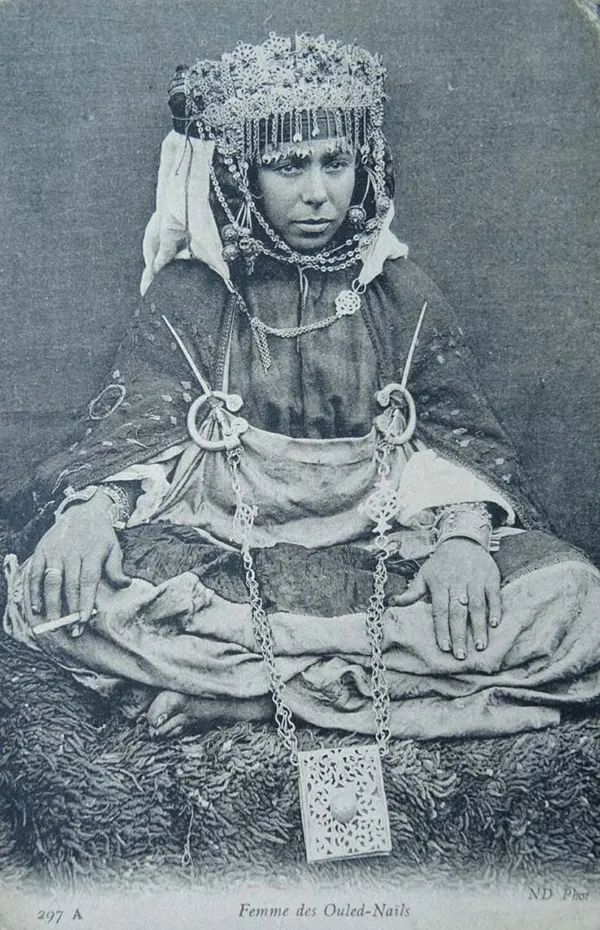

Two Nailiyat photographed by Rudolph Lehnert, 1904.

During these seasonal migrations, the men remained in their home villages, leaving the women to form tight-knit, female-led communities in the cities.

Older women managed the households and looked after the younger performers, creating an environment that was both protective and empowering.

Men entered these circles only as guests — as clients, lovers, or friends — but the center of this world always belonged to the women themselves. They set the rules, managed their earnings, and shaped a life defined by their own agency.

Visually, the Nailiyat were unforgettable. Draped in layers of colorful silk and rich fabrics, their long braids, hennaed hands, and intricate facial tattoos marked their tribal identity.

Visually, the Nailiyat were unforgettable. Draped in layers of colorful silk and rich fabrics, their long braids, hennaed hands, and intricate facial tattoos marked their tribal identity.

Heavy gold and silver jewelry, often crafted from the very coins they earned, shimmered around their necks and arms. Their headdresses and spiked bracelets served both as adornments and, when necessary, as protection.

But such visible displays of wealth also made them targets — many tales tell of dancers robbed or even killed for the treasures they wore.

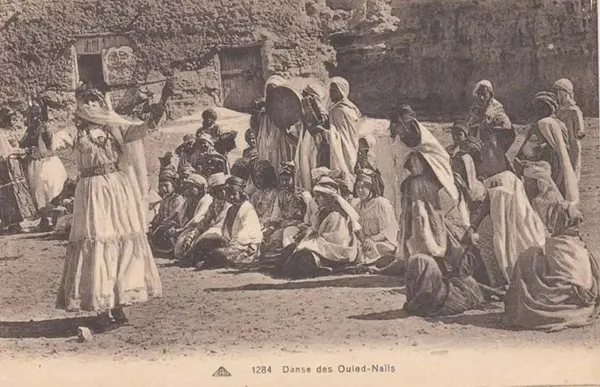

A group of Nailiyat photographed by Rudolph Lehnert, 1904.

Their performances were mesmerizing rituals of rhythm and control. Groups of dancers performed together, taking turns in the spotlight while others clapped, sang, or chanted in accompaniment.

A high-pitched zaghareet — a celebratory ululation — signaled the start. Movements were slow and deliberate: gliding steps, rhythmic hip rolls, heel taps that made their anklets sing, and fluid gestures that hinted at something both sacred and sensual.

Some dancers displayed astonishing physical mastery, isolating and vibrating muscles with precision. What began as a dance of grace evolved into an expression of power, confidence, and freedom.

Beyond the stage, the Nailiyat also entertained men in private settings — an arrangement resembling a refined form of patronage rather than prostitution.

Beyond the stage, the Nailiyat also entertained men in private settings — an arrangement resembling a refined form of patronage rather than prostitution.

Guests offered gifts or money in exchange for conversation, company, and hospitality, not for specific acts. The women decided for themselves how intimate such relationships became.

If a dancer chose a lover, he often showered her with additional gifts, but she remained entirely independent. Should she bear a child, the baby was welcomed into her family, with the birth of a girl celebrated as a blessing for continuing the lineage of strong women.

After several seasons, when a Nailiya had saved enough wealth, she returned home to her mountain village as a woman of means.

After several seasons, when a Nailiya had saved enough wealth, she returned home to her mountain village as a woman of means.

There she could purchase a home, live comfortably, and choose a husband for love rather than necessity. Within the Ouled Naïl, her past was not a source of shame but a mark of strength and accomplishment.

As one local man explained in Lawrence Morgan’s 1956 book Flute of Sand: “Our wives, knowing what love is, and having wealth of their own, will marry only the man they love. And, unlike the wives of other men, will remain faithful to death. Thanks be to Allah.”

The Ouled Naïl’s fame spread far beyond Algeria. Arab travelers spoke admiringly of their charm and artistry, and even the city of Bou Saada — closely linked to the Nailiyat — earned the nickname “Place of Happiness” in their honor.

The Ouled Naïl’s fame spread far beyond Algeria. Arab travelers spoke admiringly of their charm and artistry, and even the city of Bou Saada — closely linked to the Nailiyat — earned the nickname “Place of Happiness” in their honor.

When French colonizers arrived in 1830, they too were captivated. European artists and photographers filled salons with Orientalist paintings, postcards, and photographs of these mysterious women, adorned in glittering jewelry and coins.

Yet this fascination came at a cost. The colonial lens distorted what it captured. Rather than seeing the Nailiyat as artists and entrepreneurs within a complex matriarchal culture, the French reduced them to exotic curiosities and conflated them with prostitution — a label that stripped away their dignity and misunderstood their traditions.

Yet this fascination came at a cost. The colonial lens distorted what it captured. Rather than seeing the Nailiyat as artists and entrepreneurs within a complex matriarchal culture, the French reduced them to exotic curiosities and conflated them with prostitution — a label that stripped away their dignity and misunderstood their traditions.

The very images that brought the Ouled Naïl international fame also contributed to their exploitation and the erosion of their way of life.

Many of the vintage postcards that survive today were not candid portraits but carefully staged productions designed to satisfy European fantasies of the “Orient.”

Many of the vintage postcards that survive today were not candid portraits but carefully staged productions designed to satisfy European fantasies of the “Orient.”

Algerian anthropologist and dancer Amel Tafsout noted that these images deliberately contrasted the Ouled Naïl with “respectable” European women, reinforcing colonial ideas of cultural superiority.

By the time Algeria gained independence in 1962, more than a century of occupation and nearly a decade of war had devastated the Ouled Naïl way of life. The new government’s push for assimilation further erased what remained of their nomadic traditions.

By the time Algeria gained independence in 1962, more than a century of occupation and nearly a decade of war had devastated the Ouled Naïl way of life. The new government’s push for assimilation further erased what remained of their nomadic traditions.

Though the Nailiyat dancers have vanished, their legacy endures — in photographs, stories, and the faint echoes of music that once drifted across the desert night.

Young Ouled Naïl woman circa 1905.

Ouled-Naïl woman from Alegria by Pascal Sebah, 19th century.

Ouled Nail Bracelet.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Upscaled by RHP).