Have you ever wondered what makes your body tick away like a clock counting down the hours? Death seems inevitable, something we all share but rarely understand deeply. You’re about to explore the biological machinery that determines your lifespan and eventually stops your heart from beating. The science behind mortality isn’t as straightforward as you might think.

Your cells are constantly battling against time, fighting damage, and trying to maintain the complex systems that keep you alive. Yet despite these remarkable defensive mechanisms, every organism faces an expiration date. The question is: why? What actually goes wrong in the microscopic world inside your body?

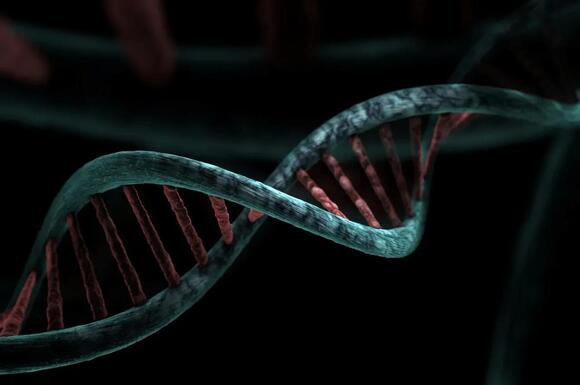

Your Cellular Clock Runs Out

Think of your cells as tiny time bombs with built-in countdown timers. Each human cell can only divide around 50 times before it stops, a phenomenon scientists call the Hayflick limit. What’s controlling this biological countdown? Your telomeres.

These protective caps at the ends of your chromosomes shrink with every cell division, and once they reach a critical size, cells stop dividing and eventually die. It’s like the plastic tips on shoelaces gradually wearing away until the lace frays apart. This isn’t just some abstract cellular quirk. Telomere shortening drives cellular senescence and aging, and accelerated telomere dysfunction precipitates several conditions associated with normal aging.

Here’s where it gets interesting: stress, poor diet, and chronic inflammation can speed up telomere shortening. Studies show that people with stressful lives, including African-American men experiencing racism, have shorter telomeres than average. On the flip side, roughly about a tenth longer telomeres have been observed in people adopting healthier lifestyles with moderate exercise and plant-based diets.

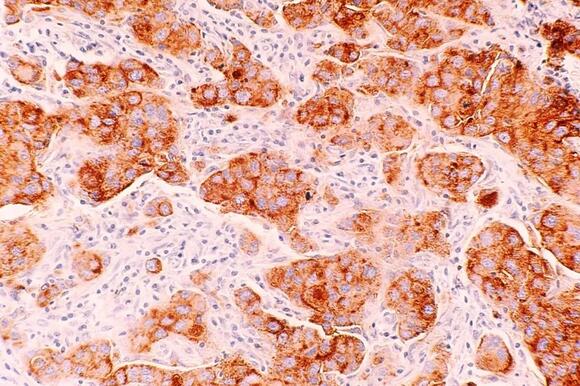

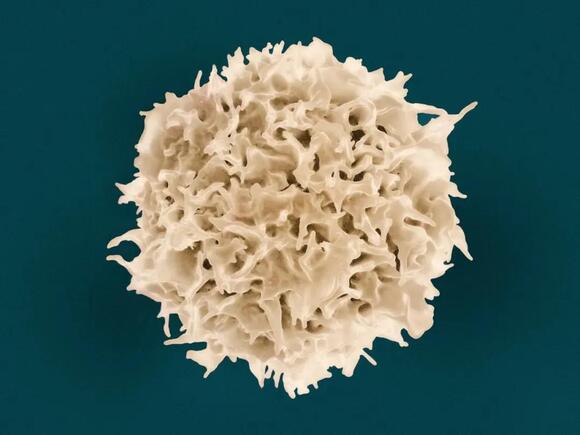

When Cells Refuse to Die

If cells are no longer needed, they commit suicide by activating an internal death program called apoptosis, or programmed cell death. Sounds dramatic? It absolutely is. In developing nervous systems, up to half of nerve cells die soon after formation, and billions of cells die every hour in the bone marrow and intestine of healthy adults.

This controlled death is actually vital for your survival. Without it, damaged cells would accumulate, potentially turning cancerous. Apoptosis plays a role in preventing cancer, and when it’s prevented, it can lead to uncontrolled cell division and tumor development. Your body is constantly making life-or-death decisions at the cellular level.

Once cells reach a critical point in the destruction pathway, they cannot turn back – the protease cascade is destructive, self-amplifying, and irreversible. When apoptosis goes haywire, you face serious problems. Too much cell death contributes to neurodegenerative diseases, while too little allows cancer to flourish.

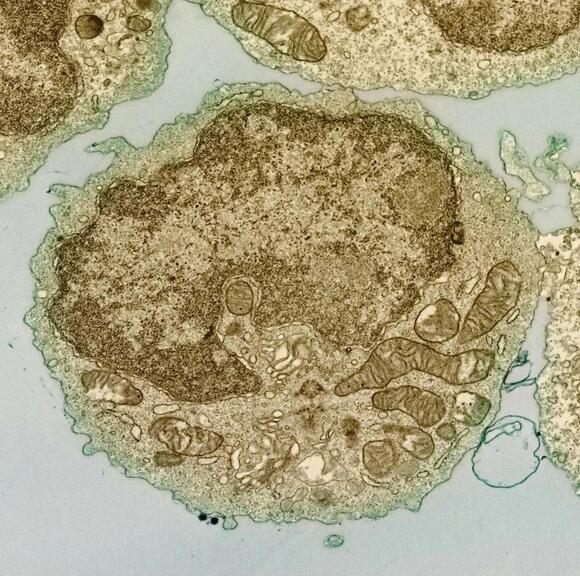

The Powerhouse Starts Failing

Mitochondrial dysfunction has emerged as one of the key hallmarks of aging and is linked to metabolic syndrome, neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. These tiny organelles inside your cells are essentially energy factories converting food into usable power.

As you age, these factories start breaking down. Mitochondrial dysfunction manifests as impaired energy production, increased oxidative damage, decline in quality control, and changes in structure and dynamics. Picture a power plant with aging equipment – it produces less energy while spewing more toxic byproducts.

Aging mitochondria lose their ability to provide cellular energy and release reactive oxygen species that harm cells. These reactive molecules are like molecular shrapnel, damaging everything they touch. Increased mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production contributes to genomic instability, telomere attrition, and epigenetic alterations, creating a vicious cycle of cellular decay.

Your DNA Takes a Beating

Every day, DNA accumulates damage from oxidation and other sources, but your cells have elaborate repair systems constantly patching things up. Studies comparing DNA repair capacity in different mammalian species show that repair ability correlates with lifespan. Species with better DNA repair mechanisms simply live longer.

When DNA repair fails, the consequences are severe. Mouse models of DNA repair syndromes reveal a striking correlation between the degree to which specific repair pathways are compromised and the severity of accelerated aging. It’s hard to overstate how crucial this system is – your genome is under constant attack from both internal metabolism and external factors.

DNA damage to the somatic genome is identified as a major cause of aging, compromising essential cellular functions like transcription and replication, leading to cellular senescence, apoptosis, and mutations. Imagine trying to read a book where random letters keep disappearing or changing. Eventually, the instructions become unreadable, and cells malfunction.

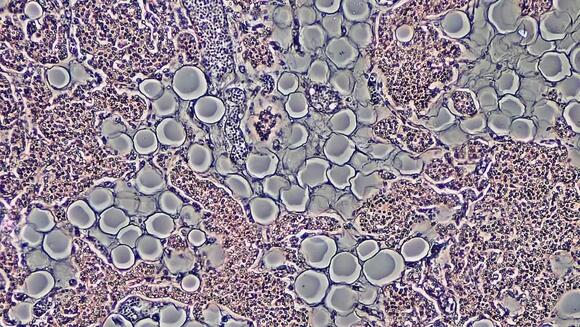

Senescent Cells Poison Their Neighbors

Senescent cells accumulate with age and in age-related diseases, and are associated with loss of tissue function during aging. These are essentially zombie cells – not quite dead but no longer functioning properly. They stop dividing but refuse to die, lingering in your tissues like unwelcome houseguests.

The real problem? Overaccumulation of senescent cells promotes accelerated biological aging and age-related diseases, possibly due to an aged immune system that inefficiently eliminates them or an incompetent inflammatory response they release. These cells secrete inflammatory molecules that damage surrounding healthy cells.

Studies show that if senescent cells are selectively eliminated from tissues, this can alleviate a multitude of age-related pathologies, suggesting senescent cells play a causal role during aging. Scientists are now developing drugs specifically targeting these zombie cells, with some already in human clinical trials for age-related diseases.

The Inevitable Accumulation Theory

Theories hold that the body ages because wear and tear accumulates in tissues over years – waste products build up in cells, backup systems fail, repair mechanisms break down, and the body simply wears out like an old car. This damage theory makes intuitive sense. Like any complex machine running continuously for decades, parts eventually fail.

Aging derives from deterioration of cellular activity and ruination of regular functioning, with cells naturally sentenced to stable and long-term loss of living capacities despite continuing metabolic reactions. Your cells are constantly trying to maintain themselves, but the second law of thermodynamics eventually wins – entropy increases, disorder accumulates.

Some researchers propose programmed aging instead. The second group of theories suggests aging is driven by genes – an internal molecular clock set to a particular timetable for each species, supported by animal studies showing altered single genes can increase lifespan. Perhaps your body has a genetic program instructing it when to decline, a biological suicide switch.

Why Some Escape Death’s Grip

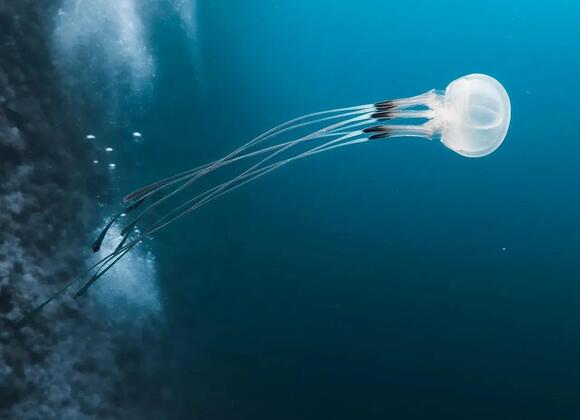

Some organisms show biological immortality, like Hydra and the jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii, and organisms showing only asexual reproduction, such as bacteria and some protists, are immortal to some extent. These creatures challenge our understanding of inevitable mortality.

Single-celled organisms don’t age as we do – amoebas and bacteria split into daughter cells without deteriorating and never lose the ability to proliferate, whereas human cells can only divide about 50 times before dying. What makes multicellular life so vulnerable? Complexity, it seems, comes with a price.

Evolution selected traits that benefit early survival and reproduction even if they contribute to earlier death – a genetic effect called antagonistic pleiotropy, where genes enable reproduction when young but cost the organism life expectancy in old age. Your body essentially prioritizes passing on genes over long-term survival. Once you’ve reproduced, evolution stops caring about your longevity.

The Maximum Human Lifespan Mystery

Humans have seen significant increases in life expectancy over 200 years but not in overall lifespan – nobody on record has lived past 122 years. Despite medical advances extending average lifespan, the maximum remains stubbornly fixed.

Researchers debate the potential maximum human lifespan, with some believing 115 is the top while others think the first person to live to 150 has already been born, though roughly around 120 years appears to be the current natural limit. The number of centenarians has increased in recent decades, but people living past 110 hasn’t increased proportionally, suggesting biological limits.

Of roughly 150,000 people who die each day globally, about two-thirds die from age-related causes. The largest unifying cause of death in developed countries is biological aging leading to complications known as aging-associated diseases, which cause loss of homeostasis triggering cardiac arrest and irreversible deterioration of the brain and tissues. Eventually, accumulated damage overwhelms your body’s ability to compensate.

What Does This Mean for You

You now understand that dying isn’t caused by a single mechanism but by multiple interconnected processes slowly degrading your cellular machinery. Your telomeres shorten, mitochondria fail, DNA damage accumulates, cells become senescent, and repair systems decline. These processes feed into each other, creating cascading failures throughout your body.

The interplay between mitochondrial dysfunction and other hallmarks of aging highlights the complex and interconnected nature of the aging process, and understanding these reciprocal relationships is crucial for developing interventions that target multiple hallmarks to mitigate age-related decline. Science is beginning to untangle this web of decay.

The good news? Researchers are actively exploring interventions targeting these aging mechanisms – from drugs that eliminate senescent cells to compounds supporting mitochondrial function and DNA repair. While we haven’t conquered death, we’re starting to understand its biological roots. The question now isn’t just , but whether we can slow the inevitable march toward it. What would you do with an extra decade of healthy life?