Conscious Decisions

A Georgia man’s life was changed forever when he sustained a catastrophic brain injury. Now his family is battling the court system over what happens to his mind and body.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

At an assisted-living home, Vinit Shinde lay paralyzed in bed attempting to suck on a lollipop. One of his aides had positioned the phone so that Vinit’s brother and sister-in-law could see him. Eventually when the aide removed her hand from the stick holding the lollipop in Vinit’s mouth, he seemed to gag, trying to activate any muscles of his jaw, tongue, and throat to stop the lollipop from entering his throat or dropping out of his mouth.

In January 2018, Vinit suffered a severe and abrupt brain aneurysm at the age of 45. Multiple doctors deemed him to be in an extreme vegetative state, meaning that he did not have the typical brain function to exhibit mood or affect, cognitive functioning, executive functioning, language, or memory.

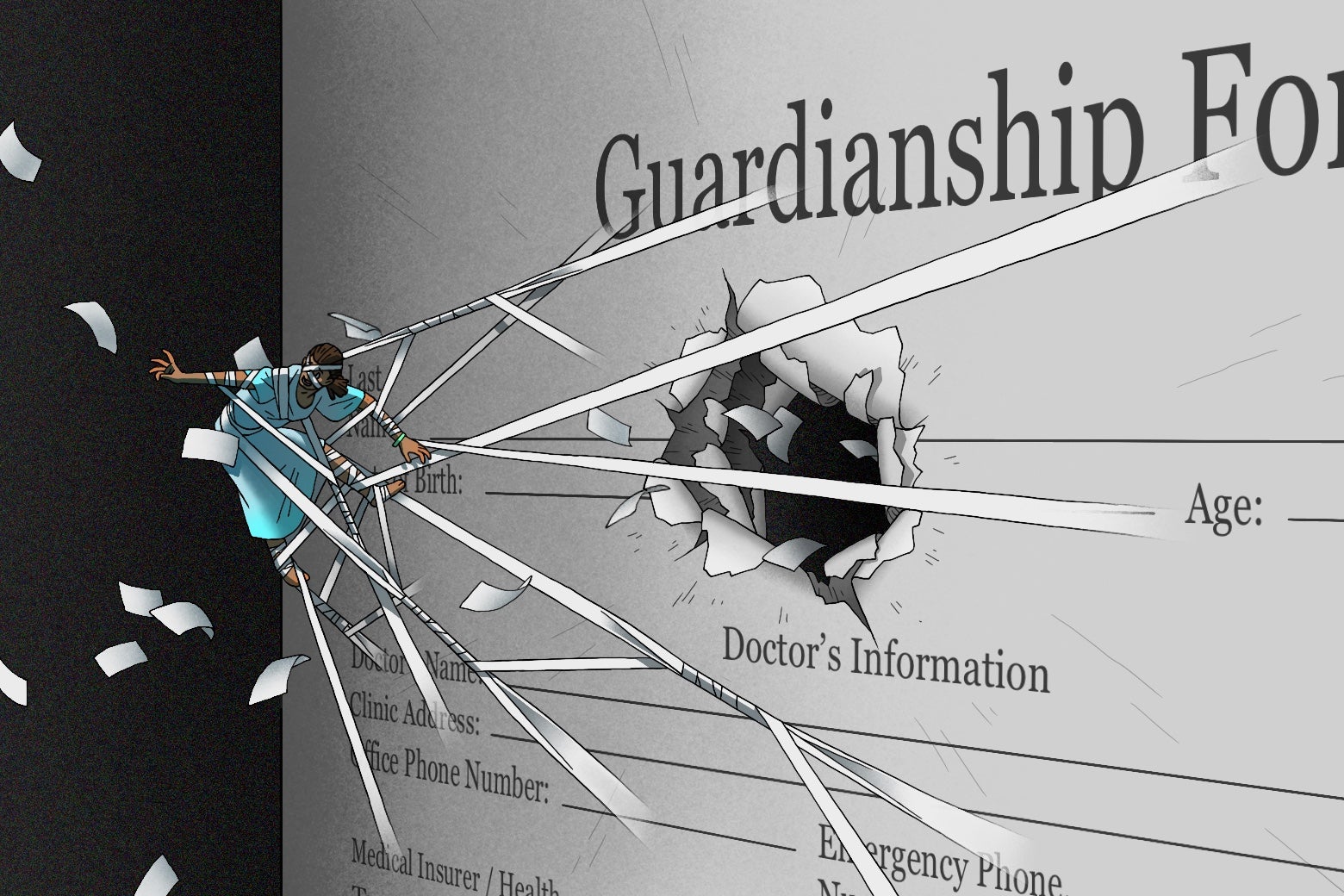

Today, Vinit is alive because of a feeding tube and full-time care–but mostly because of a decision made in Georgia’s Fulton County Probate Court, transferring guardianship of his nearly $1 million estate and future medical decisions from his brother to his ex-wife and court-appointed attorneys. Vinit is now one of an estimated 1.3 million adults in the U.S. living under guardianship, whose guardians control roughly $50 billion in assets. Across the country, these arrangements are typically under the control of an insular group of state judges and lawyers, who take on financial, legal, and medical decisions for people who may be elderly or otherwise mentally incapacitated.

Once a guardianship has been cemented and a person is officially a ward of the state, there is little recourse to change how their guardian makes financial and medical decisions for them. While they’re done with the interest of people like Vinit in mind, in practice, they can often be mired in ethical, legal, and cultural dilemmas—posing a seemingly unending string of impossible choices for the people who love and care for them.

Before the guardianship was transferred to Vinit’s ex-wife–whom he separated from in 2012 and divorced from in 2016–his family had made the difficult decision to move him into hospice. Without a will or advance directive, his only living immediate relative, his brother, had signed a Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment agreement with two doctors to transition him off of life support. After years of consulting medical professionals and believing that this would not have been a dignified life for Vinit, they proceeded with the move to hospice.

Then Vinit’s ex-wife—who would visit him from time to time—contacted the Capitol Ombudsman Program director in Atlanta to allege that he was not actually in a vegetative state but that he only appeared to be in one. In public legal filings, she claimed that Vinit could watch television and communicate with others by blinking, smiling, and laughing. (Slate has reached out to Vinit’s ex-wife and her lawyer for comment, and has not received a response.)

The ombudsman set up time to observe Vinit, after which she determined that removing his feeding tube was not in his best interests. Several nonmedical staff at the home also expressed in a letter that they were “distressed” about Vinit’s move into hospice, because “they believe [he] responds to them with smiling and that he also smiles while watching TV.”

In depositions with two of his doctors, conservatorship lawyers for his ex-wife presented the theory that there could have been a chance, however infinitesimal, that he would be satisfied in a consciousness that involved blinking his desires. She sought out to prove that not only was Vinit conscious but that his condition could be improved. Later, she filed a petition in the Fulton County Probate Court, seeking to remove Vinit’s brother as his guardian and conservator, and requesting that she be appointed the successor. With his ex-wife emboldened by the support from nonmedical experts at the home and the ombudsman, a fight over Vinit’s life and medical treatment—and the conservatorship of his nearly $1 million estate—ensued.

Even though both Vinit’s family and ex-wife may have his best interests at heart and want to make the right decisions for him, they’re still left with a set of decisions that have no right answer. What is in the best interest for someone you love who can no longer care for or make these choices for themselves? Can you let them go if there’s a chance—however slim—that they can get better? These decisions underscore the complexity behind the guardianship system at large. While this may not be the case with Vinit, the system as a whole has long come under scrutiny amid allegations of abuse, neglect, and even corruption throughout the country.

While individual family members or friends may have a myriad of desires and opinions on how to handle care for an incapacitated loved one, the financial and legal structures of the guardianship system can be ripe for evading accountability and concentrating power among one or a few stakeholders. For example, in Georgia, one 2020 investigation uncovered apparent conflicts of interest in Fulton County’s guardianship system, including a case where a court-appointed independent lawyer donated to the judge overseeing the case. In New York, a ProPublica investigation found rampant neglect and abuse, revealing that examiners tasked with care “tend to focus almost exclusively on financial paperwork” rather than the care and condition of wards. As a result, in August, the state announced a task force to overhaul the program, with some pushing for new legislation.

Other states are taking notice: Pennsylvania now requires professional guardians to pass certification exams, while Illinois lawmakers are pushing to make it harder for private guardians to profit off of vulnerable people who have no one else to look after them—after reports that a private guardianship company and law firms representing hospitals appeared to be colluding to run up costly bills at the expense of the people under guardianship.

Georgia’s policies around life and death were recently thrust into the spotlight in the case of Adriana Smith, a 30-year-old mother and nurse who was kept alive, brain-dead, as a vessel to give birth to a baby without her consent. Smith was caught in the crosshairs of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, validating a Georgia state law that considered her fetus a person if it had a heartbeat. And the public at-large became familiar with the concept of conservatorship because of Britney Spears, whose finances were tied up and controlled by her family after the system deemed her mentally unstable.

Then there’s Terri Schiavo’s case in the early 2000s. Schiavo was considered by doctors to be in a persistent vegetative state after her brain was deprived of oxygen. While her husband conveyed what he thought her wishes would be—to have life support withdrawn—her parents believed that she smiled and expressed emotion. After life support was withdrawn, autopsies confirmed that she was indeed in a “persistent vegetative state.”

More recently, there has been a rise in what legislators are calling “death with dignity” legislation. In several states, including Colorado, Maine, Montana, and Nevada, legislation has passed or is being considered to allow for people to choose physician-assisted death when they decide that life is unbearable. But in these cases, many people still have the agency and critical thinking skills to make that decision for themselves.

For example, one man in Maine chose physician-assisted death last November after a long battle in ALS. His wife—now an advocate for others to do the same—reported that he had lost the ability to speak and swallow, and that his claustrophobia made him feel like he was “drowning and suffocating” at the same time. Opponents or those with more nuanced approaches to “death with dignity” believe that lines should be drawn around depression or certain disabilities—that choosing death while depressed is more about abandonment than autonomy.

But what about people like Vinit, who could never have predicted a sudden brain bleed rendering him with no autonomy? Who gets to choose for them? Both Vinit’s family and his ex-wife may want the best for him—but even they can’t know what exactly he would choose if he could right now. It’s a case that’s emblematic of the core problem: These are impossible decisions, and there’s no “right” choice with an impossible decision.

Several years ago, Vinit was barely spending time in bed unless he was sleeping. With no kids or pets and recently divorced, he had very few grounding commitments beyond his job as an IT architect and a condo he owned in Atlanta. According to friends and family, Vinit was a gregarious person who liked to explore the world and had many friends. His ex-girlfriend Sarah told Slate that he “knew no stranger,” was “witty and funny,” and “everyone’s best friend.” One of his best friends told Slate over text that “Vinit was vibrant, highly intelligent, popular, and positive. Simply put, he was a pleasure to be around.” His brother described him as a “kind, generous and very social person.”

On Jan. 27, 2018, Vinit’s 45th birthday, he didn’t show up to work. Two days later, his employer alerted his family. His family also had wondered if something was wrong, as they hadn’t heard from him on his birthday either. Vinit’s best friend, his best friend’s wife, and his ex-wife went to check on him at his apartment. He was discovered by his best friend collapsed on the floor, awake but incoherent.

Doctors found that he had suffered a subarachnoid hemorrhage resulting from a ruptured brain aneurysm. While they were able to coil the rupture and keep his heart beating, he was extremely impaired—unable to swallow, communicate, move his body, or control his bowel movements.

Vinit’s brother recalls a neurosurgeon at the time saying that Vinit’s brain was so damaged that the most he could ever do was “move his neck from one place to another, or utter a few words,” he told Slate. In November 2018, around nine months after the aneurysm, another neurologist echoed this analysis, telling the family that Vinit did not qualify for any treatment options or experimental treatments because there was no improvement in his condition.

Yet Vinit’s family felt he was too young to let go. They moved him to a brain injury rehabilitation center, but doctors there also concluded that his brain condition was irreversible. It was around this time that Vinit’s brother was appointed his conservator and guardian in Georgia. He was moved to a nursing home, where physicians initially urged the deescalation of life-sustaining care due to his negative prognosis and poor quality of life. Vinit’s family was paying out of pocket for his treatment, and they also crowdfunded among friends and family to pay for some of his rising medical costs, hoping that some progress could be made to improve his cognitive functioning and quality of life.

But two years after the aneurysm, Vinit was not showing any signs of cognitive improvement. In a deposition, one of his doctors said he was technically “demented,” but that his cognition was far worse than someone who has dementia. A medical social worker also acknowledged that Vinit was on a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube through which all medication and nutrition were administered, and that he had “no awareness of his surroundings and no purposeful movements.” A note reviewed from his care center to a Georgia ombudsman referred to him as “essentially brain-dead.”

His brother told Slate that he imagined that the Vinit who was single, enjoying his local bars, drinking beer, and traveling the world would not have wanted to live in a bed covered in sores, unable to communicate, and without the ability to feed, clothe, or bathe himself unless fully assisted.

He also reflected upon a conversation that the brothers had in 2017 at their mother’s funeral, where they agreed that neither brother would want a long or painful death like that of their father, who died of a prolonged battle with cancer.

While difficult to accept, Vinit’s brother and two doctors—the attending physician at his home and the medical director of the hospice—signed the POLST agreement, recommending discontinuation of care and designating the three of them as the people who would make the end-of-life decisions on his behalf.

In January 2021, Vinit was referred to hospice, which the ethics committee of the health care facility had no objections to. It was a heart-wrenching decision for the family, but in a final letter written to Vinit’s attending physician at the assisted-living home, his family wrote: “[We] would talk to [Vinit] about settling down with a family and buying a house. However, that was not his plan. He wanted to live freely on his own terms.”

What further complicates this answer about what is right or wrong for Vinit is that researchers are giving pause to the idea that all people in vegetative states have no consciousness—or that all people who become nonverbal and paralyzed would rather choose death. These factors are large parts of the reason why Vinit’s family and his ex-wife may try all options—no matter how small the chance of success—of keeping him alive.

In August 2024, neurologists published a study into the potential for consciousness among vegetative or minimally conscious patients. They found that 25 percent of the patients studied, who were asked to spend several minutes completing cognitive tasks like imagining themselves playing tennis or swimming, responded with the same patterns of brain activity seen in people with healthy brains.

Following the 2024 study that found potential consciousness in certain vegetative patients, it was noted in the New York Times that “it is possible that people with disorders of consciousness may one day take advantage of brain implants that have been developed to help people with other conditions to communicate.”

But since many of these vegetative states are brought about by a sudden event like an aneurysm—meaning many previously healthy people may not have had time to prepare a will or directive—the question of what they would have wanted can be a tricky one to decipher. What also complicates who lives or dies is the court systems, and the many people involved in a family member’s life or death who might have competing interests—many of which might be valid and well-intentioned, depending on the perspective.

At the end of the day, the decision for Vinit’s guardianship came down to money. A judge ruled that Vinit’s brother had not received the proper court approval to sell about $20,000 of Vinit’s stock in order to pay for certain bills piling up—and that he should have sold their deceased mother’s home in India instead.

In a Fulton County Probate Court presentation reviewed by Slate—called “Playing God: The Ethical Conflicts in End-of-Life Decisions”—Vinit’s story is used as a case study to demonstrate the need for the court to intervene and keep him alive. They even use Bollywood actors in one of the slides about Vinit.

While the Georgia probate court likely does not have jurisdiction over a family home in India, the court was still able to claim that Vinit’s brother was not acting as a proper fiduciary in the stock sale. As a result, he was removed as guardian and conservator. Vinit’s ex-wife was appointed as guardian to oversee his medical affairs, while a county conservator was appointed to oversee his finances.

His brother appealed the decision, but the court-appointed attorney for Vinit agreed with the court’s decision to strip him of his guardianship over his brother. The attorney’s statement to the Georgia Court of Appeals said that fiduciary considerations were more important than the POLST agreement or end-of-life considerations.

Today, Vinit’s family FaceTimes him weekly from Boston to see his face, and they travel from their home in Boston to Atlanta when they can. He seems vacant and incomprehensible to them.

But now, the family feels mostly in the dark about Vinit’s current and future medical plans. Medical records reviewed by Slate show that Vinit has been in and out of Emory University Hospital over the past few years since his ex-wife became guardian. One document from 2023 states that his insurance did not cover “post-transplant immunosuppressive drugs when [he] got this service.” The family does not know what “this service” refers to, but Vinit’s family and friends have observed an increasing amount of “blinking” in their recent interactions with Vinit—as well as the blurting of unrelated words and letters.

This ambiguity is obviously frustrating to his family. Vinit’s sister-in-law describes the perpetuation of his life, especially if his bodily autonomy is indeed being transferred to his ex-wife’s decision-making, as “cruel.” His brother adds: “As Vinit’s only living relative, I have not been consulted or informed about ongoing medical treatment, raising serious ethical concerns. Why are we excluded from medical decisions about his care?”

In April 2023, the Shinde family received an amicus brief in support of their case from end-of-life care nonprofit Compassion & Choices, which wrote that: The “court’s primary focus should be on uncovering what the incapacitated person would have wanted and that the process followed by the Georgia probate court in this case did not allow for that to happen.” A spokesperson for Compassion & Choices shared with Slate that they “weighed in with the amicus brief to ensure that the court was prioritizing what Mr. Shinde would have wanted when determining what treatment decisions were or were not appropriate.”

With various medical advancements over the years that allow for brain injury patients like Vinit to be kept alive in care homes, the decision about whether to withdraw life support and care—or not—can feel unthinkable. There are open medical and scientific questions around the presence of covert consciousness—and ethical and sometimes religious questions around whether someone’s body should remain preserved, even if the person who they once were feels all but gone. Then, there’s the optimism around future medical developments for brain injury patients, the notion that there is even the slightest chance that someone could improve, especially when their faces may exhibit expressions we classify with consciousness, like smiling. Although there may be no meaning behind those reflexes in patients with severe brain injuries, the presence of those seemingly human expressions may make it even more difficult to let someone go.

Beyond Vinit and his brother’s conversation at their mother’s funeral, there is no documented information about whether he would have desired to be kept alive in such a condition. (Vinit’s ex-wife and lawyers did not respond to Slate’s request for comment.) Sarah, the ex-girlfriend who perhaps knew him most intimately closest to his aneurysm, told Slate she never spoke to him about whether he would want to stay alive in a vegetative state. But she did say that “I 100 percent think that he would not want to be sitting in a bed for seven years.”

When asked about the family’s decision, Sarah said: “I would have supported their decision. There are two avenues of thought: First, I don’t think anyone should live this way, he wouldn’t want that. But it’s also not my decision. It’s the family’s.”

Get the best of news and politics

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.