Since the mid-1970s, Mimi Plumb has chronicled man’s destructive relationship with nature, specifically in California. In her black-and-white photographs of the Golden State—whether depicting parched lake beds, a Texaco gas station submerged in the Salton Sea, or crowds gazing at conflagrations—Plumb cultivates a sense of doom and dreamlike un-reality, channeling the feeling of California as a place where, as Joan Didion wrote, “a boom mentality and a sense of Chekhovian loss meet in uneasy suspension.”

This February, the High Museum of Art, in Atlanta, will open the first museum survey dedicated to Plumb’s work, with around one hundred photographs created between 1972 and 2025 revealing the photographer’s clear-eyed vision of California’s unsettling sublime. The show’s curator, Gregory J. Harris, discovered Plumb via her first book, Landfall (2018), which features images made between 1984 and 1990. The book’s tone is established by a bare-bones text by Plumb: “I remember having insomnia for a time when I was nine years old. My mother said there might be a nuclear war.” After having a visceral reaction to Plumb’s sun-bleached landscapes and enigmatic portraits, Harris got to know the artist personally in 2021 at a portfolio review in Montana. “How on earth did all of this amazing work get made, and yet it’s hardly ever been shown?” Harris remembers thinking. “It seemed like a crazy omission to me.”

Plumb’s images burn with prescience. Crises that were just beginning to percolate when she made the Landfall pictures—a rightward shift in politics, extreme weather events—now saturate daily life. “Mimi’s work is not about climate change, per se, but it is about the experience of what it’s like to live in an unstable world,” said Harris. “Her photographs are united by a sensibility about the anxiety of the world spinning off its axis and falling apart.”

Plumb spent her youth hiding from the blazing sun in Walnut Creek, then a rapidly developing East Bay suburb. In the mid-1970s, while studying photography at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), she returned home to create a self-portrait of the alienation and boredom she felt coming of age in an inhospitable suburban environment. “I was always interested in what was going on outside of my world, but I always related back to how I felt about it,” Plumb said of her early pictures, which were later collected in her book The White Sky (2020). “It was very personal in that way, but it usually wasn’t about specifically looking at myself.”

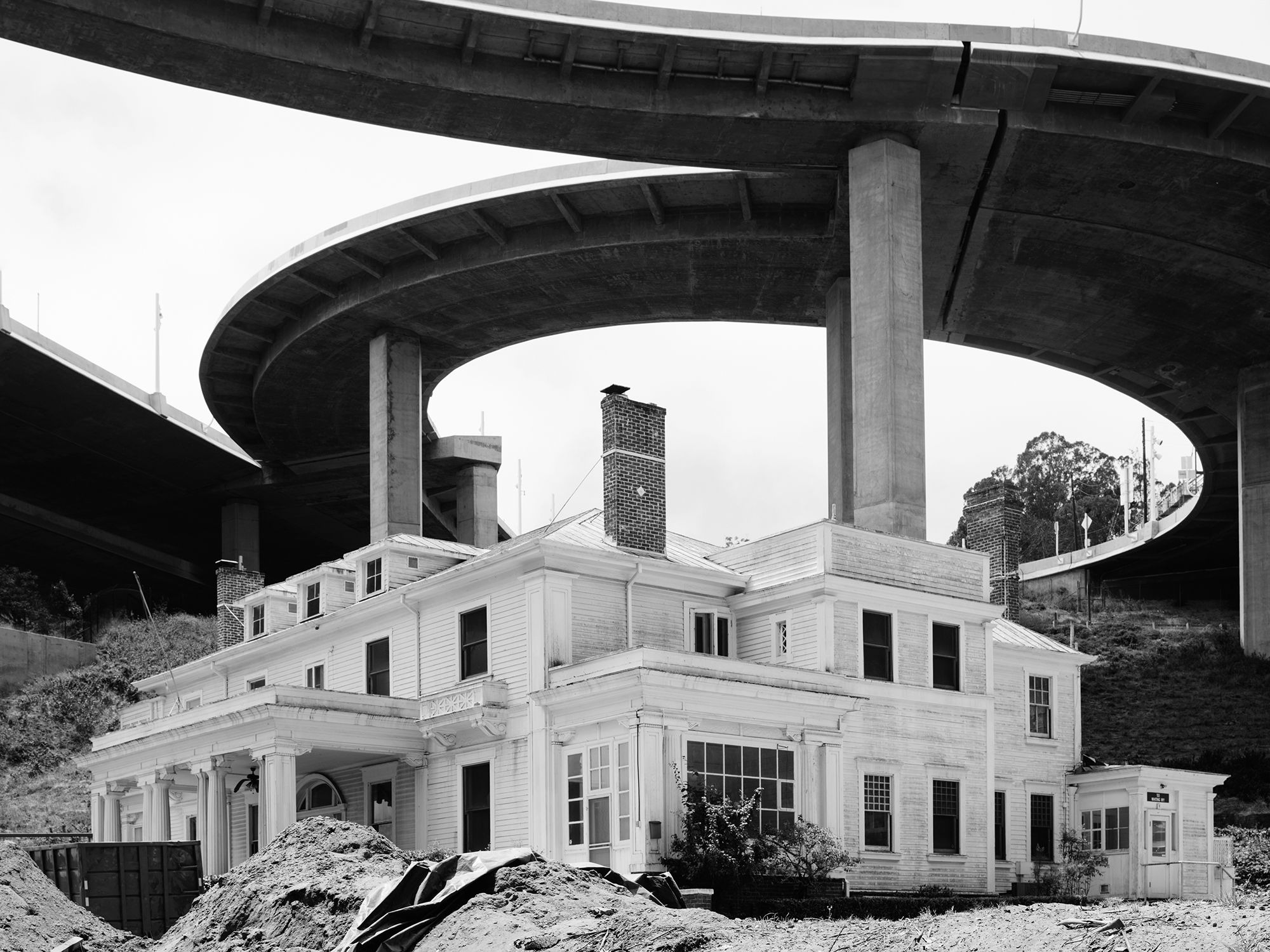

Plumb’s pictures of San Francisco from the ’80s and ’90s suggest the decay of the American dream.

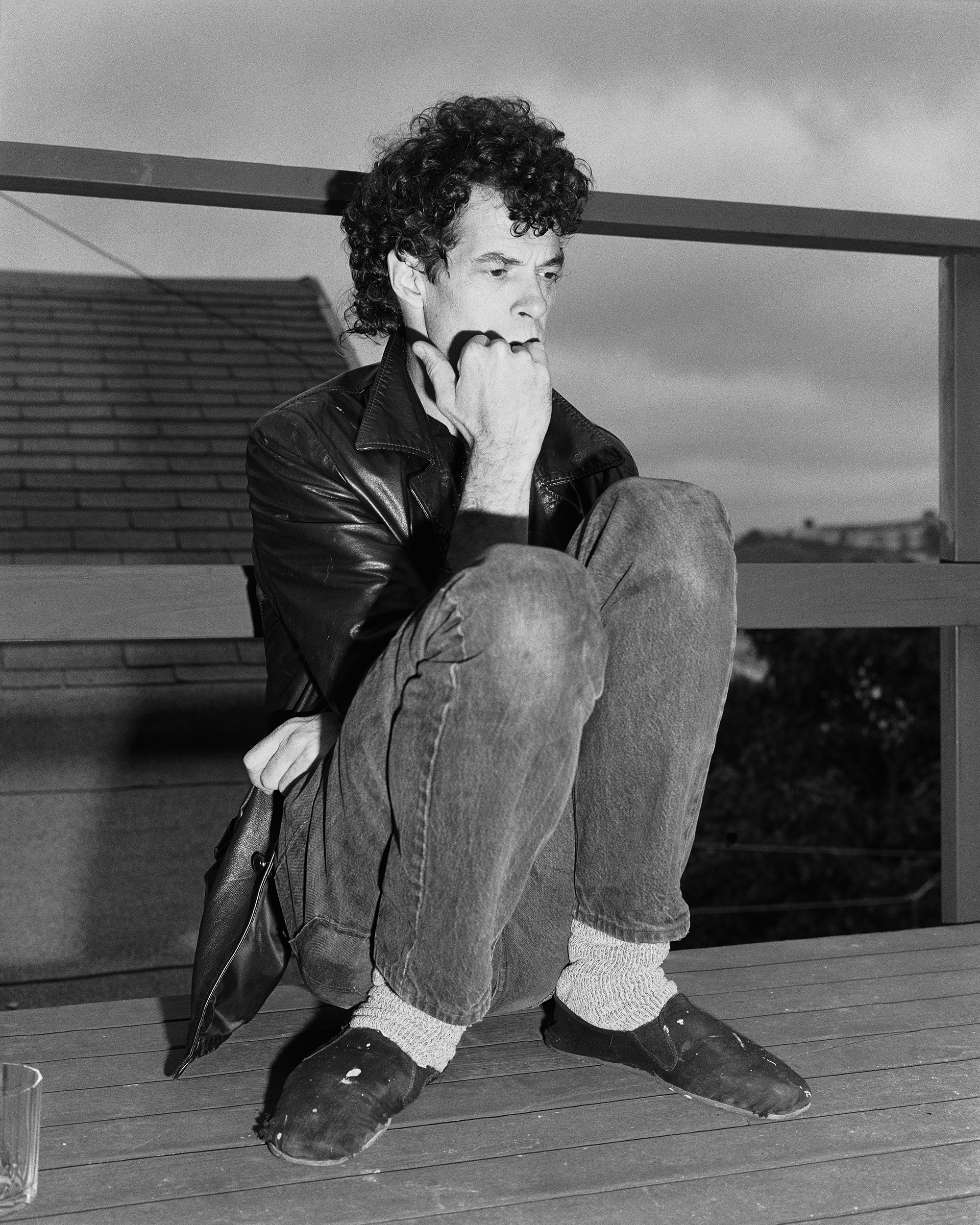

By the early 1980s, Plumb’s fragile optimism had curdled into dismay thanks to Reagan, Chernobyl, and the cultural and social contagion of capitalism: “The feeling that we could really change the world that I felt back in the ’60s and early ’70s had definitely faded.” Plumb returned to SFAI for graduate school, intent on photographing her environment and investigating how power is used and abused. “My teacher Larry Sultan thought that the work needed to get hotter, meaning that all this anxiety that I was feeling wasn’t showing up in the pictures. So I started combining the landscape pictures with images of my friends,” she explained.

Unlike the more detached New Topographics photographers, Plumb portrays the communities left to contend with these “man-altered” environs. She also began using flash, amplifying a feeling of tension and anxiety. Take Tang (1987), which features a girl at a bowling alley. By photographing the figure from behind, as she often does, Plumb evokes the German Romantic Rückenfigur, the flash illuminating every strand of her subject’s nearly floor-length hair. She appears to be hesitating at the edge of a void; a slight push, and she would tumble forward into the unknown.

Made primarily with a 6-by-7-inch medium-format camera, Plumb’s pictures of San Francisco from the ’80s and ’90s suggest the decay of the American dream. Here, California’s cloudless skies are obscured by telephone wires and mountains of industrial waste. An image of Grant Wood’s iconic American Gothic inexplicably hanging in a desolate lot is an uncanny slice of strangeness. A square of white picket fencing clings to a scrubby hillside as if suburbia itself is an invasive species. A colonial revival mansion shrinks to a dollhouse beneath a Treasure Island freeway, the sharp facade looking amazingly inflexible compared to the promise of the looping cement overhead. While her images may be “grounded in the language of documentary photography and realism, they’re not documentary projects,” Harris noted. “They’re much more ambient, creating an experience or a sense of something rather than telling a concrete story.”

All photographs courtesy the artist

The High Museum show includes selections from Plumb’s most recent series, Reservoir (2021–25), for which she received a 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship. Her austere photographs of cracked lake beds and silent skies depict the effects of a mega-drought and are, in their own quiet way, Plumb’s most explicitly political work. Traveling to the Receding Lake II (2022) shows people trudging across a parched expanse, a plastic inflatable their only shade from the oppressive sun.

Is this impulse to seek pleasure and relief in nature even in the face of climate disaster a heartening affirmation of resiliency or a symptom of miserable indifference? Plumb doesn’t look away. As Robert Adams once observed, “All that is clear is the perfection of what we were given, the unworthiness of our response, and the certainty, in view of our current deprivation, that we are judged.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 261, “The Craft Issue,” under the column Backstory.