When most people think of Native American warriors on horseback, they picture the Comanche thundering across the Great Plains. Yet these legendary horsemen harbored secrets that would astonish even the most devoted history buffs. The Comanche didn’t just ride horses – they transformed the entire landscape of warfare, culture, and survival in ways that still echo today.

Their story goes far beyond the typical narratives of conquest and defeat. These remarkable people developed innovations so sophisticated that modern military strategists study their tactics, while their horse-breeding techniques influenced bloodlines that continue to this day. From childhood training methods that would seem impossible to adult warriors who could shoot twenty arrows in the time it took a soldier to reload a musket, the Comanche mastered skills that redefined what it meant to be a mounted culture. Let’s dive into the most startling truths about these extraordinary masters of the plains.

Children Began Riding Before They Could Properly Walk

The Comanche started their legendary horsemanship training at an age that would make modern parents gasp – children as young as four or five years old were given their own ponies, with some sources indicating boys learned to ride before age six. This wasn’t casual riding lessons but intensive daily training that would shape their entire identity.

Boys drilled with their horses every single day, starting with picking up small, lightweight objects off the ground while riding at gradually increasing speeds, eventually progressing to retrieving larger and heavier items, and ultimately learning to pick up a human body from the ground while galloping – a skill considered invaluable during battle. The intensity of this training created riders whose abilities seemed almost supernatural to outside observers.

They Could Fire Twenty Arrows While a Soldier Reloaded Once

Comanche warriors possessed such extraordinary speed and accuracy that they could fire multiple arrows rapidly while a soldier reloaded and fired a single musket. This gave them an overwhelming advantage in combat that European and American forces struggled to counter.

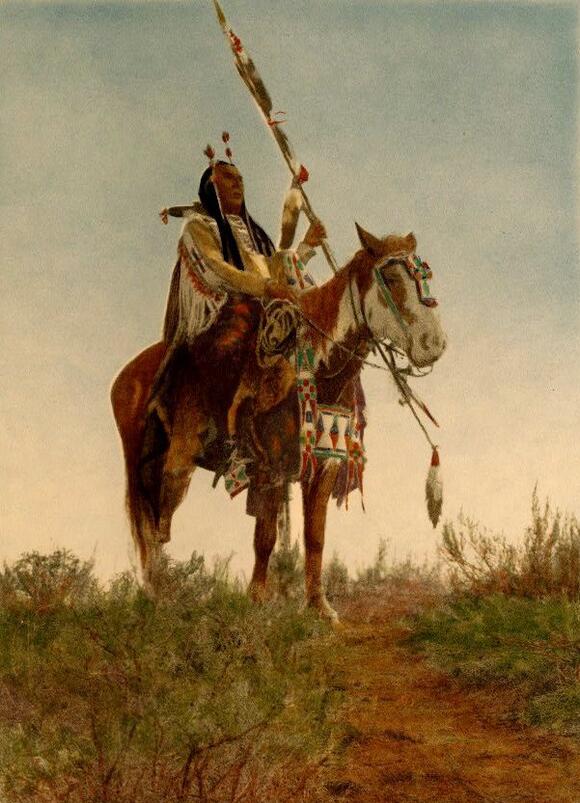

All Comanche warriors mastered the technique of dropping to the side of their galloping horse, hanging with one heel over the back and one arm looped in a braided sling on the mane while loosing numerous arrows during the time it took a soldier to load his musket, with each arrow capable of killing a man at thirty yards – all while carrying a shield and a fourteen-foot lance. Their archery skills weren’t just about speed but deadly precision that made them formidable opponents even against firearms.

Their Most Famous Battle Maneuver Was Considered Physically Impossible

Artist George Catlin witnessed a Comanche feat of horsemanship that “astonished me more than anything of the kind I have ever seen, or expect to see, in my life” – a stratagem where warriors could drop their body upon the side of their horse while passing at full speed, hanging in a horizontal position behind the horse’s body with their heel over the horse’s back, all while wielding their bow, shield, and fourteen-foot lance.

These warriors rode bareback at breakneck speed, dodging enemy fire by hugging the flanks of their steeds and shooting with bow and rifle on the ride, circling and weaving over the contours of the land before dissolving into the sweeping grasslands – tactics that confounded and enthralled the U.S. Cavalry in equal measure. This maneuver wasn’t just showmanship but a deadly effective combat technique that protected the warrior while maintaining offensive capability.

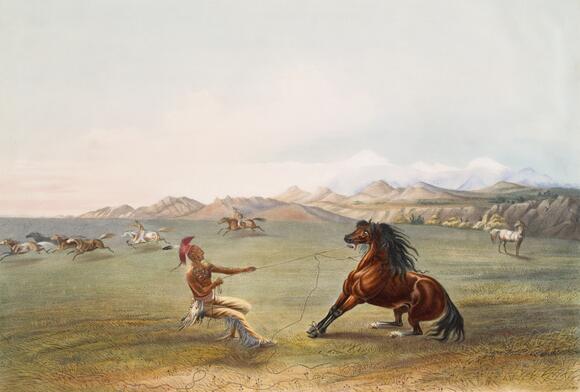

They Developed Revolutionary Horse-Breaking Methods

The Comanche technique of breaking wild horses amazed observers: they would lasso a wild horse, tighten the noose to choke it to the ground, then slack the rope to give it air back while stroking the horse gently all over its head and neck and breathing into its nostrils to bond with it, finally mounting and riding away as the horse became comfortable with its new partner.

They often broke horses in soft sand or water to avoid agitating the animals, using patient and gentle methods that focused on creating a bond with their horses rather than using brute force. This approach produced horses that were not just broken but genuinely cooperative partners, creating the deep horse-human bonds that made their cavalry tactics so effective.

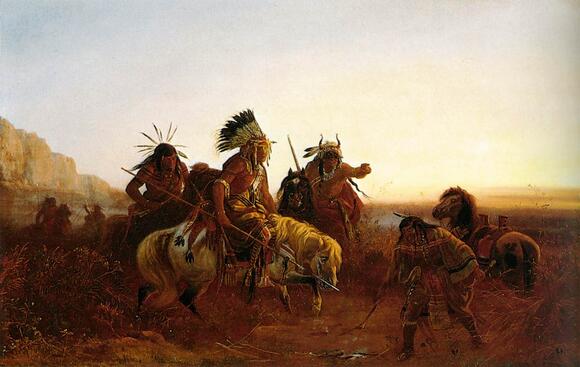

A Single Warrior Could Own Hundreds of Horses

Wealthy Comanche warriors could own dozens of horses, while prominent chiefs might possess hundreds – compared to a Sioux chief who might have forty horses. This massive accumulation of horses wasn’t just about wealth but represented mobile power on an unprecedented scale.

Their horse-capturing skills were equally impressive – witnessed accounts describe how they could drive wild horse bands into deep ravines where dozens of riders waited with lariats, capturing entire herds in elaborate ambushes, with one account noting that only one horse escaped from a hundred-animal capture, and that single escapee was retrieved within two hours and returned “tamed and gentle”. Their ability to manage such enormous herds gave them logistical advantages that European military strategists struggled to comprehend.

Women Were Equally Skilled Riders and Warriors

Even Comanche women were described as “daring riders and hunters, lassoing antelope and shooting buffalo”, breaking the stereotype that only men mastered horsemanship among Plains tribes. Both men and women developed equally notable abilities in riding, with women being poised and gifted riders who could move belongings, children, and the elderly from camp to camp on horseback.

Women played vital roles in Comanche society beyond domestic duties – they were responsible for raising children, processing food, and crafting clothing and shelter, but some women also participated in warfare and held positions of influence in the tribe. Their equestrian skills made them valuable contributors to the mobile lifestyle that defined Comanche culture, proving that mastery of the horse wasn’t limited by gender in this remarkable society.

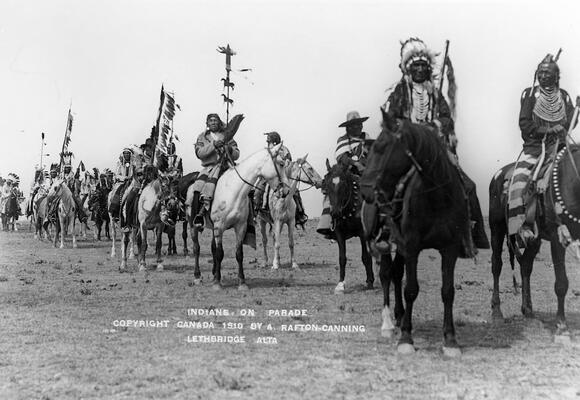

They Created the First “Horse Nation” in North America

The Comanche, originally a branch of the Shoshone, began their transformation into a “Horse Nation” in the early 18th century after acquiring horses through trade and raids, quickly realizing the advantages they offered for hunting, warfare, and transportation, and were among the early Plains Indians to master horse culture.

The arrival of horses – called “Sunka Wikan” or “the sacred dog” – profoundly influenced indigenous life in formative ways, enabling fast and effective combat, transportation and hunting while impacting ecological relations and spatial sensibilities, providing what one historian called “a heady feeling of suddenly widening potential”. Their horse culture became so influential that it spread throughout the Plains, fundamentally changing Native American life across the continent.

Their Horse-Breeding Programs Were More Advanced Than European Methods

The Comanche were masters of horse breeding who selected only the strongest and most agile animals for their herds, understanding equine behavior and developing unique training techniques, with Comanche known to breed only the most fast and responsive stallions as studs. Their scientific approach to breeding created horses perfectly adapted to their needs.

They carefully selected their breeding stock to create horses that were fast, agile, and resilient, specifically suited to their needs for hunting and warfare, breeding with remarkable specificity for their exact requirements. Their expertise became so renowned that they began supplying horses to French and American traders, dominating the Texas Panhandle area and becoming the premier horse suppliers for the region. This economic dimension of their horse mastery gave them significant trading power and diplomatic influence across the frontier.

The Comanche’s mastery of the horse represented far more than simple riding skills – it was a complete reimagining of what human-animal partnership could achieve. Their innovations in training, breeding, warfare, and daily life created a culture so effective that it dominated the Great Plains for over a century. Though their traditional way of life ultimately succumbed to overwhelming military pressure and the destruction of the buffalo herds, their legacy lives on in modern horsemanship techniques, military tactics, and the enduring image of the mounted warrior that continues to capture imaginations worldwide. What other “impossible” achievements might we discover when we dig deeper into the stories of remarkable cultures? The Comanche remind us that human potential often exceeds our wildest expectations.