Before police databases and mugshots, the Wild West relied on paper and ink to spread the word about outlaws, fugitives, and missing people. “Wanted” posters were nailed to saloon doors, post offices, and courthouse walls, offering rewards that tempted bounty hunters and ordinary citizens alike. These real historical posters show the faces and names that once made headlines across 19th-century America. From signature forgers to the man who took Abraham Lincoln’s life, these were some of the most infamous “wanted” posters of the Old West.

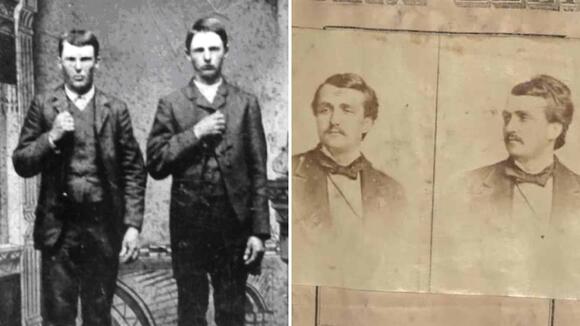

#1: A $100 reward offered for a dark-skinned man named Abram fleeing from Culper County

Notices like this were a common sight in American newspapers during the early 19th century. Enslavers often placed ads offering money for the capture of people who had escaped bondage, describing them in detail to make identification easier. The reward of $100 was a large sum at the time, showing both how valuable enslaved labor was to owners and how determined they were to maintain control over human lives.

This ad for Abram’s capture reflects the painful history of slavery in America, where freedom-seeking men and women risked everything to escape. Such documents now serve as stark reminders of the personal cost of slavery and the courage of those who fled toward uncertain freedom. They also help historians trace names and stories that were once meant to be erased or forgotten.

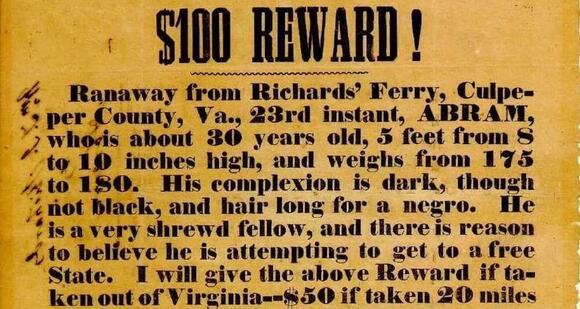

#2: A $1000 reward poster for John Hunt Morgan after escaping Ohio Penitentiary in 1863

Confederate cavalry officer John Hunt Morgan was one of the most daring figures of the American Civil War. Known for his fast-moving raids deep into Union territory, Morgan’s men disrupted railways, communication lines, and supply routes. After being captured in Ohio, his imprisonment was seen as a major victory for the Union.

When Morgan escaped from the Ohio Penitentiary in 1863, the news spread quickly through the divided nation. A $1,000 reward was a large bounty, reflecting the Union’s urgency to recapture him. Though his later raids were less successful, Morgan became a symbol of Southern resistance and a legendary figure in postwar Confederate memory.

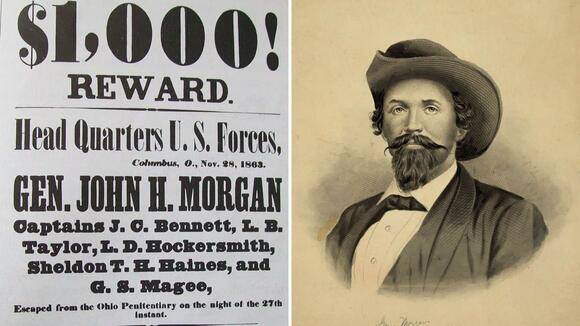

#3: $5000 reward for the capture of N. Appleton Shute in 1873

The late 19th century saw a wave of financial crimes as America’s economy expanded and banking systems matured. N. Appleton Shute was wanted in 1873 for charges tied to embezzlement and fraud—a crime that struck at the heart of growing public distrust in new financial institutions. Posters like this were circulated across state lines to aid his capture.

A $5,000 reward was an extraordinary sum at the time—equivalent to more than $100,000 today—showing the seriousness of the offense. Reward posters like this not only sought justice but also served as a form of public warning, reminding citizens that even in the modernizing 1870s, law enforcement still depended on community vigilance and cooperation.

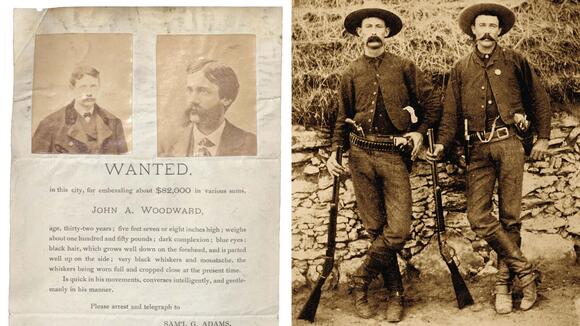

#4: Wanted poster for John A. Woodard, a 32-year-old man who embezzled $82,000

During the Gilded Age, when wealth and speculation defined the American economy, white-collar crimes like embezzlement became increasingly common. John A. Woodard’s case involved an enormous theft—$82,000 was a staggering amount of money in the late 19th century, capable of ruining entire companies or banks.

Posters like this reflected the rise of an interconnected economy where fugitives could easily cross borders by train or ship. The professional appearance and detailed description highlight how law enforcement adapted to track financial criminals. Woodard’s pursuit showed that crime in the age of industry wasn’t limited to guns and stagecoaches—it had moved into the boardroom.

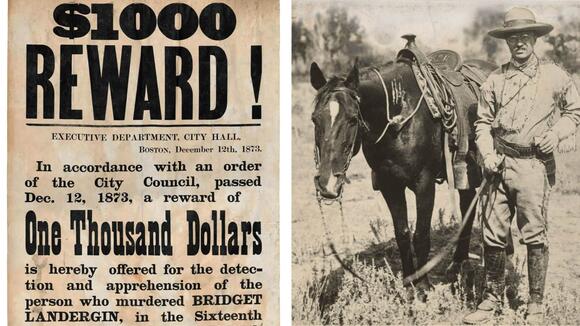

#5: A $1,000 reward for whoever took the life of Bridget Landergin

Violent crimes in small American towns often captured national attention in the late 1800s, when communities still relied on printed broadsides to spread news. The murder of Bridget Landergin shocked residents, and local authorities quickly offered a $1,000 reward—an extraordinary sum that underscored both the brutality of the act and the desperation to find the killer.

The Landergin case exemplifies how 19th-century law enforcement depended on public participation and print communication. Before the rise of modern forensic methods, justice often rested on rumor, community pressure, and the promise of cash rewards. These posters reveal a time when solving crime was as much a social effort as a legal one.

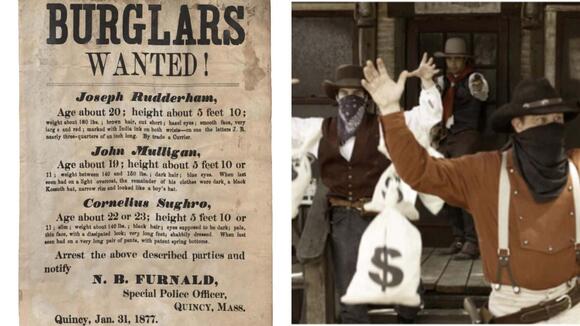

#6: Wanted posters for burglars Joseph Rudderham, John Mulligan, and Cornelius Sughro from 1877

By the late 1870s, the growth of American cities brought both opportunity and crime. Burglary became one of the most common urban offenses as new wealth and goods filled homes and businesses. Joseph Rudderham, John Mulligan, and Cornelius Sughro were typical examples of small-time criminals whose offenses drew local attention and public warnings.

Wanted posters like this were printed by the hundreds, pinned up in saloons, train depots, and post offices. They relied on facial descriptions, distinctive marks, and aliases since photography was still expensive and rarely used in smaller cases. The three burglars’ listing captures a moment when policing was becoming more organized, but still deeply dependent on local vigilance and printed alerts.

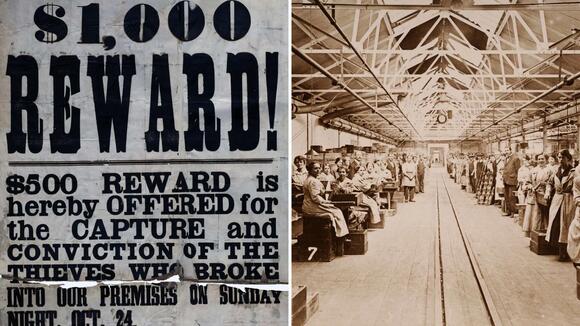

#7: $500 reward offered for capturing and convicting the thieves who broke in and stole property from Henry Morgan & Co. on Oct. 24, 1875

Henry Morgan & Co. was one of the major department stores of its day, part of a new retail model that drew crowds to urban centers. When the store was burglarized in 1875, it wasn’t just a loss of merchandise—it was a symbolic challenge to a growing consumer culture built on trust and spectacle. The $500 reward represented both outrage and determination to preserve that trust.

Public notices like this made it clear that major retailers saw theft as a threat to their modern image. Offering payment only upon conviction also reflected how much store owners valued legal closure over mere recovery of goods. It’s a small window into how businesses in the 19th century worked to professionalize both their image and their security.

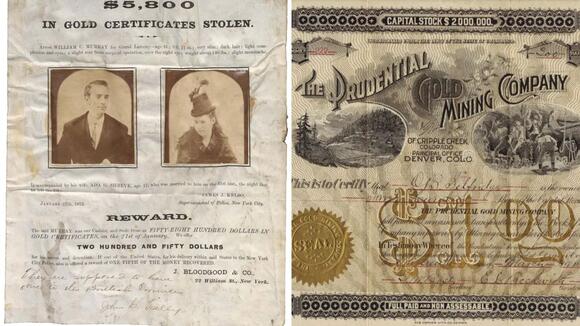

#8: $250 reward for capturing a couple of thieves who stole $5,800 worth of gold certificates

Gold certificates were a relatively new form of paper currency in the 19th century—notes backed directly by the U.S. Treasury’s gold reserves. Stealing them was a lucrative but risky crime, since the numbers could easily be traced. When thieves made off with $5,800 worth, it represented a serious blow, both financially and symbolically, to the stability of the young national banking system.

The $250 reward emphasized the federal and local authorities’ determination to recover the stolen notes. This poster also reflected the growing sophistication of financial crimes in post–Civil War America, where currency and credit were replacing hard coin—and criminals, too, were adapting to the modern economy.

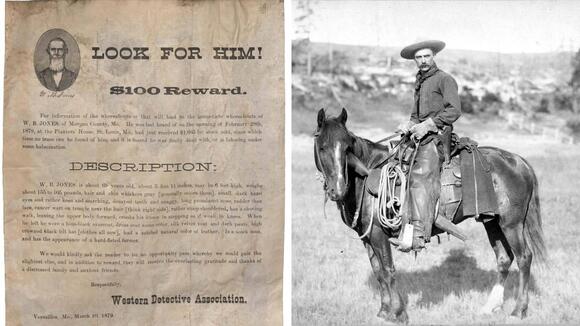

#9: $100 reward for information on the whereabouts or information that would lead to the capture of W. B. Jones of Morgan County, Montana in 1879

In the rugged territories of the American West, fugitives like W. B. Jones could disappear for months or even years. Montana in 1879 was still largely frontier, where communication and law enforcement depended on scattered telegraph lines and horseback riders. A $100 reward would have been enough to motivate cowhands, trappers, or travelers to keep their eyes open.

These types of notices give a glimpse into how justice worked in the late 19th-century West—part formal, part folk system. Local sheriffs relied heavily on word of mouth and public cooperation. For historians, they also help trace the slow transformation of Montana from a loose collection of mining camps and ranches into an organized state with established law and order.

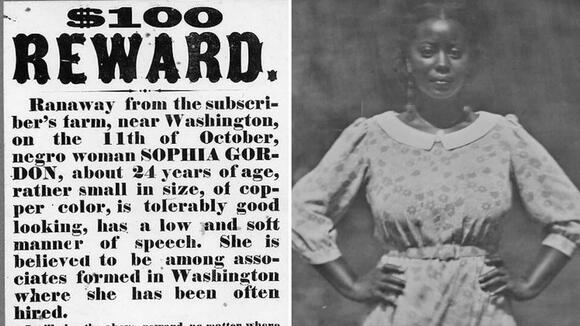

#10: $100 for locating a black woman called Sophia Gordon in 1858

Before the Civil War, countless Black women like Sophia Gordon were listed in reward notices that sought their capture and return. Such ads often stripped away their humanity, reducing them to physical descriptions and dollar amounts. Sophia’s mention in 1858—just three years before the war—appeared at a time when the debate over slavery was reaching a national breaking point.

Notices like Sophia’s remind us that each name carried a story of resistance and hope. For many enslaved women, escape was an act of both courage and survival, defying the structures that sought to control every aspect of their lives. Today, these faded papers stand as records of the individuals who refused to remain invisible in a system built on their silence.

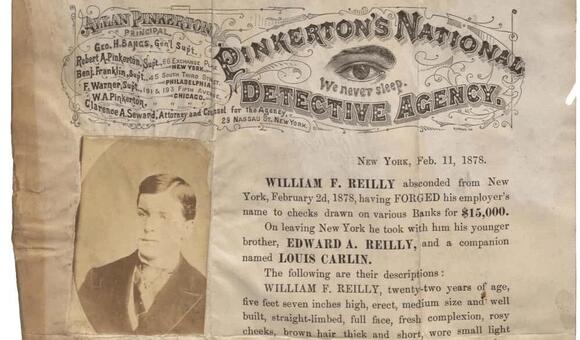

#11: Wanted poster printed by the Pinkerton National Detective Agency looking for William F. Reilly for forging his employer’s signature to draw $15,000 in 1878

The Pinkerton National Detective Agency was one of the most influential private law enforcement groups of the 19th century. Founded in 1850, it played a major role in tracking criminals across state lines before the FBI existed. By 1878, the Pinkertons had gained a reputation for their detailed investigation methods and extensive files on suspects like William F. Reilly, who forged his employer’s signature to steal a large sum of money.

The poster’s precise details reflect how professionalized the Pinkertons had become—using physical descriptions, aliases, and even handwriting samples to identify criminals. Reilly’s case demonstrated both the sophistication of late-19th-century white-collar crime and the growing reach of private detective networks that shaped modern American policing.

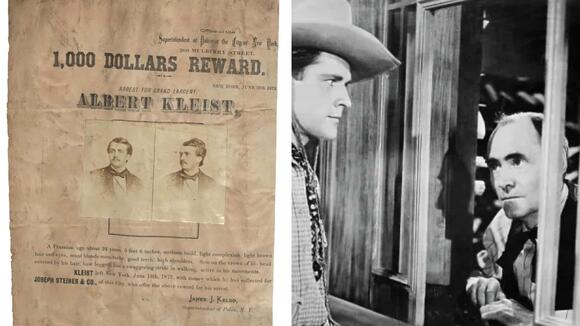

#12: $1,000 reward for the capture of Albert Kleist, who committed grand larceny (theft)

Grand larceny—major theft of money or valuables—was among the most serious property crimes of the 19th century. Albert Kleist’s case reflected the challenges of enforcing law in a nation growing too fast for its justice system to keep up. Posters like this one were crucial tools for sharing information across towns and states before centralized criminal databases existed.

The $1,000 reward signaled how seriously authorities treated the theft, an amount that would have tempted nearly anyone in the working class to assist in his capture. In many ways, these reward posters blurred the lines between law enforcement and public participation, making every passerby a potential detective.

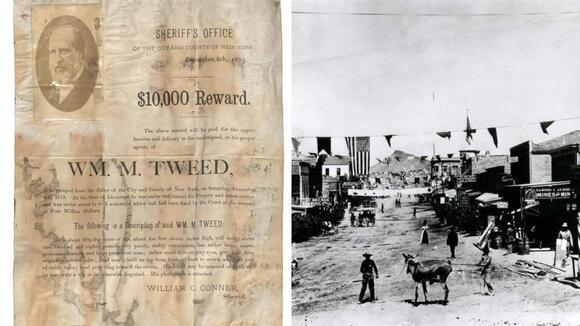

#13: $10,000 reward for capturing and delivering WM. M. Tweed, who committed forgery and other crimes, to sheriff William C. Conner in 1875

William M. “Boss” Tweed was one of the most infamous political figures in American history. As the leader of New York’s Tammany Hall political machine, Tweed built a fortune through graft, bribery, and rigged contracts. By 1875, his corruption had become national news, and his escape from jail turned him into a symbol of both greed and government reform.

The $10,000 reward for Tweed’s capture—one of the largest of the 19th century—reflected the scale of his crimes and the outrage they provoked. His eventual arrest in Spain marked one of the earliest international manhunts in American history, showing how far-reaching U.S. law enforcement efforts had become in the post–Civil War era.

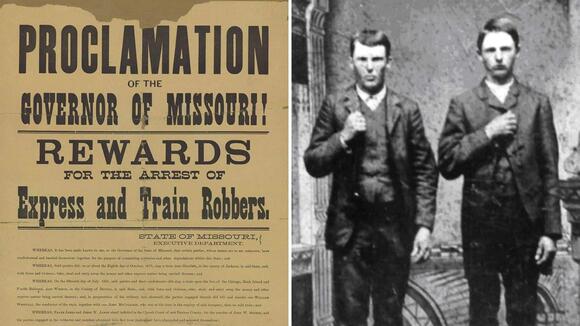

#14: 1881 wanted poster published by the Governor of Missouri for the capture of Frank James and Jesse W. James for express and train robbery

Frank and Jesse James became legendary figures in the years following the Civil War, celebrated by some as rebels and condemned by others as ruthless criminals. They led a gang responsible for robbing banks, trains, and stagecoaches across the Midwest. By 1881, the Missouri governor himself had issued this wanted poster—proof that the James brothers were seen as threats to public order at the highest level.

The James gang’s daring train robberies captured the imagination of the public, blending myth and reality. This poster stands as a testament to how the Old West was not just a story of freedom and expansion, but also of violence, celebrity, and the blurred line between hero and outlaw that defined the era’s folklore.

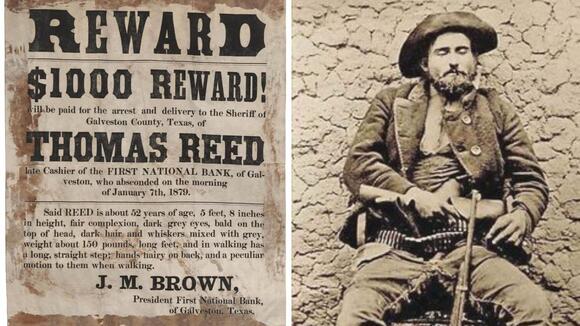

#15: $1,000 for the apprehension and delivery of Thomas Reed of Galveston County, Texas

By the late 19th century, Texas was still wrestling with its rough frontier identity—an environment where law enforcement often struggled to keep pace with rapid settlement and economic change. The wanted poster for Thomas Reed of Galveston County shows how state and local authorities relied on printed circulars to spread news of fugitives across vast distances.

The $1,000 reward reflected both the seriousness of Reed’s alleged crime and the difficulty of bringing fugitives to justice in Texas’s wide and sparsely settled counties. Posters like this illustrate the transitional moment when the frontier’s informal justice was giving way to the bureaucratic systems that would define modern American law enforcement.

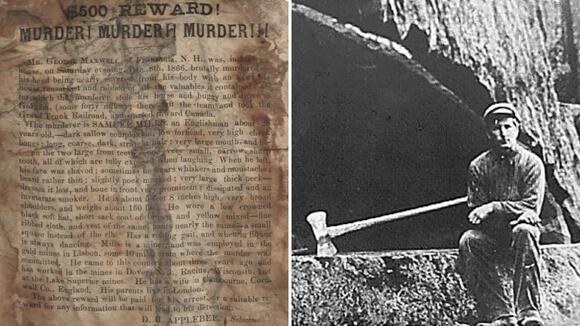

#16: $500 reward for Samuel Mills, who took the life of George Maxwell with an axe

The case of Samuel Mills was one of grim violence that shocked his community. Notices like this one were among the few ways authorities could spread word quickly before national police networks existed. The details were often blunt and unembellished, meant to grab the attention of anyone who might recognize the suspect.

In rural parts of the country, crimes committed with common tools—like an axe—were disturbingly familiar. Such posters served both as a legal notice and a public warning, reminding people of the fragility of law enforcement in remote areas.

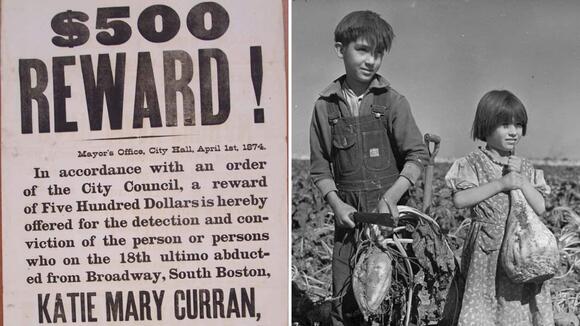

#17: A $500 offered by mayor Samuel C. Cobb for the capture of the people who kidnapped Katie Mary Curran, a 10-year-old girl

The kidnapping of young Katie Mary Curran drew public outrage and sympathy. When children went missing in the 19th century, towns often relied on mayors or private citizens to post rewards like this one to encourage leads.

Tragically, her case ended in sorrow, later linked to Jesse Pomeroy, a teenage murderer who became one of Boston’s most infamous criminals. This poster stands as a haunting glimpse into early urban crime and the desperate measures taken to find justice for victims.

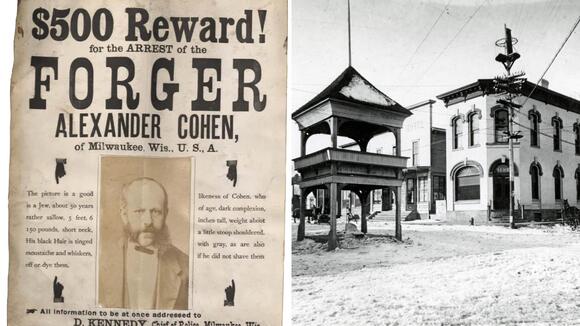

#18: $500 reward for the arrest of forger Alexander Cohen

Forgery was a serious crime in the 1800s, especially as cities grew and banking systems expanded. Alexander Cohen’s name joined a long list of con men who thrived on fake documents, checks, and false identities during a time when verifying signatures was still done by eye.

Posters like this reflected the tension between rapid financial growth and the growing pains of trust in new institutions. Forgers could disappear easily across state lines, making rewards essential to motivate informants and bounty hunters.

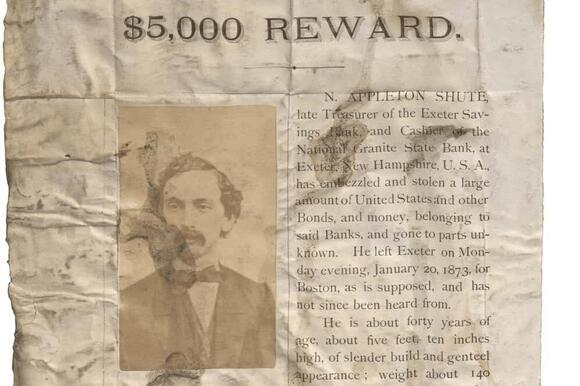

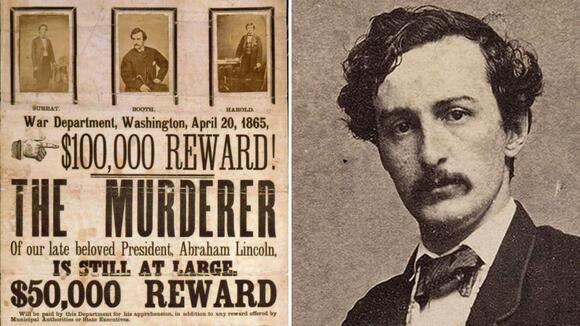

#19: $50,000 reward for the apprehension of John Wilkes Booth, the man who shot president Abraham Lincoln in 1865. There were rewards for his accomplices, too

After Lincoln’s assassination, the nation erupted in grief and fury. The U.S. government issued one of the largest rewards of its time—$50,000—for John Wilkes Booth, who had fled Washington, D.C. after the shooting at Ford’s Theatre.

The manhunt that followed was one of the most intense in American history. Booth was eventually found and killed in a Virginia barn, but his wanted poster remains one of the most recognizable artifacts from the aftermath of the Civil War.