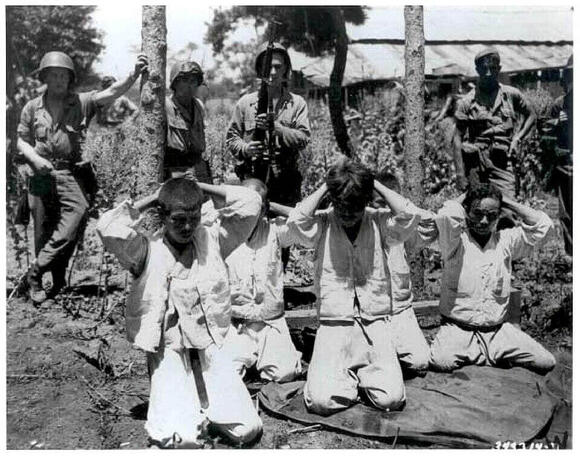

Around noon on July 26, 1950, several hundred South Korean villagers sat on a railroad embankment near the hamlet of No Gun Ri. American soldiers had ordered them there, searched their belongings, and promised safe passage south. Then the soldiers left.

Planes suddenly strafed the crowd of men, women, and children. The survivors scrambled for cover beneath a concrete railroad bridge as soldiers opened fire from nearby positions. What followed became one of the deadliest acts committed by U.S. troops against civilians in the 20th century.

For the next three days, soldiers of the 7th Cavalry Regiment poured rifle and machine gun fire into the twin tunnels. Entire families huddled behind walls of corpses. Mothers shielded their children with their bodies. The survivors drank blood-mixed water from a stream running through the underpass.

"Children were screaming in fear and adults were praying for their lives, and the whole time they never stopped shooting," said Park Sun-yong, who lost her 4-year-old son and 2-year-old daughter in the carnage.

Disaster on the Korean Peninsula

The massacre occurred only a month into the Korean War. North Korean forces had invaded the South on June 25, 1950, catching American troops completely unprepared. Task Force Smith, the first U.S. unit to engage the enemy, was overrun on July 5. The 24th Infantry Division lost its commander, Major General William Dean, as a prisoner of war at Taejon on July 20.

The 7th Cavalry Regiment landed at Pohang-dong on July 18 as part of the 1st Cavalry Division. This was Custer's old regiment, the Garryowens, infamous for the disaster at Little Bighorn 74 years earlier. The troops had been enjoying occupation duty in Japan. Half the regiment's sergeants had recently transferred to other units. Many soldiers were teenagers with no combat experience.

The retreating Americans they encountered made a terrifying impression on the new arrivals as they moved to the front.

Fears of North Korean infiltration spread rapidly. Intelligence reports indicated enemy soldiers were disguising themselves as refugees to slip behind American lines. An estimated 380,000 South Korean civilians were fleeing south in those chaotic first weeks, streaming through non-established front lines.

American commanders responded with drastic measures. On July 24, a communication logged at the 8th Cavalry Regiment headquarters stated that refugees were not to cross the front line. Those trying to cross were to be fired upon. The order added a caveat to "use discretion in case of women and children."

Major General William Kean of the 25th Infantry Division likewise ordered that "all civilians seen in this area are to be considered as enemy and action taken accordingly."

Major General Hobart Gay, commanding the 1st Cavalry Division, told reporters he believed most civilians moving toward American lines were North Korean guerrillas. He would later describe refugees as "fair game." On August 4, after the No Gun Ri killings, Gay ordered the Waegwan bridge over the Naktong River blown while hundreds of fleeing Koreans were still crossing.

The Road to No Gun Ri

The villagers who died at the railroad bridge came primarily from Chu Gok Ri and surrounding hamlets in Yongdong County, roughly 100 miles southeast of Seoul. On July 23, American soldiers and a Korean policeman arrived and ordered them to evacuate. The area would soon become a battlefield.

Most residents fled to Im Ke Ri, a mountain village about two kilometers away. They believed they would be safe there.

On the evening of July 25, American soldiers appeared at Im Ke Ri. They ordered the villagers to gather their belongings and promised to escort them to safety near Pusan. Between 500 and 600 people set out on foot, leading ox carts loaded with possessions, some with children strapped to their backs.

The column spent one night at Ha Ga Ri. The next morning, they continued toward No Gun Ri.

When the refugees reached the railroad crossing around midday on July 26, American soldiers stopped them. The troops ordered everyone onto the tracks and searched their belongings. They found no weapons or proof that any of them were guerillas.

Then, without warning, the soldiers departed. Several aircraft appeared moments later and strafed the civilians.

Three Days of Killing

The air attack killed dozens immediately. Some survivors estimated that roughly 100 people died on the railroad embankment before anyone could reach shelter.

"Chaos broke out among the refugees. We ran around wildly trying to get away," recalled Yang Hae-chan, who was 10 years old at the time.

The survivors fled into a small culvert beneath the tracks.

Suddenly, American ground fire drove them from there into a larger double tunnel under a concrete railroad bridge. Each underpass measured approximately 80 feet long, 22 feet wide, and 40 feet high.

The 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment had dug into positions on a ridge overlooking No Gun Ri. The unit was in poor shape. On the night of July 25, the troops had panicked and scattered during a disorganized retreat from their forward positions near Yongdong. More than 100 men went missing before the battalion was reorganized the next morning.

Communications specialists Larry Levine and James Crume later said they remembered hearing orders to fire on the refugees coming from a higher level, probably from 1st Cavalry Division headquarters.

A mortar round landed among the refugees. Then came what Levine called a "frenzy" of small-arms fire.

Machine gunner Norman Tinkler of H Company said he fired roughly 1,000 rounds into the tunnels. He saw "a lot of women and children" among the white-clad figures on the railroad tracks.

"We just annihilated them," Tinkler said.

Joseph Jackman of G Company told the BBC that his commander ran down the line shouting orders to fire. "Kids, there was kids out there, it didn't matter what it was, 8 to 80, blind, crippled or crazy, they shot 'em all," Jackman said.

"It was assumed there were enemy in these people," said ex-rifleman Herman Patterson, explaining the mindset. He further added it was a massacre.

Thomas Hacha of the nearby 1st Battalion watched the killing unfold. "I could see the tracers spinning around inside the tunnel," he recalled. "They were dying down there. I could hear the people screaming."

Not everyone participated. First Lieutenant Robert Carroll, a 25-year-old reconnaissance officer with H Company, said he stopped some of the sporadic shooting. When a young child running down the tracks was hit, Carroll carried the wounded child back to the tunnel where the battalion surgeon was treating refugees injured by the firing.

I