Wendy Red Star

Wendy Red Star

Satirical artist Wendy Red Star is debunking myths and upending clichés about First Nation and Native people. As two exhibitions feature her work, she tells the BBC how she uses "humour as a bridge".

What's wrong with this picture? That may well be a viewer's first response to Wendy Red Star's mind-bending photograph, Winter, on display in the opening gallery of Winter Count: Embracing the Cold, at Ottawa's National Gallery of Canada (NGC). But take another look and you may begin to understand what's actually right about it.

The exhibition juxtaposes works by First Nation artists with those of Canadian settlers, British and European artists from the 19th to 21st Centuries as a way to both celebrate and contemplate the experience of the season from multiple cultural perspectives. In keeping with that theme, the differing ways in which each group perceives and misperceives – as well as sees and doesn't really see – the others is what Red Star is asking us to reflect on in this work.

Born in Billings Montana in 1981 and an enrolled member of the Apsáalooke (Crow) tribe, Red Star places herself at the centre of her photographic tableau, dressed in the brightly hued traditional tribal attire, which she sewed herself. Featuring elk teeth and beads characteristic of Crow dress, her clothing is historically authentic. But Red Star's forlorn stare compels us to do a double take as we peer at the landscape that surrounds her.

Winter wonderland

What viewers may at first have assumed would be a panoramic First Nations-themed winter wonderland, on second glance proves instead to be a mordant satire of the clichés of Indigenous life in tune with nature that have become embedded in the Western mind.

In this landscape, the unnatural has replaced the natural. Those are white plastic packing chips, not snowflakes, covering the ground and decoratively dotting the artificial ferns and trees. The pristinely white and perfectly rounded snowball Red Star holds in her hand is a synthetic orb resembling the weightless toy balls used to play catch with toddlers. Fabrications, too, are the spookily wide-eyed owl, ink-black ravens, redder-than-red cardinals, and the death-omen of an ox skull strategically scattered throughout the scene. And the backdrop itself is an illusion – not the great outdoors, but a photomural.

People are so indoctrinated into thinking about the history of Native people in a certain way that if you just present the actual facts, they think this is challenging – Wendy Red Star

Red Star's sendup is playful, even kitsch. As she said to Aperture, "I was watching a lot of John Waters' movies" at the time she produced the series. She created The Four Seasons photo series – comprising a different photographic panorama for each season – when she was in her mid-20s and living for the first time away from Montana, earning her MFA in sculpture at UCLA in Los Angeles.

John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation

John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation

As she walked through the Native galleries of the Los Angeles Museum of Natural History, she felt "super weird," she tells the BBC. "I was seeing people view Crow material, moccasins I think," assuming "that this is the past and there aren't Crow people walking around… This is a weird fantasy dynamic being portrayed here," she thought. "People walk in here thinking they are going to learn the true history" of First Nations, and yet "this does not align with my sense of it".

The BBC reached out to the LA Museum of Natural History about their representation of First Nation people but they did not comment. The museum is now showing a permanent exhibition, LA Reimagined. According to its website, "visitors will discover the ways Native people have shaped Los Angeles, past and present, when they see newly commissioned portraits of Native Americans living in Los Angeles County as well as a video in which community leaders share what it means to be an Indigenous Californian living in LA today."

Red Star is not fond of the word "challenging" to describe her works. "People are so indoctrinated into thinking about the history of Native people in a certain way that if you just present the actual facts, they think this is challenging! Because that's not what the institutions have been putting out there."

Having taken with her to LA her traditional Crow regalia, Red Star proceeded to create tableaux that upend assumptions. Instead, she says, her work asks viewers to recognise the absurdity in the disparities between the stereotypes presented and the actual history and culture of Indigenous people. The Four Seasons series, she says, "allows people to comment on that absurdity." The purpose is not to shame but to "enlighten," and "the laughter is part of the recognition – oh, how silly of institutions to have put this forward!"

Myth of the 'Vanishing Indian'

Unmasking such clichés is as integral to Red Star's artistic vision as is her use of "humour as a bridge" to do so, says Wahsontiio Cross, a co-curator of the exhibition and NGC's Associate Curator, Indigenous Ways and Decolonisation. Red Star's work talks back to the dioramas seen in natural history museums that often depict cultural habitats – including those of Indigenous peoples – and treat these communities as if they were specimens for historical or anthropological study. They also critique the work of the US photographer Edward S Curtis (1868-1952), best known for his documentary portrayals of American Indians – including members of Red Star's Crow Nation – in the 1900s.

Wendy Red Star/ Image courtesy of artist and Sargent's Daughters

Wendy Red Star/ Image courtesy of artist and Sargent's Daughters

Curtis saw his mission as "documenting what he thought of as 'a dying race'," Cross tells the BBC. He cropped out from his photos "signs of modernity" such as clocks, she says, serving the illusion that Indigenous people remain stopped in time, living only in the past. In perpetuating the myth of the "Vanishing Indian", she says, Curtis erased the "reality" that Indigenous people "have adapted to new technologies throughout time".

By wearing her tribal regalia, Red Star is saying, 'We're here, we're not going anywhere' – Wahsontiio Cross

In contrast, by making herself the main subject in each of her photographic seasons, Red Crow is asserting the continuing survival and presence of all Indigenous people, says Cross. "By wearing her tribal regalia, she is saying, 'We're here, we're not going anywhere. And what she wears is not a costume, not a stereotype, it is part of a history that connects to her ancestors and her culture and will continue to do so into the future."

Still, Red Star regards Curtis and his relationship to Native people as complex. "His ability to photograph the different communities came through his interpreters, who were themselves tribal members... From my community he had Alexander Upshaw... So, when I look at Curtis's photos now," she says, she thinks about Upshaw.

For Red Star, satire is a tool. Her multimedia works synthesise photography, collage, sculpture and historical artifacts. They appear in the collections of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art, among other institutions, and in 2024 she was awarded the MacArthur Fellowship.

False assumptions

In addition to Winter Count, her work is now being featured in an exhibition at the Trout Gallery at the Art Museum of Dickinson College, Wendy Red Star: Her Dreams Are True. Curator Shannon Egan describes Red Star as "an archivist, activist and artist," adding that "she is a prodigious researcher of both the historical record and of popular culture, and puts all these aspects together".

The theme of the first work in the Trout Gallery show is similar to that of Winter. Called The Last Thanks, Red Star described it with the stinging tagline, "On the first Thanksgiving was our last supper". Here we see Red Star, dressed in the same attire as in her Four Seasons series, seated at a long dining table. She spreads her hands in grace to bless a meal not of plenty but of borderline poverty – American bologna, canned green beans, processed cheese slices and sliced white bread. Plastic skeletons bedecked with headdresses made of paper cut-outs are posed on each side of her, with their arms gesturing "hear no evil, see no evil, say no evil". The piece is at once a parody of Leonardo Da Vinci's The Last Supper and a sassy debunking of the US myth of the origins of the Thanksgiving holiday as a jointly held celebration by Pilgrim settlers and Indigenous Americans.

Wendy Red Star / Image courtesy of artist and Sargent's Daughters

Wendy Red Star / Image courtesy of artist and Sargent's Daughters

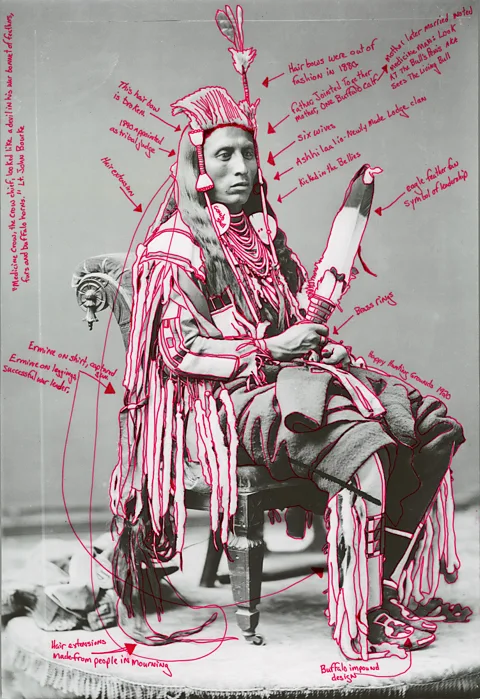

In her other works, including those on display at the Trout, Red Star highlights details about many unnamed individuals in historic photos like those of Curtis. She has annotated in red ink reproductions of historic photos to identify the tribal significance of each piece of clothing and jewellery worn by the people in that image. She has also created collages featuring images of museum objects in order to demonstrate the roles they played – and still play – in communal life and in tribal celebrations.

More like this:

• The Indigenous American supermodel bringing change

Many of these works – such as Winter and The Last Thanks – are filled with bright colours, Red Star's vivid palette reflecting the vibrant hues and brilliant patterns that characterise her community's clothing and jewellery. Their vivacity can seem the opposite of the subdued black and white or sepia-toned photographs of the past. But Red Star points out, if colour photography had been available to Curtis and others, they would have captured a similar range of colours. "It would be amazing to see those in colour," she comments. "I know it would change how people would view those images."

In the meantime, Red Star's satirical upending of clichés about First Nation people continues to help viewers recognise and counter false assumptions about the past, figuring out what's fact, and what's fiction.

Winter Count: Embracing the Cold is at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, until 22 March 2026

Wendy Red Star: Her Dreams are True is at the Trout Gallery, the Art Museum of Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA, until 7 February 2026

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.