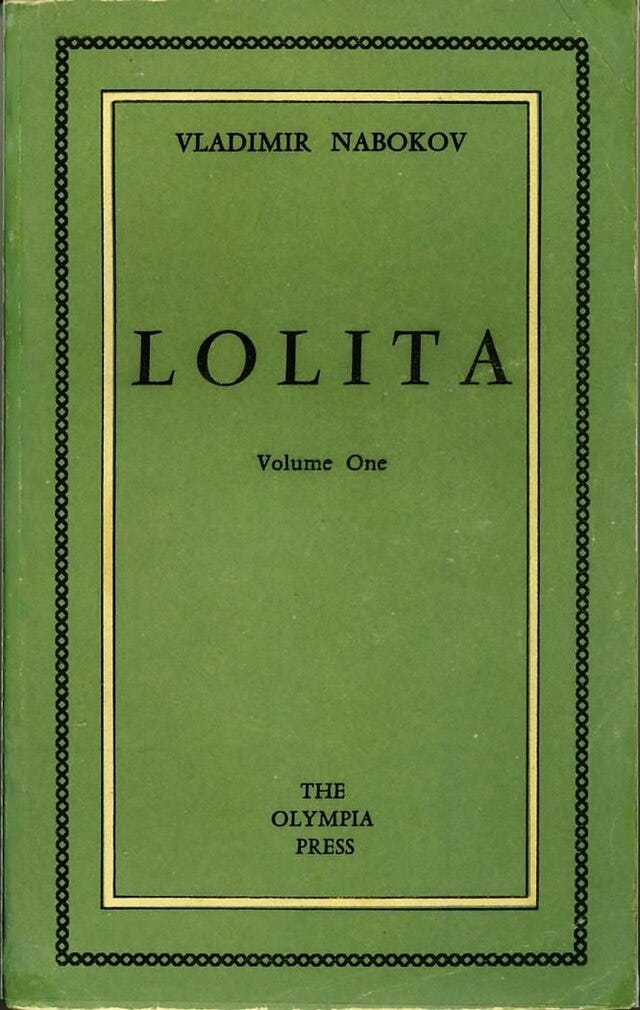

Alongside his other hobbies, Jeffrey Epstein read for fun. The latest batch of his emails, released on January 30 by the Justice Department, display the syntax of a liberal arts undergrad who has taken too much Adderall, but document his taste thoroughly. We already knew about Epstein’s appreciation of Nabokov and Lolita; his correspondence reveals myriad men and women trying to ingratiate themselves through their readings of the Russian master (including journalist Edward Jay Epstein, Yale computer scientist David Gelernter, Princeton biologist Corina Tarnita, and then-Harvard English professor Elisa New). Epstein also enjoyed French literature: he admired Proust and Jean-Paul Sartre, recommended Anne Desclos’s Sodom novel Story of O, and wrote enthusiastically about Simone de Beauvoir, whom he described as Sartre’s brilliant “girlfriend,” spelling her name both “simone de beauoirs” and “simone de bauvoi.” Writing to the Crown Princess of Norway, Epstein dismissed Gavin Bowd’s translation of Michel Houellebecq’s The Possibility of an Island as “awful.”

Within the English-language tradition, Epstein might have read Joyce’s Ulysses — he and mathematician David Berlinski seem to have debated the relative merits of Joyce and Nabokov in Paris over dinner. In one message, Epstein borrows the title of the Irish novel to refer to a complicated accounting scheme that is harder to follow than “Oxen of the Sun.” But then again, maybe he just watched the movie (the subject line of an email informing him of a “Ulysses” delivery is “DVDs”). He received verses from T.S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding” from Deepak Chopra and, in an unexpectedly sincere exchange, a redacted sender with characteristically Epsteinian punctuation quoted Yeats to an unknown addressee: “When you are old and gray;How many loved your moments of glad grace And loved your beauty with love false or true,But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you…….”

Epstein understood that these highbrow references would aid him in his quest to establish himself in elite circles, perhaps one of the last domains in which literature still confers prestige. It is tempting to try to decode what else his selections might reveal: did he esteem Borges (“great,, literature,, poems,, impossible translations”) because “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” and its world conspiracy of intellectuals spoke to him? Or was it Borges’s interest in pop philosophy and science that Epstein was keen to?

Like so much else in his life, Epstein’s literary exploration was typically subordinated to his relentless network-building. He was given a translation of Clarice Lispector by Noam Chomsky’s Brazilian wife, recommended Thomas Bernhard’s The Woodcutters; and bought V.S. Naipaul’s Collected Short Fiction on Amazon a day after Berlinski mentioned him. One of his main literary correspondents seems to have been the publicist Peggy Siegal, who once invited him to a dinner with Jonathan Franzen and Salman Rushdie and tried to get Nora Ephron and Philip Roth to attend another.

One of the few personal interests that comes across in the files is Jewish history and identity. Epstein recommended Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint to former Obama White House counsel Kathryn Ruemmler as well as Leon Uris’s anti-Palestinian propagandistic epic The Haj. Woody Allen’s almost-stepdaughter-turned-wife Soon-Yi Previn thanked Epstein profusely after her daughter signed up for a Bard seminar on Isaac Babel and the Russian Revolution. He mentioned the Bible frequently in his correspondence with Chopra, Chomsky, and Ghislaine Maxwell, who urged him to take scripture classes with her (“What should you do?” Ghislaine wrote, “Miss me... Then there is always that Talmud meeting I think I mentioned once before”).

Epstein did seem to feel that all of his reading gave him a more profound and insightful spirit. Much has been said about literature’s capacity to improve our moral sensibilities, but Epstein seems to point, on the contrary, to literature’s ability to corrupt us or justify our corruption. Identifying himself with the Bard, he once wrote: “I understand, shakespeare understood, competing loyalties.. follow you highest principle. truth, really, and do it sooner rather than later. it will not endear you, but will garner respect.” In the end, he was less of a King Henry and more of an Iago.

Julia Kornberg is the author of Berlin Atomized and The Parties.